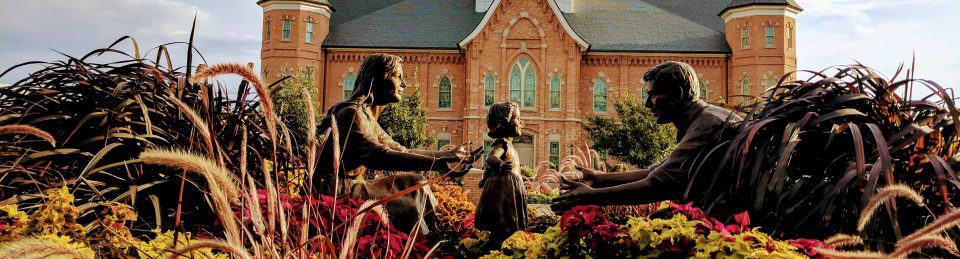

The Salt Lake Northwest Historic District, one of Salt Lake City’s historic districts.

The Salt Lake City Northwest Historic District is a 28-square-block (280-acre) residential neighborhood developed between the 1850s and the 1950s. The roughly rectangular-shaped district includes 1,489 buildings, of which 1150 (77%) contribute to the historic character of the neighborhood. There are 339 (23%) total noncontributing buildings. Of the 248 non-contributing primary buildings, 129 are altered historic buildings and 119 are considered out-of-period. Ninety percent of the contributing buildings are single-family dwellings dating from the mid-1850s to 1950. Six percent of contributing buildings are duplexes, mostly built between the 1890s and 1950. The housing stock also includes several apartment buildings and residential courts. Approximately half of the contributing commercial buildings are found along North Temple. The others are small commercial blocks (often combined with residential space) scattered throughout the neighborhood. Also included among the contributing buildings are four religious facilities and one former library. The district lies just a few blocks north and west of Salt Lake City’s downtown, and is separated from the central business district by several railroad lines near the eastern boundary of 500 West. At the western boundary is the Utah State Fairpark. The district’s north and south boundaries are two major thoroughfares, 600 North and North Temple. (more here)

Single Family Dwellings: Early Settlement Period. 1850s-1879

There are 742 contributing single-family dwellings located within the Salt Lake City Northwest Historic District, only eleven of which have been identified as having been built before 1879. However, historical documents suggest the actual number is much higher. Unfortunately additions, alterations, and the general lack of documentation makes it difficult to come up with an exact number. The eleven also include the district’s two properties previously listed on the National Register: the Nelson Wheeler Whipple House at 564 West 400 North (built in 1854 and listed in 1979), and the Thomas and Mary Hepworth House at 725 West 200 North (built in 1877 and listed on April 21, 2000).

The Whipple and Hepworth houses represent the higher end architecture of the settlement period. The typical small home is represented by the example at 126 North 800 West. Built circa 1870, this house is a 540-square foot hall-parlor with a frame addition. It is constructed of adobe brick covered with stucco on a stone foundation. A more unique example is what appears to be an unfinished Georgian-influenced single-cell house, at 423 North 600 West, probably built in 1868. This unusual house has a number of turn-of-the-century additions, however the main portion is adobe. Only a handful of early frame houses are extant in the neighborhood, and most have been substantially altered. No log dwellings were identified in the reconnaissance-level survey of the area, however it is possible existing log structures may have been incorporated into later additions and covered by a veneer. Most settlement-era homes have little stylistic detail other than classical symmetry. The most common house type from the era is the hall-parlor. Other types are represented by only one or two examples.

Single-family Dwellings: Victorian Urbanization. 1880-1910

Houses representing the types and styles of the Victorian era comprise 39% of the number of single-family dwellings, the largest percentage of associated housing stock in the district. These houses are found throughout the Salt Lake City Northwest Historic District as distinct architectural entities, in tracts of two or three, and occasionally in a residential court setting. Stylistically, a small percentage of these homes demonstrate the transition from earlier houses and possess Classical, Greek Revival or Italianate features. Examples range from early hall-parlors with added wings to late Victorians with Queen Anne-style towers. One interesting example of a transitional house spanning several decades is located at 344-346 North 600 West. This two-story house built in several phases between 1882 and 1954 has walls of adobe, stucco, brick, and frame. The stylistic elements of the house include Greek Revival cornice returns, Victorian details on the octagonal north wing, and Period Revival porch enclosures.

