This is one of the four memorial sites for the victims of the Mountain Meadows Massacre. See this page for more information.

In September 1874, a federal grand jury indicted nine Mormon militiamen for crimes related to the siege and massacre. Some of those men immediately went into hiding as fugitives from justice. About 50 other militiamen were involved in the massacre, along with an unknown number of Paiute Indians. Only one, John D. Lee, was brought to trail and convicted.

On March 23, 1877, almost 20 years after the massacre, federal officials took Lee to the scene of the crimes. Not far from this very spot, he was executed by firing squad. He was buried about 120 miles from here.

Ever Remembered

In honor of those who rest in this field. They were innocent and died in unjust attacks that began on September 7, 1857. They were defending their friends and families, who buried them before leaving the protection of their camp.

To the other victims of the Mountain Meadows Massacre who lie in unknown graves, rest in peace, and be assured you are remembered.

In Memory of Milam Lafayette Rush

Echoes of a distant past can be heard throughout these meadows.

The sounds of innocent victims which will never be forgotten.

Each life was more than just a name inscribed on a monument,

They were living family members, friends and neighbors.

The story of their lives should be recorded, shared and cherished.

And, we must share these stories of our forefathers that will forever last.

Not only for our ancestors passed of long ago, but for all our descendants to come.

For, we cannot live our future without looking at our past.

Every joy and sorrow, every triumph and loss bears witness to their struggles.

These lives will never be lived in vain: they will forever live in our hearts.

By: Billy Hightower, descendant of Milam Lafayette Rush.

Memorials

1859

The original monument at this site was established by the U.S. Army. It consisted of a stone cairn topped with a cedar cross and a small granite marker set against the north side of the cairn and dated 20 May 1859. Military officials marked some other burial sites in the valley with simple stone cairns.

1932

The Utah Trails and Landmarks Association built a protective stone wall around the 1859 grave site in September 1932. The association president was George Albert Smith of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles and later President of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

1936

The Arkansas Centennial Commission and Arkansas History Commission placed a cast iron historical marker on Highway 7 about three miles south of Harrison, Arkansas. The marker, near the William Beller home and what is now known as Milum Spring, identifies the area as the departure place for some members of the caravan.

1955

On 4 September 1955, the Richard Fancher Society of America unveiled a granite memorial to the victims in a park at Harrison, Arkansas.

1990

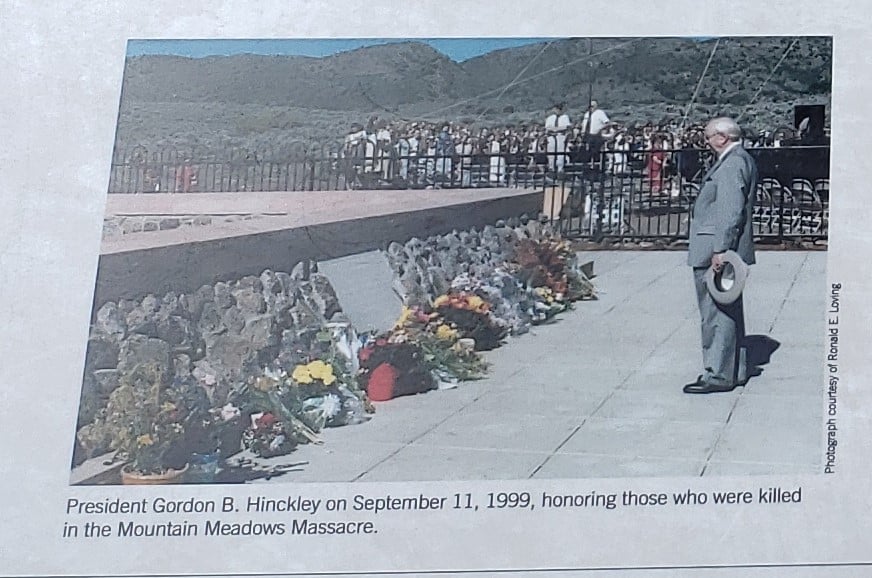

The State of Utah, families of the victims, and local citizens erected the Mountain Meadows Memorial on a nearby hill. The granite marker lists the known victims and surviving children. President Gordon B. Hinckley of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints dedicated the memorial on 14 September 1990 during a meeting in Cedar City.

1999

Under the direction of President Gordon B. Hinckley and with the cooperation of the Mountain Meadows Association and others, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints replaced the 1932 wall and installed the present Grave Site Memorial. President Hinckley dedicated the memorial on 11 September 1999.

Siege, Murder, and Burials at the Emigrants’ Campsite

Members of the Arkansas wagon train set up camp at this site on Saturday, September 5, 1857. On Sunday they likely rested and gathered for a Christian worship service – a pattern they had followed throughout their journey.

