Tags

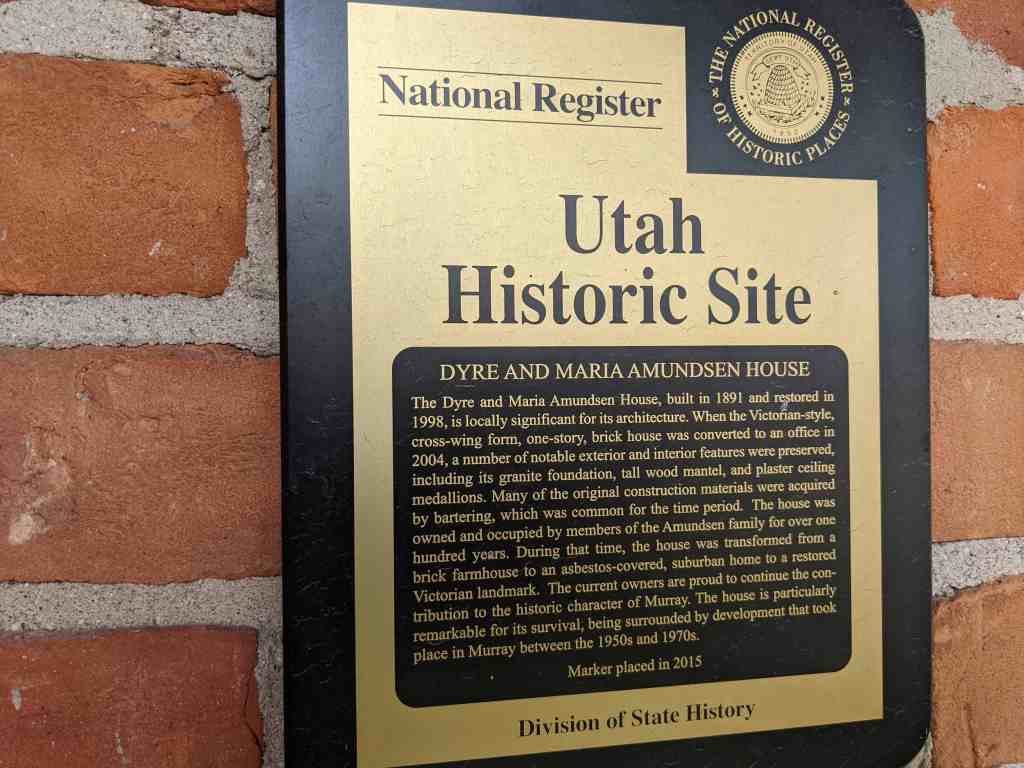

Dyre and Maria Amundsen House

The Dyre and Maria Amundsen House, built in 1891 and restored in 1998, is locally significant for its architecture. When the Victorian-style, cross-wing form, one-story, brick house was converted to an office in 2004, a number of notable exterior and interior features were preserved, including its granite foundation, tall wood mantel, and plaster ceiling medallions. Many of the original construction materials were acquired by bartering, which was common for the time period. The house was owned and occupied by members of the Amundsen family for over one hundred years. During that time, the house was transformed from a brick farmhouse to an asbestos-covered, suburban home to a restored Victorian landmark. The current owners are proud to continue the contribution to the historic character of Murray. The house is particularly remarkable for its survival, being surrounded by development that took place in Murray between the 1950s and 1970s.

Located at 307 East Winchester Street in Murray, Utah and added to the National Historic Register (#15000131) on April 6, 2015.