Single-family Dwellings: Early Twentieth Century. 1910-1939

The dominant architectural style of the early twentieth century was the Bungalow. Nineteen percent of contributing single-family houses in the Salt Lake City Northwest Historic District are Bungalows in type and style. The Bungalow was intended to be a comfortable, sheltering, low profile house. While early Bungalows like the one at 578 North Dexter Street were built contemporaneously with Victorian houses, by 1915 the Bungalow had become the everyman’s house replacing the earlier Victorian cottages. Most of the Salt Lake City Northwest Historic District’s Bungalows are modest homes (as are Utah bungalows in general) with little decorative detail, however several in the district are distinctive. The Langton Park Bungalows built in 1918 are a combination of Arts & Crafts and the California styles. Brick Bungalows at 575 West 200 North and 251 North 700 West have a hint of Prairie School influence. A row of brick Bungalows, also from 1924, on 500 North, includes one at 1043 West 500 North with a distinctive porte-cochere. The description of Bungalow as a type, as well as a style, fits most of the Bungalows in the district. The houses usually have the narrow end to the street with a variety of roof styles (simple gable, hipped, and clipped gable), and a full or half-width porch. The few Foursquare houses in the district are modest in size with bungalow influence and are not similar to the traditional two-story, upscale Foursquares found in other parts of Salt Lake City. The most popular material for Bungalows was brick, with wood and stucco used for decoration. Frame Bungalows are also found throughout the district, though many have been altered. Stone was used as a foundation material in early Bungalows, however after 1915, concrete was used increasingly. During the Bungalow period, the use of concrete — as well as better drainage — increased the occurrence of fully excavated basements. The Bungalow period also has examples of new materials such as striated brick and concrete block. There is even one brick Bungalow with a volcanic rock veneer on its lower half.

After World War I, the Bungalow remained popular, but the Period Revival movement favored by veterans who had served in Europe was evident in the architecture of the 1920s in Utah. Several Bungalows, built in 1926, along 1000 West near 400 North show some period revival details. Within the Salt Lake City Northwest Historic District, construction of residences slowed considerably between the late 1920s and the start of World War II. Period revival cottages account for only three percent of houses in the area, a percentage much lower than contemporaneous neighborhoods on Salt Lake City’s east side. Among them are modest English period cottages like the one at 878 West 500 North, built in 1929, and four found on Chicago Street, built between 1928 and 1929.

Single-family Dwellings: World War II and Post-World War II Era. 1940-1950

Twenty-nine percent of single-family dwellings in the Salt Lake City Northwest Historic District were built during the 1940s. Surprisingly, a number of homes in the district were built in the early 1940s, although access to materials and labor was severely restricted. Two examples from 1941 represent the World War II Era. The house at 843 West 500 North is one of nine houses (some brick, some frame) built on the block, and typifies the minimal traditional house developed by Federal Housing Administration to promote home ownership during the depression. The “minimal traditional” elements of 863 West 500 North are evident in its modest 865 square-foot (two-bedroom) footprint, and limited decorative brick details. A more unique example is found at 460 North Chicago Street, another small square, brick masonry house with corner metal casement windows giving it a more Modern appearance.

Multiple-family Dwellings: Duplexes (Double Houses) & Apartment Buildings

Six percent of residences within the Salt Lake City Northwest Historic District are duplexes (also known historically as double houses), with another one percent being historic apartment buildings. Approximately half of the duplexes were built between 1890 and 1910, and are found both along the main streets and in residential courts between 500 and 800 West. Stylistically, these early duplexes come in two varieties: the urban model with a flat-roof and decorative brick parapets; and the more domestic-looking, hipped or gable roof structure. Despite being rental units (or perhaps because they are rentals), these duplexes have survived relatively intact with only minor changes, such as the replacement of the classical porch columns with wrought iron. Brick masonry was used for most of these buildings, however there are a few frame examples such as the duplexes at Tuttle Court. The remaining half of the duplexes date from the Bungalow era or the post-World War II period, and with few exceptions, are found in the western half of the district. Many, especially later, duplexes are found on corner lots as part of rental buffers for subdivision development. A few are frame-sided or stucco Bungalows, including one Langton Park triplex, but most are brick structures from the late 1940s.

There are six historic apartment blocks in the Salt Lake City Northwest Historic District. All are small with only four to six units, not big enough to be classified as walk-ups. The oldest is the four-unit block at 540 North 600 West, built in 1897 and later converted to commercial use. This building features decorative brickwork on the parapet and originally had a full-width porch and balcony. Not far from this building stand the most recent historic apartments, twin six-unit blocks at 545 and 555 West 500 North, built fifty-years later in 1947. The two-story Boyer Apartments, as they were known, were constructed of brick with pyramidal roofs and minimal traditional detailing.

Commercial Buildings

Ironically, nearly one-third of contributing commercial buildings identified in the Salt Lake City Northwest Historic District historically combined residential space with commercial use. An interesting example is located at 613 West 200 North where a 1910 frame shop was built in front of and connected to an 1871 adobe hall-parlor. In contrast, at 776 West North Temple, the commercial block came first in 1888, followed by the six-room residence, in 1895, both with elaborate brick work. In other cases, the residence space is less obvious. The 1905 commercial block at 246 North 600 West was built in front of an 1880 house. Also built in 1905, the brick commercial building at 730 West 400 North was built with a second-floor family flat incorporated in the original design.

One of the most significant and prominent commercial buildings is the Horsley Building located at 606 West North Temple and constructed in 1912. The Horsley Building resembles a small hotel court in the commercial style with retail space on the main floor and sixteen apartments on the second. Among the non-residential commercial buildings is the former LDS Church 22nd Ward Cooperative Store at 480 West 500 North. The remainder of historic commercial buildings represents a miscellaneous mix of period and style. Two of the more significant examples are the auto garages built at 319 North 800 West in 1928, and the Romney Motor Lodge, built in the 1940s, one of the few remaining historic motel courts left in Salt Lake City.

