Ogden’s Central Bench Historic District

Ogden’s Central Bench Historic District is the area from 20th Street to 30th Street and from Adams Avenue to Harrison Boulevard in Ogden, Utah.

Previously Listed National Listings, Jefferson Avenue Register/Contributing Properties Within District Boundaries (Individual District, Eccles District, Three-Story Apartment Listings):

- 2461 Adams Ave – Perry Apartments – 1909

- 2509 Adams Ave – Leroy & Myrtle Banks Eccles House – 1917

- 2522 Adams Ave – John Shannon & Louisa Curtis Houtz House – 1910

- 2529 Adams Ave – Mr. J. M. & Mrs. Otis Canse House – 1914

- 2532 Adams Ave – William & Wilhelmine Green/Sherman House – 1914

- 2533 Adams Ave – William & Bertha Eccles/Morrell Wright House – 1911

- 2540 Adams Ave – Edmund Orson & Martha Bybee Wattis House – 1914

- 2545 Adams Ave – Leroy/Larkin, Elijah A. & Rosella Eccles House – 1911

- 2555 Adams Ave – Dr. Hugh & Vern Tavey Rowe House – 1912

- 2565 Adams Ave – Marriner Adams & Dorothea Browning House – 1914

- 2579 Adams Ave – Fern Apartments – 1923

- 2580 Adams Ave – Patrick & Jr. & Mary Sodwick Healy House – 1920

- 2509 Eccles Ave – LeRoy Eccles Home

- 2522 Eccles Ave – John Shannon Houtz Home

- 2529 Eccles Ave – James M. Canse/Ottis Weeks Home

- 2532 Eccles Ave – Virginia Houtz Green/William H. Shearman Home

- 2533 Eccles Ave – William Wright/Joseph Morrell Home

- 2540 Eccles Ave – Edmund Orson Wattis Home

- 2545 Eccles Ave – Elijah Larkin Home

- 2555 Eccles Ave – Hugh M. Rowe Home

- 2565 Eccles Ave – Marriner A. Browning Home

- 2508 Jackson Ave – Royal & Cleone Eccles House – 1924

- 2513 Jackson Ave – J. Willard Marriott House – 1927

- 2529 Jackson Ave – 1911

- 2536 Jackson Ave – Clarence C. Hetzel House – 1915

- 2540 Jackson Ave – 1926

- 2541 Jackson Ave – 1955

- 2548 Jackson Ave – 1924

- 2553 Jackson Ave – 1922

- 2554 Jackson Ave – 1925

- 2557 Jackson Ave – 1926

- 2560 Jackson Ave – 1924

- 2563 Jackson Ave – 1918

- 2567 Jackson Ave – 1922

- 2575 Jackson Ave – 1927

- 2248 Jefferson Ave – Helms Apartments – 1920

- 2300 Jefferson Ave – Upton Apartments – 1925

- 2519 Jefferson Ave – First Baptist Church – 1923

- 2520 Jefferson Ave – Thomas H. Carr House – 1910

- 2523 Jefferson Ave – Edmund T. Hulanski House – 1891

- 2532 Jefferson Ave – Thomas A. Whalen House – 1889

- 2539 Jefferson Ave – Farnsworth Apartments – 1922

- 2540 Jefferson Ave – Hill / Hoxer House – 1889

- 2546 Jefferson Ave – Fred M. Nye House – 1910

- 2554 Jefferson Ave – Boreman Hurlbut House – 1889

- 2555 Jefferson Ave – Spencer Eccles House – 1895

- 2560 Jefferson Ave – John G. Tyler House – 1891

- 2575 Jefferson Ave – Thomas Jordan Stevens House – 1891

- 2580 Jefferson Ave – Bertha Eccles House – 1890

- 2604 Jefferson Ave – James Pingree House – 1908

- 2606 Jefferson Ave – First Methodist Church – 1928

- 2615 Jefferson Ave – 1906

- 2619 Jefferson Ave – George Halverson House – 1915

- 2627 Jefferson Ave – Richard & Ellen Leek House – 1905

- 2631 Jefferson Ave – Frank A. Baker House – 1890

- 2640 Jefferson Ave – Emil & Emma Bratz House – 1903

- 2646 Jefferson Ave – 1908

- 2656 Jefferson Ave – Thomas Beason House – 1910

- 2659 Jefferson Ave – 1910

- 2660 Jefferson Ave – Alfred Meek House – 1890

- 2663 Jefferson Ave – 1900

- 2668 Jefferson Ave – William Scott House – 1890

- 2670 Jefferson Ave – B. G. & R. C. Nye Blackman House – 1891

- 2671 Jefferson Ave – William “Coin” Harvey House – 1891

- 2683 Jefferson Ave – John & Amy Corlew House – 1903

- 2687 Jefferson Ave – 1910

- 2418 Madison Ave – Madison School – 1890

- 2622 Madison Ave – John Dalton House – 1890

- 2681 Madison Ave – Flowers Apartments – 1923

- 2465 Monroe Blvd – Fontenelle Apartments – 1924

- 2485 Monroe Blvd – Hillcrest Apartments – 1923

- 2408 Van Buren Ave – Gustav Becker House – 1915

- 2432 Van Buren Ave – Elmhurst Apartments – 1929

- 2507 Van Buren Ave – 1925

- 2516 Van Buren Ave – 1905

- 2524 Van Buren Ave – Witherell House – 1889

- 2527 Van Buren Ave – Dr. Ezekiel R. & Edna Wattis Dumke House – 1917

- 2538 Van Buren Ave – Earl E. & Elizabeth E. Greenwell House – 1919

- 2541 Van Buren Ave – Ruth W. & Marriner S. Eccles Gwilliam House – 1917

- 2544 Van Buren Ave – 1905

- 2547 Van Buren Ave – Peter D. & Helen I. Kline House – 1913

- 2550 Van Buren Ave – 1885

- 2553 Van Buren Ave – 1921

- 2558 Van Buren Ave – “Taylor Made” Apartments – 1927

- 2559 Van Buren Ave – 1924

- 2571 Van Buren Ave – 1929

- 823 23rd St – Arvondor Apartments – 1925

- 795 24th St – Heber Scowcroft House – 1925

- 549 25th St – Don Maguire Duplex – 1891

- 607 25th St – David Eccles House – 1904

- 635 25th St – Dennis Smyth House – 1889

- 726 25th St – Andrew Warner House – 1890

- 802 25th St – McGregor Apartments – 1924

- 961 25th St – Avon Apartments – 1908

- 583 26th St – Amos & Eva Corey House – 1884

