Central Utah Relocation Center (Topaz Internment Camp) has been designated a National Historic Landmark.

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066. Without any judicial hearings and due process of law, more than 120,000 persons of Japanese ancestry were forcibly uprooted from their homes and taken under armed guard for relocation and detention in a system of assembly centers and internment camps.

Over 8,100 Japanese Americans were confined here at Topaz, including Fred Korematsu and Mitsuye Endo, whose involvement in Landmark U.S. Supreme Court cases challenged the constitutionality of the exclusion and relocation. In December 1944 the court held that “admittedly loyal” citizens could not be deprived of their liberty and held in relocation centers.

This site possesses National significance in illustrating the history of the United States of America.

Over 120,000 Japanese-Americans, two thirds of whom are U.S. Citizens, are uprooted from their west coast homes and incarcerated by their own government. It is 1942, wartime hysteria is at a peak. They are imprisoned in ten inland concentration camps where they remain behind barbed wire, under suspicion and armed guards for up to 3 1/2 years. Topaz is one of the ten camps.

Without hearings or trials, this act of injustice is based solely on the color of their skin and the country of their origin. America’s fear and distrust of these citizens – precipitated by Japan’s attack upon Pearl Harbor – is placated.

Lost within this rush to judgement is the denial of constitutional rights, major losses of personal property and the labelling of its own citizens as enemy. Ironically, through this mass incarceration is spearheaded by thoughts of disloyalty, not a single case of espionage against the U.S. is ever discovered.