Institutional Buildings

While the contributing institutional buildings in the Salt Lake City Northwest Historic District are few in number (five), they present an architecturally impressive group of historic resources. Four are ecclesiastical buildings originally associated with the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church or Mormon Church), and one is a former Salt Lake City branch library. The oldest is the 28th Ward Meetinghouse built in 1902 and located at 750 West 400 North. The building is constructed of brick on a stone foundation in the Gothic Revival style. In 1914, the building was enlarged to the rear with an unusual semi-circular addition that included an auditorium, amusement hall, and classrooms. Though no longer used as a church, the building retains a high degree of historic integrity.

The 34th Ward Meetinghouse at 131 North 900 West, built in 1921, is a brick Neo-Classical structure on a raised basement. The temple-front façade features six massive Doric columns supporting a pediment. This building has been modified somewhat over the years but still retains its historic character. The south wing of the 16th Ward Meetinghouse was built on the site of an earlier chapel destroyed by fire at 129 North 600 West. The new chapel, constructed between 1929 and 1930, is based on a standard meetinghouse design nicknamed the “Colonel’s Twins” because of the two projecting wings, one for the chapel and one for the amusement hall. The 16th Ward building is a brick structure and incorporates Colonial Revival motifs such as keystone, round arches, and cornice returns. This building, used for many years as a Catholic community center, and currently a residence, is in excellent condition.

The Riverside Stake Center, the only meetinghouse within the Salt Lake City Northwest Historic District still used by the LDS Church, is located on the west side at 947 West 200 North. Constructed in 1952-1953, this building is an early example of postwar modernism institutional architecture in Utah. The building is constructed of brick, stone veneer, and cast concrete. The main entrance is recessed under a swooping canopy. The building is in excellent condition and has had only minor alterations.

One of the most historically significant buildings is the Our Lady of Guadalupe Catholic Church located at 731 West 300 North. However the building is non-contributing because a 1972 expansion has obscured the original chapel relocated to the area from an army base in Kearns in 1947. Another significant building is the former Spencer Branch Library, located 776 West 200 North, was built in 1921. The library is T-shaped in plan and is constructed of striated brick. The broadside faces the street with a symmetrical façade. Classical and Colonial Revival details are found in the concrete keystone and end stones of the round relieving arches, and in the Tuscan columns supporting a rounded pediment at the main entrance. The building is currently owned and maintained by the Free Church of Tonga and has seen little exterior alteration.

Outbuildings

Though the Salt Lake City Northwest Historic District retains a semi-rural feel, the hundreds of coops and sheds once found in the rear of nearly every property have all but disappeared. With the possible exception of the circa 1880s stone granary in the rear of 165 North 900 West, extant outbuildings in the Salt Lake City Northwest Historic District are not individually significant. Garages, which began appearing in the district in the late 1910s, make up the vast majority of the 461 contributing outbuildings identified in the 1991 reconnaissance level survey of the area. These garages are mostly single-car, simple-gable frame structures that face the street. The alleys platted by the turn-of-the-century subdivisions appear to have been vacated early (most in the first half of the century) and few garages were accessed from the alleys.

The History of the Salt Lake City Northwest Historic District

Early Settlement Period. 1847-1869

On July 24, 1847, a small contingent of members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS or Mormon Church) entered the Salt Lake Valley under the direction of Brigham Young. On August 2, 1847, a little more than a week later, Orson Pratt and Henry G. Sherwood began to survey what was then known as the City of Great Salt Lake. In less than a month, the survey of Plat A, consisting of 135 blocks, was completed. The land was divided into ten-acre blocks, each containing eight lots of one and one-quarter acres. Streets were 132 feet wide. Only one house could be constructed on each lot with a standard setback of twenty feet from the front of the property. The rear of the property was to be used for gardens and outbuildings. Farmland was provided in the outlying areas. Forty acres were set aside for the temple, and four other blocks were for public grounds to be laid out in various parts of the city. After the church officials selected lots for their personal use, the remainder of the land was divided by casting lots. Scarce resources such as timber and water were to be held in common with no private ownership. Within two years, the population of Salt Lake City had grown to 6,000. Plat B was laid out in sixty-three blocks to the east in 1848, and in 1849, the eighty-four blocks of Plat C were surveyed on the west side. The Salt Lake City Northwest Historic District consists of five blocks along the western edge of Plat A and twenty-three blocks of Plat C.

In February of 1849, the city was divided into nineteen wards of the LDS Church and a bishop was selected to preside over each ward. The northwest portion of the city was within the boundaries of the 16th ward (South Temple to 300 North, and 300 West to the Jordan River) and the 19th ward (a triangle-shaped area 300 North to Beck’s Hot Springs [800 North], and 300 West [base of the foothills] to the Jordan River). Though lots were allocated and the basic governing (church) hierarchy in place, early settlement proceeded slowly. Most of the earliest settlers spent their first few winters in crude log cabins, tents, or in wagon beds, in or near the fort (present day Pioneer Park at 300 South and 300 West). A few houses were built in the 16th Ward in 1848, but the church’s official historian was “unable to find out positively whether any of the pioneers of Utah built houses or resided in the Nineteenth Ward prior to 1849, although it is possible that one of two families became settlers in 1848.” By 1850 a number of settlers had moved to their lots and begun building permanent homes. Some of the houses may have been log (newly hewn or relocated from the fort site), but most were built of adobe (or mud-dried bricks). An adobe pit was first established near the fort site in order to provide bricks for the fort wall, and later brick was available for home building.