- 670 26th St – Ladywood Apartments – 1926

- 461 27th St – La Frantz Apartments – 1920

- 505 27th St – John Browning House – 1900

- 579 27th St – Fairview Apartments – 1916

The Central Bench Historic District is significant under both Criteria A and C. Under Criterion A, the district is significant as Ogden’s largest historic residential neighborhood, with a period of historical significance dating from 1877 to 1954. The buildings reflect the transition of Ogden’s residential neighborhoods as the city emerged from its agricultural beginnings to become a major center for government, commerce, education, and industry. Prominent families involved in local, state, and national affairs all made the Central Bench Historic District their home. Although the district is primarily residential in nature, it also includes an institution of higher learning, several religious facilities, and various commercial buildings. Because of the diversity of uses, historically the neighborhood was self sustaining, further differentiating it from the industrial/commercial sector of town. Under Criterion C the district is architecturally significant for the diversity and integrity of the buildings. The district contains the best concentration in the city of examples of historic styles and types that were popular both in Ogden and throughout Utah. The houses range from early vernacular Classical style to high-style Victorian architecture to more modest bungalow, period revival, and post World War II styles. The historical and architectural diversity in the neighborhood, along with the high concentration (73%) of well preserved, contributing historic buildings makes the Central Bench Historic District the most important historical neighborhood in the city of Ogden.

Early Development and Structures: 1870s to 1887

Exploration and Settlement

The first European-American settler of Ogden, Miles Goodyear, built a fur trading post in 1845 on an attractive spot of the Weber River, not far from where the Weber and Ogden Rivers converge. In 1847 he sold the property to Captain James Brown, a one-time leader of the Mormon Battalion. Soon after, numerous Mormon families started to migrate to the area. In 1850 Brigham Young, President of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, established the basic plan for the city. More Mormon families were sent to settle the area, and in 1851 Deseret incorporated the city of Ogden, with Lorin Farr being called to serve as its first mayor. Later in 1851, Henry Sherwood surveyed the streets, blocks, and lots as planned by Brigham Young. An early Ogden journalist noted, “Those who planned the future of Ogden intended that the city should be a mile square; that they made the blocks to contain 10 acres, divided into 10 lots of one acre each; the blocks were 660 feet square and the streets were 99 feet wide excepting Main Street (Washington Boulevard) which was 132 feet wide; the first plat provided for 56 blocks, arranged in seven rows of eight blocks each.” A large portion of that original plat included part of the Central Bench Historic District, the area between 21st and 28th Streets and Adams and Madison Avenue, approximately one-third of the district. Originally, the streets in the district were given names other than United States Presidents. Starting at the western boundary of the district moving eastward the streets were titled Spring (Adams), Smith (Jefferson), Pearl (Madison), Green (Monroe), East (Quincy), 1st East (Jackson), and 2nd East (Van Buren). The streets that ran east to west have also been changed. Twenty blocks were added to its original development, and for instance 1st Street and 4th Street are now known as 21st Street and 24th Street, with twenty blocks added northward to its original development.

Ogden Valley’s geographical make-up played an important role in the early settlement of the city and subsequent development in the Central Bench District. On the eastern border of Ogden lies the Wasatch Mountain Range, with the Weber and Ogden Rivers flowing through it and emptying into the Great Salt Lake, lying just west of the city. In the early 1850s as Mormon families began to move to Ogden in large numbers, the most desirable land was that which was located between the two rivers in the northwest corner of town, with its rich soil and easy irrigation. A good portion of the area was surveyed into farming tracts and large numbers of people settled portions of the riverbanks. By the mid-1850s this desirable portion of town was largely populated and the community started to look eastward for expansion. And in 1855, under the direction of Isaac N. Goodale, appointed by Brigham Young, construction of the Ogden Bench Canal had begun. Canals and irrigation ditches were a common feature in almost all Mormon platted towns.