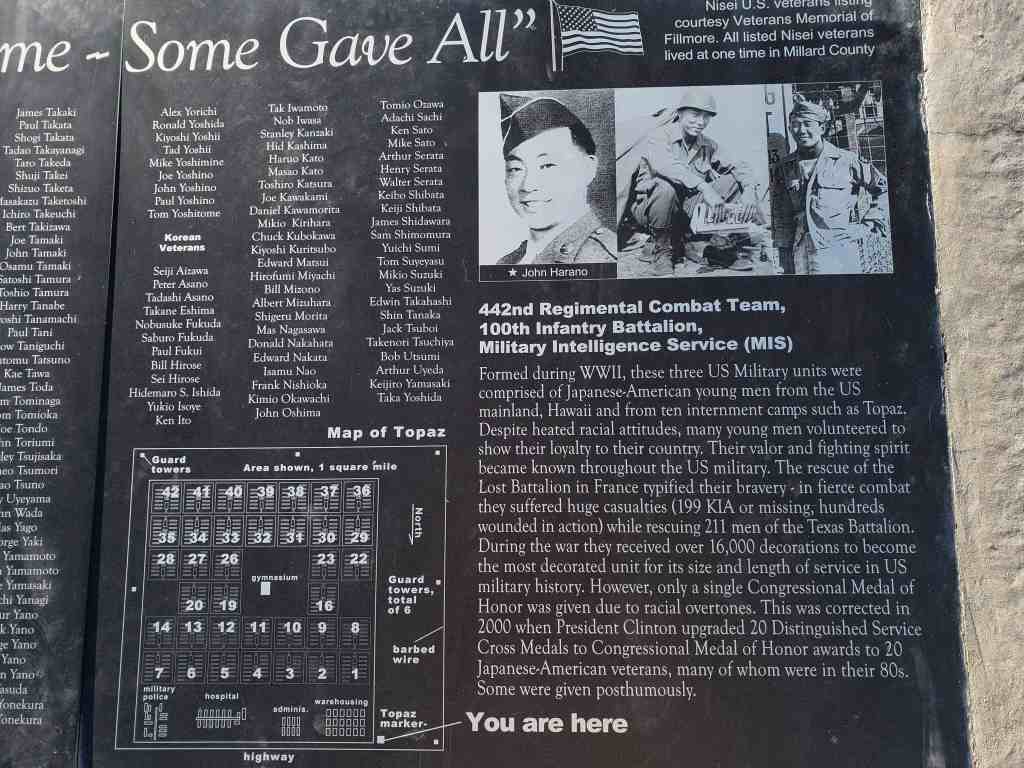

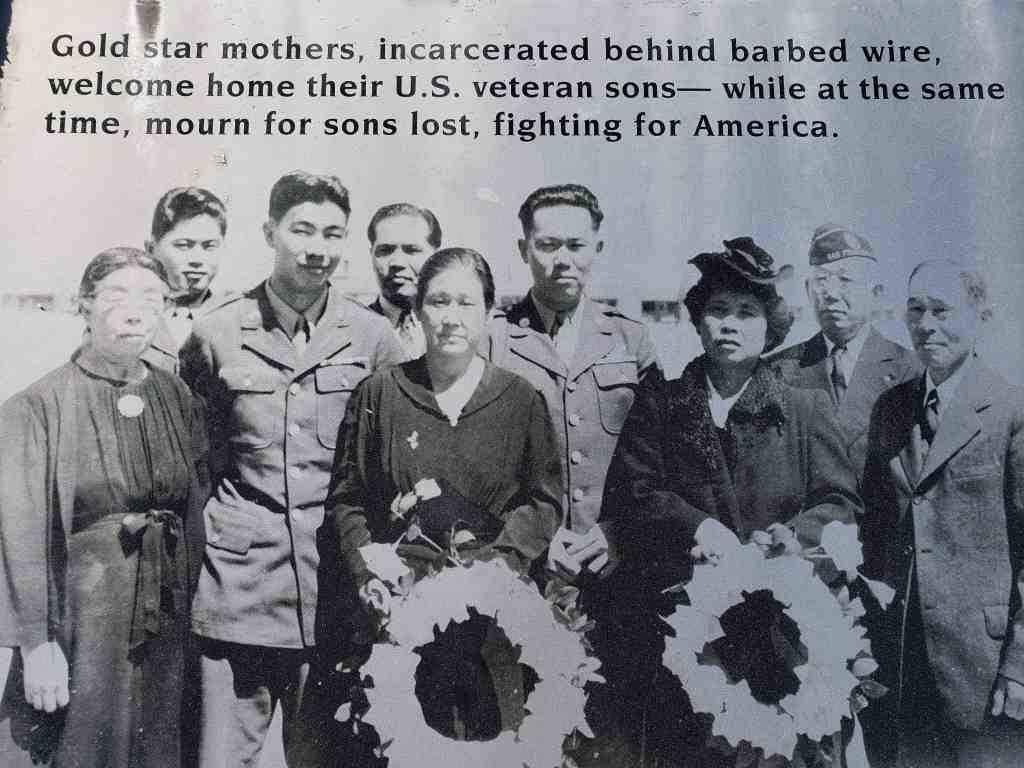

Indeed, the 442nd RCT and 100th Battalion, composed entirely of young Japanese–American boys (many of whom volunteered from internment camps), suffer major war casualties and go on to become the U.S. Army’s most highly decorated combat unit in its history.

Topaz is closed in October of 1945. The memory of Topaz remains a tribute to a people whose faith and loyalty were steadfast – while America’s had faltered.

Related:

- Delta, Utah

- Former Labor and Prisoner of War Camp (Orem)

- National Historic Landmarks in Utah

- Topaz 1942 – 1946 (historic marker in Delta)

- Topaz Hospital (moved to Delta)

The Topaz War Relocation Center Site was added to the National Historic Register (#74001934) on January 2, 1974. The text below is from the national register’s nomination form:

The Topaz War Relocation Center was one of ten camps established in the United States to house the Japanese evacuees: from the West Coast. Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, fear of “enemy aliens!” in the United States was so great that President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Executive Order 9066 which gave the Army blanket power to deal with the enemy alien problem. Under this order General John L. DeWitt, commanding general of the Western Defense Command in San Francisco, issued Public Proclamation No. 1 which announced that all persons of Japanese ancestry would eventually be removed from the West Coast “as a matter of military necessity.” The Wartime Civil Control Administration was established to supervise the evacuation.

At first the evacuation was voluntary and almost 5,000 did move, principally to Utah and Colorado. Many of these voluntary evacuees ran into trouble as they were greeted with “No Japs Wanted” signs and turned back by border guards and armed posses. On March 27, 1942 the voluntary evacuation was halted and the army began a program of compulsory evacuation.