The majority of these houses were single-story, one or two-room (single cell and hall-parlor) dwellings, which were plastered as soon as the owner had the resources. The Nelson Wheeler Whipple House, an eight room, two-story house built in 1854, was one of the few exceptions. Whipple, who immigrated to Utah in 1850, had various occupations (policeman, gunsmith, carpenter, cabinet maker and superintendent of the Municipal Bath House), but is best known for his lumber business and shingle mill. The house at 564 West 400 North (within the 19th Ward boundaries) was home to his entire family: himself, three wives and seventeen children. The house was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1979.

From the beginning, the west side of the city was less desirable for settlement than the east. Topographically, the northwest district is one of the lowest areas within the city limits and before the advent of drainage systems, was often covered with water. Some improvement came in 1856 when the three channels of City Creek were directed along North Temple to the Jordan River, and land west near the river was reclaimed. However, the poor-quality alkaline soil and brackish water of the Jordan River prevented extensive cultivation and the land was used mostly for pasturage. An October 1852 census of members in the 19th Ward numbered 300 people in addition to about 100 children under the age of eight, however most of those lived east of 300 West in the Marmalade District. Four years later, Frederick Kesler, bishop of the 16th Ward, concerned for members of his ward, visited every dwelling to ascertain the amount of provisions on hand. He recorded visiting “521 souls” in 132 houses. Frederick Kesler (1816-1899) was a prominent millwright whose engineering skills and inventiveness contributed much to the early economy of Utah. Kesler was bishop of the 16th Ward for forty-three years, and died at his home at 556 West North Temple (now demolished).

Salt Lake City grew quickly in the two decades between 1847 and 1869, and has been described by many historians as an “instant city.” The population increase was steady, supported by the annual influx of Mormon convert immigrants, mostly from England and Scandinavia, and the characteristically high Mormon birthrate. While the arid soil and necessity of irrigation systems made crop production difficult, the cash crop of gold dust left in Salt Lake City by “forty-niners” traveling to and from California gave rise to a thriving mercantile district in the center of town. The overall economy benefited by this traffic, and early Utah settlers gradually became more prosperous. The city was incorporated in 1851 with many lines of the original charter devoted to regulating burgeoning commerce. On the west side, just as on the east side, families built new homes or enlarged older ones, often relegating former log cabins to outbuilding status. By the late 1860s, Salt Lake had several brickyards, and though small adobe houses were built up until the 1880s, brick became the most sought-after building material. The houses were surrounded by shade trees usually lindens and poplars. The settlers dug irrigation ditches and built fences around their lots, planted gardens and small orchards, and raised whatever livestock was necessary for family subsistence. Most heads of households were merchants, mechanics, or artisans.

Victorian Urbanization and the Coming of the Railroad. 1870-1910

Historians generally agree that the completion of the transcontinental railroad on May 10, 1869, is a benchmark in Utah’s history: the official end of the pioneer era in Utah. In January of 1870, the Mormon church-sponsored Utah Central Railroad completed a line connecting Salt Lake City to the Union Pacific line at Ogden. In 1872, Union Pacific acquired control of the Utah Central, as well as interests in another Mormon railroad, the Utah Southern, which ran south from Salt Lake to Provo. The 400 West corridor provided the best grade and location for the tracks, and within a few years a warehouse district had developed next to the city’s central business district. The coming of the railroad had a direct effect on the neighborhoods west of the track for even one track created a barrier to east-west movement. By the time of the 1889 Sanborn map, the Utah Central-Union Pacific Railroad had laid six lines of track near 500 West, and the Denver & Rio Grande Railway, which had completed its Salt Lake to Denver line in 1883, had a track running north to south along 700 West. The 1898 Sanborn map shows that in the decade before the turn of the century, the Oregon Short Line Railroad (incorporated by Union Pacific/Utah Northern Railway) had laid seventeen sets of track (through lines and sidings) separating the west side of town from the east at 500 West and North Temple.

The impact of railroad on the settlers was mixed. Many early residents simply left. Samples of title abstract records indicate a number of “original occupants” of the Plat C blocks did not maintain their ownership when deeds began to be officially recorded by the federal land system in the 1870s. Patty Sessions (1795-1893), one of Utah’s most prolific midwives, had lived near the corner of North Temple and 500 West since 1850. In 1870 she sold her property to the Utah Central Railroad and moved to Bountiful, Utah. Some early residents sold their property to their neighbors, and others sold to land speculators from outside the area.

The relative proximity of the tracks determined development patterns in the decades after the coming of the railroad. The area nearest to the tracks, 500 West and 800 West, experienced tentative development and the original pioneer lots subdivided and built-up with a random mix of cottages, duplexes, residential courts and commercial buildings. In contrast, the land west of 800 West was suburbanized and subdivided in a late nineteenth-century real estate frenzy, which peaked in 1888, when the Salt Lake County Surveyor was authorized to approve all plats and maps. Between 1888 and 1903, ten subdivisions were platted within the northwest district’s boundaries. The interest in subdivision development on the west side may have been stimulated by the 1889 electrification and subsequent expansion of the city’s streetcar system that produced a streetcar line on North Temple from the central business district to 1000 West.