The next morning they were attached without warning. They pulled their wagons into a circle slightly larger than the fenced area where you are now. They chained the wagon wheels together and dug below each wheel to lower the wagon beds to the ground. This provided a shield against gunfire. They also dug a long defensive trench that served as a rifle pit. About 140 men, women, and children tried to take cover in the wagon circle, with many huddling together in the trench.

At least seven emigrants were killed here in the first attack. The emigrants repulsed the attackers, killing one and wounding two. Three or more other emigrants died here during the five-day siege that followed.

Each time firing resumed on the camp, the women and children could be heard screaming with fear. And with each attack, the emigrants put up a brave and determined defense. Not all the defenders were men. Survivor Milum Tackitt told of his aunt Eloah Angeline Tackitt Jones valiantly joining the fight, grabbing a gun that had belonged to one of the fallen men.

Throughout the siege, the emigrants were cut off from their water supply. Courageous men ran from the wagon circle to get water at the nearby spring. Despite heavy gunfire, some managed to fill their buckets and return to the circle. Two men once left to gather firewood, finished their task under gunfire, and returned unharmed.

Others bravely left the wagon circle. Stories about these men differ. Some accounts say that three or four young men left the safety of the camp and went northeast. They were most likely going to Cedar City to seek help. Only one of those young men made it back to the campsite alive. Another account tells of three other men, one of them with the last name Baker, escaping during the siege. They headed southwest, carrying a document that described the emigrants and what they had endured. All three were tracked down and murdered in the desert. The document they carried has disappeared.

On the fifth day of the siege, attackers came to the camp. Under a white flag, they deceived the emigrants with a false promise of safe passage to Cedar City. The emigrants were almost out of ammunition. They needed water. The wounded required attention. Realizing that they could not endure much more, they surrendered. Grieving , they rapped their dead in buffalo robes, buried them reverently, and walked away from the campsite. The men were the last to leave, relying on their captors’ promise to protect them and their families.

Gravesite Memorial

This rock cairn is patterned after one that was built in May 1859, almost two years after the Mountain Meadows Massacre. The original was 50 feet around and 12 feet high. It was topped by a cedar cross extending another 12 feet high.

Soldiers in the United States Army erected the original cairn to mark the place where they had buried bones of 34 members of the Arkansas wagon train. They used a trench – dug by wagon train members during the attack – as the mass grave. They also buried bones in at least two other mass graves in the valley.

Other the next several decades, the original memorial was damaged by vandalism, floods, and erosion. In September 1932, the Utah Trails and Landmarks Association built a stone wall around the site.

In 1999, after years of neglect, the memorial received renewed attention. Volunteers from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints prepared the site for the memorial that stands here today. The current memorial contains stones from the original cairn.

In the process of constructing the current memorial, workers found bones of 29 persons. Those bones were reinterred in a crypt, now marked by an engraved granite paver inside the northeast corner of the stone wall surrounding the cairn. Relatives of the victims wrapped the bones in beautiful hand-woven shrouds and encased them in oak ossuaries. The ossuaries were respectfullu placed on a thin layer of Arkansas soil.

On September 9, 2017, relatives of the victims buried a child’s skull that had been removed from the site by U.S. Army personnel.

Statements from the Leaders of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

Statement of Dedication, President Gordon B. Hinckley, September 11, 1999

“We intend to maintain the memorial and keep it attractive….

“… We have a Christian duty to honor, to respect, and to do all feasible to recognize and remember those who died here. May this cairn stand as a sacred monument to honor all of those who fell, wherever they might have been buried in these Mountain Meadows….

“May the peace of heaven rest upon this hallowed ground and may no evil hand do damage of any kind. May all who visit here do so in a spirit of reverence and respect for the honored dead.”

Statement of Regret, Elder Henry B. Eyring, September 11, 2007

“The gospel of Jesus Christ that we espouse abhors the cold blooded killing of men, women and children. Indeed, it advocates peace and forgiveness. What was done here long ago by members of our Church represents a terrible and inexcusable departure from Christian teaching and conduct. We cannot change what happened, but we can remember and honor those who were killed here.

“We express profound regret for the massacre carried out in this valley 150 years ago today and for the undue and untold suffering experienced by the victims then and by their relatives to the present time.

“A separate expression of regret is owed to the Paiute people who have unjustly borne for too long the principal blame for what occurred during the massacre. Although the extent of the involvement is disputed, it is believed they would not have participated without the direction and stimulus provided by local Church leaders and members….

“May the God of Heaven, whose sons and daughters we all are, bless us to honor those who died here by extending to one another the pure love and spirit of forgiveness which His Only Begotten Son personified. “