The Great Salt Desert

The Hastings Cutoff to the California Trail continues approximately 60 to 80 miles northwest from Hastings Pass toward Grayback Mountain, the Great Salt Lake Desert, the Silver Island Mountains, and Pilot Peak. Named in 1845 by John C. Fremont, Pilot Peak served as a valuable landmark for guiding wagon trains across the desert. The first water and grass after crossing the desert are at the base of the peak.

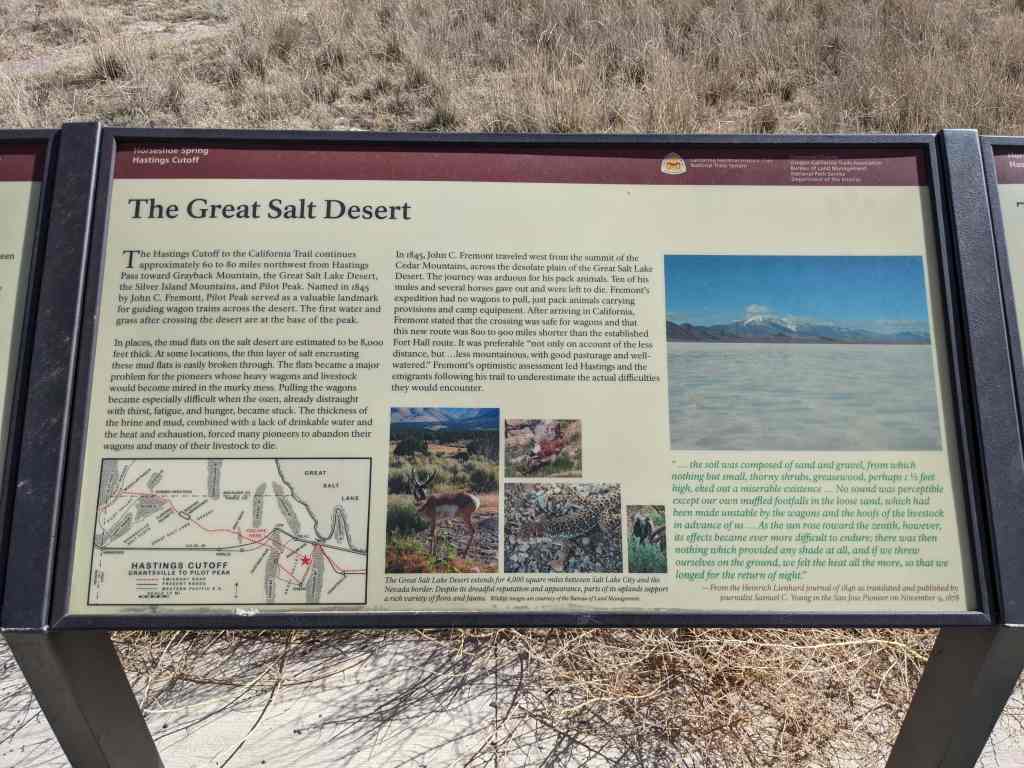

In places, the mud flats on the salt desert are estimated to be 8,000 feet thick. At some locations, the thin layer of salt encrusting these mud flats is easily broken through. The flats became a major problem for the pioneers whose heavy wagons and livestock would become mired in the murky mess. Pulling the wagons became especially difficult when the oxen, already distraught with thirst, fatigue, and hunger, became stuck. The thickness of the brine and mud, combined with a lack of drinkable water and the heat and exhaustion, forced many pioneers to abandon their wagons and many of their livestock to die.

In 1845, John C. Fremont traveled west from the summit of the Cedar Mountains, across the desolate plain of the Great Salt Lake Desert. The journey was arduous for his pack animals. Ten of his mules and several horses gave out and were left to die. Fremont’s expedition had no wagons to pull, just pack animals carrying provisions and camp equipment. After arriving in California, Fremont stated that the crossing was safe for wagons and that this new route was 800 to 900 miles shorter than the established Fort Hall route. It was preferable “not only on account of the less distance, but…less mountainous, with good pasturage and well- watered.” Fremont’s optimistic assessment led Hastings and the emigrants following his trail to underestimate the actual difficulties they would encounter.

“… the soil was composed of sand and gravel, from which nothing but small, thorny shrubs, greasewood, perhaps 1/2 feet high, eked out a miserable existence… No sound was perceptible except our own muffled footfalls in the loose sand, which had been made unstable by the wagons and the hoofs of the livestock in advance of us… As the sun rose toward the zenith, however, its effects became ever more difficult to endure; there was then nothing which provided any shade at all, and if we threw ourselves on the ground, we felt the heat all the more, so that we longed for the return of night.”

-From the Heinrich Lienhard journal of 1846 as translated and published by journalist Samuel C. Young in the San Jose Pioneer on November 9, 1878

Located at Horseshoe Springs in Tooele County.