A look at three subdivisions illustrates the variety of persons involved in developing the area. William Langton (1854-1928) and his wife Frances Alma Jones Langton (1859-1941), were longtime residents of the 16th Ward. Not only were they involved in the Langton Park Subdivision of 1896, they built a number of duplexes and other properties in the neighborhood. According to one tribute, William Langton “did much to promote building of homes on the west side of Salt Lake City.” Dr. Leslie W. Snow (1862-1935) and his wife Ida Daynes Snow (1871-1955), who developed the Snow Subdivision in 1903, were Utah natives and members of the LDS Church, but never lived on the city’s west side. Arvis Scott Chapman (1839-1919), William J. Lynch (1862-1931), and Isadore Morris (1844-1906) who platted the Oakwood Subdivision on behalf of the Mount Moriah Masonic Lodge in 1903, were entrenched eastsiders and non-Mormons to boot. While some Salt Lake real estate speculators turned a profit, west side speculation remained just that. Many lots in these turn-of-the-century subdivisions were not built upon until the 1950s. The disadvantages of the west side were numerous. During high water seasons the neighborhoods were flooded both from the Jordan River backing up into the irrigation ditches and the City Creek water flowing from the higher levels of the city. In referring to the 1893 typhoid epidemic, the city health commissioner stated, “It is from poor drainage and seepage from privy vaults and cesspools, a condition so much facilitated by this low and damp section of the city, that presumably, is the cause…for the preponderance of typhoid fever in that section over that of any other in the city.” By the 1890s, the west side had become the official and unofficial dumping ground of the city. Because the crematory, located near Warm Springs, could not process all of the city’s “night soil,” trenches were dug at a site half a mile west of the Jordan River and the sewage coverage with two feet of dirt, a practice repeatedly objected to by west side residents. In 1894, the canal running along 900 West had become the receptacle for so much stagnant water and filth that it was condemned and filled.

Transportation was another major deterrent to development. Movement over the tracks was discouraged due to the danger of fast running trains and the delay of slow and standing ones. The streetcar system that had proliferated on the east side was limited to two lines in the west. In addition, street improvements were late in coming to the west side. While streets began to be paved, curbs and gutters installed, and sewers placed in some sections of the city beginning in the 1890s, parts of the west side were without these improvements until the 1920s. Water mains and pipes (replacing well water) were laid in 1890s, and City Creek was partially channeled underground. The west side eventually received electricity by the turn of the century.

Despite problems, the railroad era brought modest prosperity to the west side. One-third of all historic buildings in the Salt Lake City Northwest Historic District were constructed during this period. Cottages, and a few fancier homes, built with fired brick, both as structural material and as a veneer over adobe, appeared all over the district. The Thomas and Mary Hepworth House, built in 1877, is a distinctive house that represents an early transition from the pioneer era to the Victorian era. Thomas and Mary immigrated to Utah in 1852, and in 1872 purchased a piece of property on the west side, where they live for five years while Thomas built up a family meat market. In 1877, the house at 725 West 200 North was built of fired brick. The Hepworth House is the only remaining example of a two-story central-passage house with vertical Victorian proportions and Italianate ornamentation in Salt Lake City. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in April 2000.

The Victorian Eclectic cottage, most often a cross wing constructed of brick, became ubiquitous in Salt Lake City, and a number of beautifully preserved examples can be found in the northwest district. The central block with projecting bays was another popular house type in the district. The frame house was also very popular as the railroad brought lumber into timber-scarce Salt Lake City. The railroad also had an impact on the decorative aspect of domestic architecture. The rather austere classical adobe houses of the pioneer period were essentially vernacular buildings meant to mimic the houses the early settlers left behind in the east and mid-west. With the coming of the railroad, access to a variety of materials, and the availability of pattern books and handbooks, allowed local builders to produce exact replicas of Victorian cottages being built all across the United States. Ornamentation such as lathe-turned porch posts, spindle work and sometimes “gingerbread” cut woodwork was found on Victorian cottages throughout the district. In addition, many of the older homes converted to cross wings and/or “dressed up” with Victorian ornamentation in the 1880s and 1890s.

Multiple-family housing began to appear in the district in the early 1890s. According to one report, in April of 1888, there was a “scarcity of rentable houses and a great demand for them,” particularly four-room cottages for small families. The most popular type of multiple-family housing was the double house, or duplex. Most were brick, some were frame, and the earliest examples resembled Victorian cottages with gable roofs and wood ornamentation. The Tuttle Court complex, built by Mary Anne Taylor Tuttle (1832-1924) around 1895, has four of the oldest and best-preserved frame examples in the district. The original owner of multiple-family housing was often a builder or businessman who lived nearby. The circa 1904 brick duplex at 745-747 West Jackson Avenue was built by William H. Jones (?-1935?), a carpenter who lived at 635 West 400 North; and the circa 1900 brick triplex at 216-218 North 800 West was built by Kay Bridge (1876-1952), a plasterer, living at 666 West North Temple.