The Dyre and Maria Amundsen House, built in 1891 and restored in 1998, is locally significant under Criterion C in the area of Architecture. Although the Victorian-style one-story brick house was converted to an office in 2004, a number of notable exterior and interior features have been preserved. These include the granite foundation, a tall wood mantel, and plaster ceiling medallions. The house was owned and occupied by members of the Amundsen family for over one hundred years. During that time, the house was transformed from a brick farmhouse for a major farmstead to an asbestos covered suburban home to a restored Victorian landmark. The house is particularly remarkable for its survival at the edge of an explosion of residential and commercial development that took place in Murray between the 1950s and 1970s. The period of significance dates from the construction of the house in 1891 to the remodeling in 1951. The house is a particularly elaborate early example of a cross-wing Victorian cottage in Murray, especially considering the construction materials were acquired by the barter system common for the time period. The property meets the registration requirements under the Multiple Property Submission, Historic Resources of Murray City, Utah, 1850–1967. The associated historic contexts are “Early Residential and Agricultural Buildings of Murray, 1850-1910” and the “Americanization of Murray’s Residential Architecture, 1902-1965.” The Dyre and Maria Amundsen House has good historic integrity and contributes to the historic character of its Murray neighborhood.

When the Amundsen House was built in 1891 in the Victorian Eclectic style, it did not have the visual complexity of contemporaneous homes in the fashionable urban neighborhoods of Salt Lake City. The house did have a simple elegance that was suited to its rural setting. The unknown builder used a modified cross wing plan and a variety of materials to achieve the visual interest that is characteristic of the Victorian-era domestic architecture in Utah. Dyre Amundsen helped to haul granite blocks for the construction of the Salt Lake City LDS temple and family oral tradition suggests that Amundsen was given permission to select cast-off blocks for personal use. Much of the wood used in the house came from locust trees that Dyre Amundsen planted in the late 1860s or early 1870s. The red and contrasting yellow bricks were likely produced at the local brickyard in Murray. The brick and windows were paid for by a one-acre crop of potatoes. The interior spaces in the south half of the house are larger than the typical house of the period. Family tradition states that Dyre Amundsen received the two large plaster ceiling medallion moldings from the LDS Church as payment for hauling the granite blocks. The brick moldings, granite blocks, ceiling medallions, wide corridors, are atypical for a Victorian-era cross-wing house of the period in Murray.

The Amundsen House as a product of the Victorian period marks a pivotal point in Murray’s history. The availability of kiln-dried brick in the 1860s and the coming of the railroad in the 1870s transformed Murray’s domestic architecture from vernacular buildings to Victorian forms with asymmetrical massing and a variety of texture. The Victorian cottage was the most popular house type in Murray between 1884 and 1910. Dyre and Maria Amundsen originally built an adobe house on their homestead in the late 1860s, then worked many years to afford the spacious brick home that built in 1891. In the post World War-II era, the old brick house may have seemed out-of-date as frame cottages and brick ranch houses were built on the former Amundsen homestead. The family had the house covered with asbestos siding in 1951 effectively suburbanizing it for the next generation. The 1996 to 1998 rehabilitation of the house restored much of the Victorian elegance and was awarded a Utah Heritage Foundation award in 1999.

Dyre Amundsen was born on June 11, 1837, in Gernserud Buskerud, Norway. The family name was Anunsen in Norway. Dyre immigrated to Utah in 1862. While helping to bring other immigrants across the plains in 1863, Dyre Anunsen met and married Beata Erickson, who died in October 1863, only a month after their marriage. Dyre was living in South Cottonwood in 1865 when he met Sophia Maria Person. Maria Person was born in Marna, Sweden, in 1833.2 She immigrated to Utah in 1864.

Dyre and Maria were married in October 1865.3 They lived with the Wheeler family until a small cabin was built for them on Andrew Hammer’s property. Their son, John David, was born in the cabin in December 1867. Dyre Anunsen served in Utah’s Black Hawk War in 1866 and was award a medal for his service. Sometime in 1867 or 1868, Dyre Anunsen claimed a homestead on land along the angled land that would become 6400 South. As a latecomer to the area, his homestead of 160 and 37/100s of an acre was in the shape of an upside down “T” and claimed in three separate parcels. Dyre built a two-room adobe house for his family where a daughter, Sarah Ann, was born in January 1870. A second daughter, Marinda, was born there in April 1873. The adobe house was located west of the later brick house. Dyre was a logger and a farmer. One of the first projects he completed on his homestead was planting a grove of locust trees. The family would later use the wood to build a barn, fences, and the woodwork in the brick house. On February 20, 1875, Dyre Anunsen was granted a land patent for his homestead property.