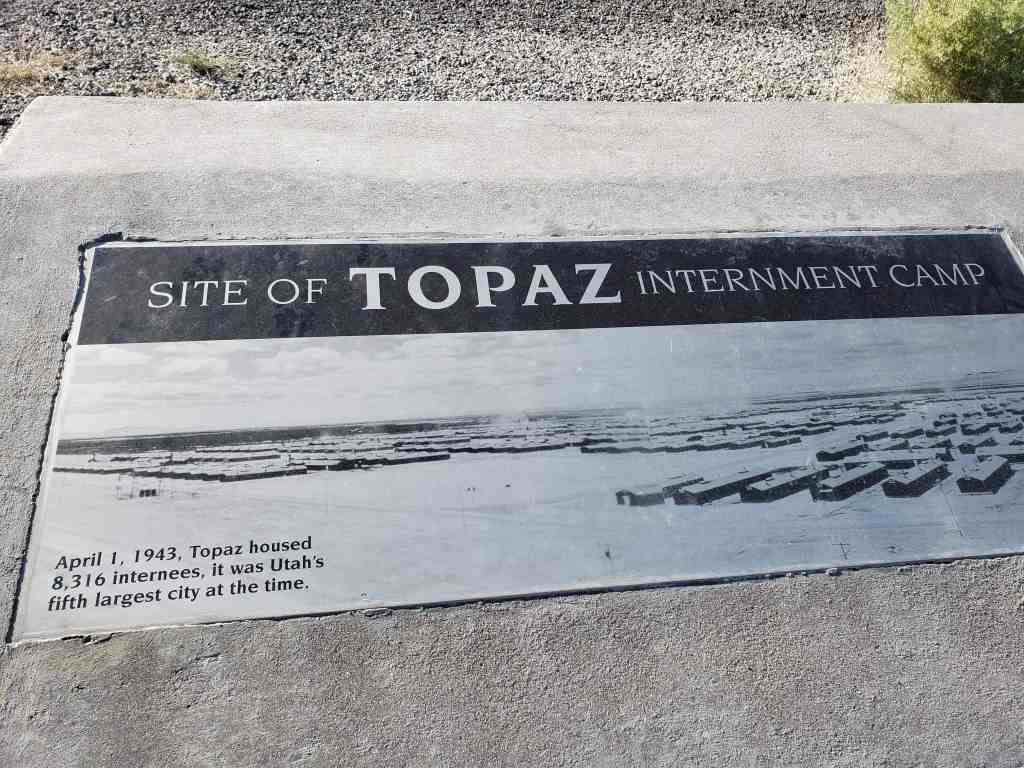

Officially known as the Central Utah War Relocation Center, Topaz was opened September 11, 1942. Named for the nearby Topaz Mountain, the camp consisted of 19,800 acres and was designed to house 9,000 persons.

The camp was constructed between July 1942 and January 1943 by a California firm (Daley Brothers) under a contract let by the United States Corps of Engineers. The cost was $3,929,000 with more than 800 men involved in the construction. The eventual cost was estimated at five million dollars with another five million dollars required annually for the operation of the camp.

Throughout the three-year history of the camp, crime was almost nonexistent among the 8,000 evacuees. There were only two cases of aggravated assault, two of grand larceny and one of destroying government property. Trouble was feared, however, when a sentry, enforcing a camp regulation which forbade any alien to approach the outer fence, shot and killed an elderly Japanese man. A mass funeral was held and a vigorous protest made to camp officials.

Residents of the camp were involved in various enterprises including agriculture, furniture-making, brick making, sheet metal manufacturing and numerous single-employee jobs and services. Most enterprises were intended to meet the needs of the community. Some 3,000 students passed through the Topaz School system. A newspaper Topaz Times was published.

The camp was closed October 31, 1945. Although there are only a few ruins, the site is significant because it symbolizes the extreme degree of prejudice and war hysteria that was directed against Japanese and persons of Japanese descent after the United States entered World War II. Many people feel that Topaz and the nine other war relocation centers in the United States were America’s answer to the Auschwitz or Dachau of Nazi Germany.

The incarceration of American citizens and aliens of Japanese ancestry was for America’s war-time mobilization effort, a grave mistake. The American-Japanese were an important part of California’s economy. In addition to their shops and businesses, they were important in the fishing and agriculture industries of California. The incarceration of all Japanese on the West Coast meant a less vital labor force and required a considerable number of guards and officials, whose energies could have been used in more worthwhile and beneficial aspects of the war effort, to staff the camps.

Of greater significance was the precedent this action set in allowing the basic constitutional rights guaranteed all American citizens, to be denied under a questioned justification of national security.

Many writers and historians have suggested that the basic question, following the bombing of Pearl Harbor, was, “Could democracy really work under all circumstances?” The Japanese-American experience of World War II demonstrates that democracy could have worked but, tragically, was not permitted to. The significant question for Americans of this and future generations is, “What circumstances, if any, justify the denial of the basic rights upon which this country was founded?”

Another significant aspect of the relocation story is what Dr. Roger Daniels describes as, “The logical outgrowth of over three centuries of American experience, an experience which taught Americans to regard the United States as a white man’s country in which non-whites ‘had no rights which the white man was bound to respect.” (Daniels Concentration Camps U .S .A. , p. xii.) Fortunately this part of America’s race problems has been dissolved and America is not blemished by race hatred or discrimination toward the Japanese American. A feeling of sorrow, rather than resentment, would best characterize the American and American-Japanese attitude to the relocation experience and earlier forms of discrimination. This provides an America which has the potential for renewed racial strife with both an example and a hope of reconciliation of all races and groups within its society.

The entire camp covered 19,800 acres; however, the actual center was a mile square with areas for evacuee residents, administrative personnel and military police. The evacuee area consisted of .forty-two blocks of which thirty-four were for living quarters . Each resident block was designed to house and service 250-300 persons. The facilities consisted of twelve single story barracks buildings which were divided into six single rooms, ranging from 16 x 20 feet to 20 x 25 feet in size, a central dining hall, recreation hall, combination washroom-toilet-laundry building, outdoor clothes lines and an office for the block manager.

Pot-bellied stoves, cots, mattress covers and blankets were furnished from army stores. However, evacuees were required to make benches,; tables shelves, closets, storage chests, and other furniture.

The administrative area consisted of eight blocks of one story office buildings, barracks apartments, dormitories, and a recreation center. A total of 623 buildings were constructed during the life of the camp. After the camp was closed, the property was sold. The buildings have all been torn down and there are few remains of the camp which once housed as many as 8,130 evacuees.

None of the 623 buildings constructed during the heyday of the camp remain. They have either been torn down or moved to other sites throughout Millard County.

A few foundations are still visible and the street system is still discernable. However, Topaz, like so many important sites in American history, once there was no further use, has been abandoned and, by many, forgotten, until it has almost been reclaimed by the greasewood, sagebrush and salt grass of the desert from which it was born.

Pingback: Delta, Utah | JacobBarlow.com