Several commercial buildings, mostly one and two part blocks, were constructed during this period. Near the tracks was the Solomon Brothers’ Shoe Factory and David James’ pipe factory (neither building is extant). By the late 1890s, North Temple Street had the beginnings of a commercial strip with a cobbler, a blacksmith, a bakery and a meat market. One of the oldest surviving buildings was built in 1888, when Arthur Frewin (1855-1940) built a general mercantile business at 780 West North Temple. Four years later he built an addition on the back, and in 1895 built a residence for his family adjoining the store. The enterprise appears to have been quite prosperous, as is attested by the large typeface of his name in the city directories, and the quality of the corbelled brickwork on both buildings. More modest one-part block examples include the 22nd Ward Cooperative store, which stills stands, though somewhat altered at 580 West 400 North; and the frame store/tinshop attached to an adobe hall-parlor at 613 West 200 North. Two-part block examples include 815 West 300 North and 730 West 400 North, both somewhat altered by façade siding.

Economically, the neighborhood was still represented by a solid merchant/artisan middle-class, but many had new urban jobs: clerks, bookkeepers, agents, civil servants etc.; however, two major changes in the economy occurred during this period: 1) the need for family subsistence farming dropped dramatically, and 2) approximately 1 out of every 5 heads of a household worked for a railroad or a railroad-dependent industry at least some time in his life. Many had long-term commitments. Willard W. Bywater (1853-1915), a Welsh LDS convert, was, for many years, a pattern maker for the Oregon Short Line Railroad. Bywater’s neighbor at 155 North 700 West, Robert Bridge, Jr., (1871-1942), a Salt Lake City native, spent 50 years as a sheet metal worker for the Union Pacific.

Just as in the pioneer era, the population growth of the district was steady. When the Jackson Elementary School at 750 West 200 North was built in 1892, it was one of the largest schools in Salt Lake City (the building was demolished and replaced by a new building in the 1980s). The growth of the Mormon population necessitated a split of the original 19th Ward. In 1889, the 22nd Ward was created from the west portion of the 19th Ward. Two more wards were created from the 22nd in February 1902, when the western half was divided: the 28th Ward (railroad tracks to 900 West) and the 29th Ward (900 West to the Jordan River). By the end of that year, both congregations built Gothic Revival chapels: the 28th Ward at 750 West 400 North, and the 29th Ward (just outside the district boundaries) at 1104 West 400 North. The LDS ward meetinghouses in the area served as social centers, as well as worship spaces, for the community. In winter, when snow and mud made the journey to town unpleasant and treacherous, “plays, operettas, vaudevilles, and minstrel shows,” often produced by ward members, were scheduled in the meetinghouses. Non-Mormon social centers were also built. The Methodists had a small church at the corner of 800 West and 400 North, the Endeavor Presbyterian Church was located at 630 West 200 North, and there was dance hall on 600 West (none extant).

The railroad, as well as the mining and smelting industries it supported, brought thousands of immigrants to Utah. Within the LDS community, the immigrant converts established neighborhood enclaves (e.g. “Danish Town” was the nickname for a block on Marion Street where a number of Danish immigrants lived, and in the 100 block along 700 West, a number of Welsh converts built homes). These LDS immigrants assimilated quickly and easily into the Utah’s cultural climate, but for other immigrants the process was not so easy. As LDS convert immigration (primarily from Scandinavia and the British Isles) declined in the last three decades of the 19th century, non-Mormon immigration increased. A small percentage of Chinese, who came with the railroad, stayed to make homes in Salt Lake City. The majority of Chinese lived near Salt Lake’s Chinatown, located near downtown and centered around Plum Alley which ran north from 200 South to 100 South between Main and State streets; however, 1898 Sanborn map shows three Chinese vegetable gardens with “shanties” in the neighborhood around 700 West and 300 North. Other ethnic enclaves were established near the tracks just south and east of the northwest district. Greek Town consisted of more than sixty businesses lining 200 South between 400 and 500 West streets. A small Italian community, Little Syria and Lebanese Town were also near the tracks. Non-Mormons (mostly the ethnically diverse immigrants who came to work in the railroad and mining industries) lived in the southern and western portions near downtown while Mormons and the more affluent, longtime-resident non-Mormons lived to the north, east, and the southeast. Only a few of the recent immigrants lived in the rental duplexes and houses available in the northwest district at this time. However in the first half of the twentieth century they would gradually move from the “ethnic ghettos” north to become home and business owners in the northwest neighborhoods.

Immigration and Industrialization. 1900-1929

By the turn of the century the Salt Lake City Northwest Historic District, had all the makings of a middle-class streetcar subdivision with neighborhoods consisting of attractive homes, gardens, and shade trees, and a few prestigious commercial buildings. The Horsley Block, a large commercial building with apartments, designed by the prestigious Salt Lake architectural firm, Pope & Burton, was built at 606 West North Temple in 1912. The vacant land at the west end, known as the Deseret Agricultural & Manufacturing Society Fairgrounds & Race Track, was officially designated as the site of the Utah State Fair in 1902. The fair grounds (just outside the district boundaries) include a number of architecturally significant structures built in the first quarter of the twentieth century and was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1981. City services improved greatly during this period. After two disastrous floods in 1908 and 1909, during which North Temple was navigable only by boat, the drainage and sewage systems of the west side became a priority. The North Temple viaduct was completed over the Oregon Short Line tracks in 1912. City streets were paved and some curb and gutter installed by 1926.