The Anunsen begin using the name “Amundsen” in the 1880s. In 1891, Dyre filed a deposition with Salt Lake County to change the name on his deeds. The brick house was built in 1891. The builder is unknown, but Dyre himself may have placed the granite foundation blocks that he acquired. The bricks, windows, and other building materials were paid for by an acre of potato crop. The plaster ceiling medallions were reportedly given to Dyre in payment for hauling some of the granite for the Salt Lake temple.4 The Amundsen house and property were at the southern edge of Murray City after annexation in 1905. Dyre Amundsen died on November 17, 1906. He is buried in the Murray Cemetery. At the time of his death, the homestead property had been reduced by more than a half. The land and its water shares were divided between Maria Sophia Amundsen and her three children. Both daughters, Sarah Ann Amundsen Jensen and Marinda Amundsen Boyce, had been married several years and were living in Idaho. In 1909, Maria Amundsen deeded her acreage to her son John David, but retained a life estate. Maria Sophia Amundsen died on August 9, 1918. Her funeral was held in the Grant Ward meetinghouse and she was buried in the Murray Cemetery.

John David Amundsen married Alma Pauline Janson on September 19, 1899. Alma was born in Sweden in 1860 and immigrated to Utah in 1897. On the 1900 census, John David (as David) and Alma are living with his parents, Dyre and Maria. David and Alma had three children: Alice Engre Sophia (born in 1901), Edith Selma Lenora (1903), and Wallace Janson (1906). In a letter describing the history of the house, Edith’s daughter-in-law, Linda Adams, wrote that “the house became two dwellings [Edith’s] parents occupying the three rooms on the West side and her grandparents the two rooms on the East.”5 Edith recalled the driveway was lined with “tall stately poplar trees” and her grandmother had planted the front yard with “yellow roses and Mormon tea vine.” The rest of the yard was planted with “as many shrubs as possible to keep the dust down.”6 David and Alma kept the land as productive as they could, raising vegetable, hay, and sugar beets.

The early settlement of the area began soon after the members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS or Mormon) began arriving in the Salt Lake Valley in 1847. Mormon pioneers quickly spread out from Salt Lake City in search of suitable agricultural land. By 1848 a settlement in the area later known as Murray was established eight miles south of Salt Lake City. The settlement was first called South Cottonwood and was a community of scattered farmsteads originally extending from the Big Cottonwood Creek to the southern end of the Salt Lake Valley, east to the Wasatch Mountains, and west to the Jordan River. As more settlements were established in the south valley, the name South Cottonwood was retained by a group of farmers organized as the South Cottonwood Ward of the LDS Church. An adobe meetinghouse, located at the corner of Vine Street and 5600 South, was the community center for the group. The main north-south corridor was the Territorial Road (later State Street). The Salt Lake City & Jordan Canal and the East Jordan Canal were dug to bring water from the Big and Little Cottonwood Creeks to the farmsteads between South Cottonwood and the settlement of Union to the southeast.

The north half of the South Cottonwood did not remain rural. At the west end Vine Street, an industrial and commercial center began to grow in response to several smelters that were established near the railroad lines west of State Street in the early 1870s. In 1883, the name Murray (after the territorial governor, Eli Murray) was adopted for the town’s official postal designation. The name Murray became official during the incorporation of the city in 1903. At the time of incorporation the boundaries of the city extended from approximately 4500 South to 5600 South, and 900 East to 900 West. In 1905, the city boundaries were extended south to include both sides of 6400 South, which was the main east-west corridor and marked the south boundary of the historic South Cottonwood community.

During the first half of the twentieth-century, Murray City was an industrial town with its own power plant, water system, and school district. Residential development took place near the city center or along the major transportation routes, while the outlying areas continued as farmland. After the last remaining smelter closed in 1950, Murray City with its stable infrastructure and centralized location experienced a post-war suburban building boom. The population jumped from 5,740 in 1940 to 21,206 in 1970. Between 1946 and 1967, sixty seven subdivisions of mostly single-family ranch houses were platted within the boundaries of Murray City. In 1972, commercial property along State Street between 6100 and 6400 South was consolidated for the construction of the Fashion Place Mall. The opening of the mall was planned to coincide with the construction of the Interstate-215 belt route just south of 6400 South. Since the 1970s, the commercial development around the mall has spread along 6400 South east to 900 East. Only a few historic homes, such as the Dyre and Maria Amundsen House, remain to tell the story of the neighborhood’s agricultural past

The census indicates all three grown children were living at home in 1930. Alice worked as a stenographer, Edith was a saleslady for a dry goods store, and David and Wallace worked the farm. David deeded approximately eleven acres in the north half of the property to Wallace in 1931. Alice Amundsen died of influenza in May 1933. One month later, Edith Amundsen married Bronson Adams. Bronson Howard Adams was born in Beaver, Utah, in 1908. Bronson and Edith moved away for a short time, but returned to live at the Amundsen House in 1934. It would be the only time in her life that Edith did not live in the family house on 6400 South. Alma Pauline Janson Amundsen died in February 1936. John David Amundsen died in December 1939. That year, Wallace Amundsen, who remained a bachelor, gave Edith his share of the property with the family home. Wallace Amundsen was living with Edith’s family on the 1940 census, but later moved to an adjacent home at 353 E. 6400 South. He died in 1979.

Edith and Bronson Adams had three children, Kathleen, Patricia, and Howard. Bronson worked in sales and as a warehouseman before starting a career with the Union Pacific Railroad. In July 1949, Bronson Howard Adams died during an operation at the age of forty. In order to care for her family and pay the taxes, Edith sold off much of the family property by the mid-1950s. The covering of the brick house in asbestos shingles in 1951 occurred just after the first postwar subdivision in the south half of Murray was developed between 1946 and 1950. Two of the largest subdivision developments in Murray, Murray Dale and the Murray Dale Addition, were platted in 1953 and 1954, north and east of the Amundsen house on land that was formerly part of the Amundsen farmstead. Edith Adams graduated from the Salt Lake Business School and worked for the Frank Edward Company until her retirement in 1970. When she passed away on October 15, 1995, she was recognized as a lifelong resident of Murray. After her death, her son Howard and his wife Linda, restored the family home. They were assisted by Dan Lossee, a local architect. The home was rented intermittently by family members and others before being sold to Tamra Lee, the owner of the Mt. Olympus Title Company in 2004.9 Although a busy title company office, the house maintains its domestic charm.

Narrative Description

The original footprint of the Amundsen House is a rectangle of 40 feet by 26 feet with a six-foot projecting wing at the southwest corner. The foundation is made from large rock-faced granite blocks. The red brick is laid in a common (American) bond with headers every seventh course. The mortar joints are flush and are a contrasting light tan. There is plain wooden frieze (painted tan) under the eaves. The west projecting wing has a hipped roof. The main wing runs west to east with a simple gable that has been extended to the north. The bell cast extension of the roof above the front porch was made during the 1998 renovations. The wood shingles were installed at the same time. The south projection has two narrow Victorian windows with ornamental drip hood moldings of segmented and corbelled brick in a contrasting tan color. The sills are corbelled rowlock brick. The moldings and the original wood sills were damaged and replaced in 1998.