However, though part of the northwest district remained middle-class, the neighborhoods closest to the railroad tracks became increasingly working-class. Economically more diverse, but because the newer immigrant populations were subject to prejudice, not ethnically or religiously more diverse. In a 1914 University of Utah thesis written on The Housing Problem in Salt Lake City, the author noted, “the landlords prefer Americans to Southern Europeans…Thus when Italians, Greeks, Japs or Chinese apply for a house and the landlord is particular who shall occupy the place, the rent is a little higher than for the ordinary houses in the same locality and of the same size.” Thus for the most part, the majority of residents of the northwest district, including renters, were homogeneous to the residents in the last half of the nineteenth century.

The store at 730 West 400 North illustrates the gradual shift in population in the neighborhood. In 1905 Henry Walsh (1866-1933), and his wife Ruth May Brown (1870-1936), built a two-story commercial block building with a grocery store on the main floor and residential space above. Apparently the grocery business did not provide all of the family’s needs for by 1910 Henry was working as a watchman for the railroad and Ruth was running the store. In 1916, Joseph Balzarini, an Italian immigrant with a Hungarian wife, bought the building and also operated a grocery. Joe Balzarini sold the store to the Caputo family. Rosario (1883-1970) and his wife Cristina (1888-1979) Caputo were also Italian immigrants who not only ran a successful business for nearly half a century, but also raised eleven children in the upstairs apartment. In addition the Caputo store was the neighborhood’s de facto community center for Italian Catholics, peacefully coexisting with the LDS 28th ward house across the street.

Meanwhile, the LDS community continued to thrive. The 28th Ward built an amusement hall addition to the chapel in 1914. Another division came when the 34th Ward was created and a Neo-Classical chapel built in 1921 at 131 North 900 West. One of the greatest assets came to the community when the John D. Spencer Branch of the Salt Lake City library was built in 1921 at 776 West 200 North. The classically styled building designed by prominent Utah architect Joseph Don Carlos Young was built next to the Jackson Elementary school making the block a natural venue for community gatherings.

In the northwest neighborhoods, a subtle physical change was taking place. Numerous Bungalows began to appear throughout the district as infill and in tracts on previously subdivided lots, and the semi-rural feel of the neighborhood was lost in urban density. Blacksmith shops disappeared, and in 1928, the Earnshaw family built an auto garage and service station at 319 North 800 West. The barns, coops, and other outbuildings in the backyards and along the vacated alleys were demolished and replaced with automobile garages. The number of homes with garages during this period was only about twenty percent and most residents still relied on the streetcar or their own two feet for transportation.

The greatest change to the northwest district was an economic change. The ratio of railroad workers to nonrailroad workers increased dramatically from the previous decades. In fact, in the 1910 census enumeration for the district, the percentage of heads of household who list “railroad” in the type of industry column ranges from 25 to 50 percent for some streets. There appears to be a slight decrease in the 1920 census. In the following sample of housing built during this period, the dominance of railroad-related occupations is illustrated. Of the two men who lived in the 1908 flat-roofed brick duplex at 235-237 North 600 West, one worked for an electric company and the other worked at the Garfield Smelter. Living in a row of 1909 Victorian cottages near 1000 West and 400 North, two-thirds of the adult male residents held railroad jobs. A survey of the original residents of fourteen Langton Park bungalows (built in 1918) along 900 West, states “the majority of the residents worked for the railroad — either the Oregon Short Line or Denver and Rio Grand [sic] as switchmen, brakemen, baggage agent, signal man, fireman, or as conductors.” Three out of four original occupants of four period cottages, built in 1928-1929, on the 300 block of Chicago Street worked for the railroads.

Depression Years and the World War II Era

With the notable exception of the 16th Ward’s new Colonial Revival style chapel and amusement hall built at 129 North 600 West in 1930, there is little evidence of construction activity in the northwest district during the few years after the start of the Depression. By 1935 more than one in five Salt Lake residents were on relief, and one in three of the rest lived below the poverty level. The residents of the district, like their counterparts throughout the nation, survived as best they could. Many people in the northwest district lost their jobs or were on reduced salaries. The Works Progress Administration (WPA) and the construction-related Public Works Administration (PWA) programs may have provided jobs for a few. The few possibilities for such work in the area were street and sewage improvements, projects at the fair grounds, and the municipal airport. The LDS Church’s Welfare Plan, established in 1936, helped provide food and employment through the several LDS wards in the neighborhood. Many residents worked odd jobs, started cottage industries, planted gardens in those oversized city lots, and sent their children to gather stray chunks of coal dropped by passing trains. During this period, many of the residential courts and private streets, which had never been under city oversight, fell into squalor and disrepair.

In the early 1940s, just as the nation was beginning to rebound economically, some new housing was built in the northwest district. Most are scattered individual homes, but one large tract of nine houses built in 1941 on the 800 block of 500 North is noteworthy. The small, square, brick and frame houses were based on “minimal traditional” designs produced by the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) during the depression to encourage home ownership. Not surprisingly, the majority of original owners of these cottages had railroad-related jobs. One of the casualties of the depression was the streetcar system. In 1941 the last trolley took a final ceremonial run down the streets of the Salt Lake City. A shortage of gasoline put electric-run trolleys back into service for a brief period during World War II, but by 1945 the trolleys were once again forced to retire. Jobs returned to the west side as the advent of war kick-started railroad, smelting, and other important wartime industries.