The current wood windows were installed in 1998, but are similar to the original one-over-one, double-hung windows, which were too damaged to repair. The west elevation has three openings with similar windows with a pair in the center. The treatment of the front door and two windows on the main wing’s façade are the same. The half-glass front door with transom is original, although the glass has been replaced with decorative leadedglass. The front porch is the only major modification to the façade. It is full width rather than the entrance-only porch of the original and wraps around the east side to the bay addition. The new Victorian-style porch features a concrete base with a wood plank deck. The slender lathe-turned posts and balustrade were installed in 1998, but are compatible with the Victorian-style.

The north half of the house was slightly lower and set back on the east elevation. Tax records indicate that by the late 1930s, the house had a 9 feet by 14 feet lean-to addition and a 5 by 7 feet screened porch on the rear elevation. The original east elevation had two windows, one in the taller south half and one in the shorter north half. The rear porch was enclosed and expanded around 1951 when the entire house was clad in pink asbestos siding. The 1951 remodeling included wood surrounds for each opening and wrought-iron supports over the front stoop. In 1996, the siding was removed. The rehabilitation of the house was completed in 1998 including installing a new roof, cleaning the brick, and installing the replacement wood windows. The brick chimney at the center of the house was originally much taller with a corbelled cap. In 1951, it was shortened, but is still operable. A compatible brick addition on a concrete foundation was designed to replace the rear lean-to and enclosed porch addition. A new bay window has altered the historic footprint along the east elevation. The addition matches the details on the original house, but can be distinguished by the use of newer materials.

On the interior, the Amundsen House has 1,844 square feet of space on the main floor. The house has no basement or cellar. The attic space is not useable. The interior features an unusually wide central passage and 12-foot-high ceilings. The parlor to the west features the original carved wood mantel with a mirror inset. The hearth and firebox was replaced with stone tile in 1998. Other original woodwork such as the fluted and paterae window casings and the tall baseboards are intact. The ornamental plaster ceiling medallions in the parlor and living room are original, but the light fixtures are period antiques that were obtained from the Hotel Utah in Salt Lake City. Behind the parlor is the original home’s only bedroom (closet added in 1998). The kitchen is north of the living room on the east side of the house. The east projection, built in 1998, is a conference room. The wallpaper was selected to match the original as seen in family photographs. The French doors and newer woodwork match the style of the original features. The bathroom at the north end of the hall was moved to the east, to provide access for the rear addition. The addition features two rooms and a central bathroom. The spaces have been used for offices since 2004; however, the house could be returned to residential use.

The current 0.53 acre site is only a fraction of the original 160-acre homestead. The unusual shape of the parcel is partially a result of a number of factors: subdivision development to the north, substation expansion to the west, and the busy Winchester Street (6400 South) and Fashion Boulevard intersection, which leads to the Interstate-215 interchange. The driveway originally accessed 6400 South, but was reconfigured in 1998 to provide access from 300 East. The contributing 1930 frame one-car garage is located northeast of the house.1 The space between the concrete driveway and 6400 South is landscaped with evergreens and bark. There is lawn on three sides of the house. There is a large vegetable garden plot in the northeast portion of the lot. Fencing is a combination of brick pier, white vinyl, and chain link.

The immediate neighborhood is a mix of large-scale commercial and single-family residential. The Fashion Place Mall (1972) is directly west of the substation and commercial development has spread along the south side of Winchester Street. On the north side of Winchester Street are historic homes, mostly from the 1940s. The neighborhood north and east of the Amundsen property is a subdivision that was developed in the mid to late 1950s. The original setting of the house has been somewhat compromised by later development, but the house has integrity of location. Minor alterations were made to the design and materials of house in 1998, but the house retains high integrity in terms of workmanship, feeling, and association of the original Victorian-style brick house. Because of its surroundings, the restored Dyre and Maria Amundsen House is a distinctive landmark and a contributing resource in its south Murray neighborhood.