Post-War Suburban Expansion and Post-Freeway Isolation. 1945-1950s

At the end of World War II, post-war housing was at a premium. In January of 1946, the FHA estimated that Salt Lake faced a shortage of six thousand housing units. In the northwest district, builders responded by filling up nearly every vacant lot with World War II era cottages and early ranch-type houses, especially in the western portion of the district away from the railroads. In contrast, the eastern edge saw little residential construction beyond the twin six-unit apartment blocks (built 1947) near Turtle Court, and the small-scale industries along the railroad expanded. To the south, North Temple began to take shape as a commercial and transportation corridor with new motels, restaurants, service stations, and a supermarket taking the place of many nineteenth century homes and businesses. And, north of 600 North (just outside the district boundaries), in 1946, construction began on the ambitious Rose Park subdivision, where many of the northwest district’s residents would eventually relocate.

The end of World War II also saw a change in the economics of the Salt Lake Valley. The era of railroad dominance began to decline as the trucking industry, which had been growing steadily since the 1920s, outpaced the railroads in freight transport. A decade after construction, only two workers living in the 1941 houses on 500 North still had railroad jobs. Another change had occurred and the same street, which had been fairly homogeneous in 1941, now had neighbors with names like Hatanaka, Hoopiiania, and Gonzales.

One of the pivotal movements for the northwest district came in 1947 when the Our Lady of Guadalupe Parish, an offshoot of the St. Patrick’s Catholic Parish, bought property at the corner of 300 North and 700 West. A surplus army chapel from Camp Kearns was purchased and relocated to 715 West and 300 North. Mexican and Mexican-American families moved to the area, many to take the remaining railroad jobs. As the Spanish-speaking population grew, so did the Guadalupe Parish’s auxiliary organizations to support them. The neighborhood LDS churches also changed during this period. As the population of the Rose Park area grew, the LDS Church changed boundaries and most of the northwest district was included in the newly formed East Riverside Stake. In 1952-1953, a large conference hall for the new stake congregation was built at 947 West 200 North.

Physically, the biggest change to the district during this time appeared in the mid-1950s. The Denver and Rio Grande line down 700 West was pulled up to make way for Interstate 15. With the completion of the freeway in 1956, the west side neighborhoods were even further isolated from the rest of the city. The construction of the freeway destroyed whole neighborhoods between 600 and 700 West, and the value of the remaining homes was greatly reduced. One man living on 700 West, complained to the county tax assessor in a letter that he “couldn’t get an offer at any price” on his house. The only place within the district to cross the freeway was located at a 300 North underpass.

Salt Lake City’s West Side: 1960s-2000

The history of the Salt Lake City Northwest Historic District in the last half of the twentieth century is an interplay of economic change, cultural diversification and neighborhood solidarity. The district has remained solidly working class. A number of medium-density apartment complexes were built in the area in the 1970s and 1980s. The institutional buildings have changed. The old Jackson school was torn down and replaced with a more modern one. The Spencer library closed its doors in 1964, when a new Rose Park branch was opened. The library served for a time as a Rape Crisis Center, and is currently owned by the Free Church of Tonga in America. First Step House, a counseling and transitional housing center, acquired the LDS 28th Ward building. Nearly all the historic buildings along North Temple disappeared, replaced by strip malls, fast food restaurants, etc. The remaining commercial buildings scattered throughout the district have changed uses: the Caputo store is an artist’s studio, and the old Haslam store on 600 West is a boxing club. The Horsley building now serves as the American Plasma Center.

The Salt Lake City Northwest Historic District has a high reputation for community services. The Capitol West Boys’ and Girls’ Club is located in the district. The Guadalupe parish established a stronghold in the district, and in 1972, built a large new chapel next to the old one on 300 North (the old barracks chapel is extant, but not recognizable). Around the same time the parish purchased the old 16th Ward meetinghouse when it was no longer needed by the LDS Church, and established the Guadalupe Center, an educational community center known as La Hacienda, which served the area for many years. The neighborhood has attracted other religious, ethnic and cultural communities. The 29th Ward (just outside the boundaries of the district) was converted to the Hope Refugee Friendship Center. Chiefly serving Vietnamese, the center offered aid to Laotian, Hmong, and Cambodian refugees. Vietnamese immigrants built a Buddhist Temple at 469 North 700 West. Today the neighborhood is one of the most ethically diverse in Salt Lake City.

Despite diversity, the neighborhood has strong communal ties. The Guadalupe, LDS and numerous newer churches in the area provide a sense of community. This year [2001] in May, the Fairpark Fiesta, a neighborhood carnival was held near Jackson Elementary School, hopefully to become an annual event. Preparations for the Utah State Fair unite the western neighborhoods every September. In the most recent decade, new construction of single-family dwellings has been encouraged in the district, and there appears to be an upswing in home ownership versus rentals in the area. Perhaps the strongest indication of stability in the district is in the range of residents. From the direct descendants of early Utah pioneers to non-English speaking immigrants of only a few years, most are happy to call this Salt Lake neighborhood home.

Pingback: 578 N Dexter St | JacobBarlow.com

Pingback: 540 N 600 W | JacobBarlow.com

Pingback: 545 W 500 N | JacobBarlow.com

Pingback: 555 W 500 N | JacobBarlow.com