The building of the canal was an important endeavor, as an editorial in the Ogden-Standard Examiner stated in 1945, “The story of the Ogden Bench Canal is pretty much the history of early Ogden.” The purpose of the canal was to use the canyon streams east of Ogden to provide irrigation to the bench area in order to sustain the newly developing community. Running north to south the canal flowed from the northern tier of the city (at the time 21st Street) to the southernmost boundary (28th Street), and from east to west it cut through just below 2nd East (Van Buren Avenue) and ended up near Green Street (Monroe Boulevard). Another important early canal was the Weber Canal. Although it did not run through much of the district (it only ran through the area of the 2800 and 2900 block of Porter Avenue (a half-block between Adams and Jefferson Avenues) and left the district westward on 28th Street) it did give the Boyle family, who resided between Adams and Jefferson Avenues on 28th Street, power to run tools to make their patented furniture. The curved street between 28th and 29th Streets on Porter Avenue is a good reminder of the canal; when the block was subdivided in the early 1900s the street was graded following the crooked path of the canal.

Community Development and Planning

By 1860 limited building and settlement had started to take place in the district. A Deseret News article described the gradual movement of families to the area in 1863, “A few of the settlers, preferring to dwell on more sightly [sic] ground and where the streets, with slight grading, would be passable most of the year, have located themselves on the upland, or bench, as it is usually called, where the houses generally, as in further witness of their good taste, if not superior judgment, are of a neat and comfortable appearance and, so far as I could learn, fully occupied by an eminently practical and enterprising class of citizens.” The term “bench” was fittingly designated early on for the area because of its unique geographical position to the rest of the city, lying on a small hill looking down on the rest of Ogden.

Throughout the 1860s development was gradual and persistent in Ogden and in the bench neighborhood; by the end of the decade Ogden’s population had grown to 3,000, from 1,500 in 1860. Then in 1869 the Union Pacific Railroad Company completed the railroad through Ogden, and after the transcontinental connection was made at Promontory, Utah, it was agreed that Ogden was the ideal intersection for the east-west railroads. It was more difficult for the railroad companies to decide where the intersection for the north-south railroad would be located, as Corinne, located 15 miles northwest of Ogden, was better geographically located. However, after Brigham Young promoted Ogden by deeding 131 acres of land to the Union Pacific and Central Pacific, the decision was made to make the city the hub of the north-south lines. Ogden soon became the “Junction City” of the Intermountain West.

The early impact of the railroad was significant, however in the beginning it did not change the face of the Central Bench immensely. In an 1875 reproduction of Ogden, a bird’s eye view of the district shows a sparsely developed community with only a few structures located on each block. One of the earliest homes remaining in the district was constructed during this era. The Hathron Chauncey Hadlock House, c. 1877, is located at 478 28th Street.

Other kinds of development started to take place in the district as the bench area started to solidify itself as a key residential sector of the city. A good example of that is found at Liberty Square (now Lester Park). The tree-lined park, located at 25th Street and Jefferson Avenue, was initiated for public use in 1870, and soon became a popular meeting place for religious groups, political organizations, school functions, parties, and other. activities. One decade later, as it became an important gathering place, a large drinking fountain and dance pavilion was added to the park.

During the 1880s, as Ogden’s population continued to grow in larger numbers due largely to the impact of the railroad, the Central Bench remained to be a predominantly rural community. A well-preserved example of the rural folk house of this period of time is the small picturesque cottage located at 937 22nd Street, constructed by local builder Henry Ware in 1887. The John F. Gay House, located at 2121 Adams Avenue, is another notable home constructed during this era. Mr. Gay was a Utah pioneer of 1851 and was a lieutenant in the Utah Black Hawk War in Manti in 1865. He came to Ogden in the late 1860s and commissioned William W. Fife to design and build this large Gothic Revival style residence in 1885.

According to Olivia Gay, J.F. Gay’s daughter, the home was the first residential structure in the city to be built and designed by an architect. In fact, the 1880s is when Ogden first started to witness a number of buildings being erected by architects.

Architecture

Early Architects/Builders

William W. Fife is the most noted early professional architect in Ogden; prior to this era in Ogden and Utah in general the housing design at the local level was usually the responsibility of the person in the building trade. As an architect Mr. Fife designed several early structures in the district, as was the case with the Gay House. Mr. Fife was born in Ogden in 1856. His father, William Nicol Fife, was a well-known builder and contractor from whom W.W. Fife received his training at a very young age. While just a teenager, W.W. Fife helped run his father’s business. And although W.W. Fife died in his fortieth year, his accomplishments in the building of the city were second to none. Mr. Fife also resided in the district at 2122 Adams Avenue, building the Vernacular-Classical style hall-parlor family home c. 1885. In addition to William N. and William W. Fife, some other early builders in the district include D.D. Jones, who was also listed as an architect in the late 1880s. Henry Mortensen, who resided and ran the family business M.F. Mortenson and Sons in the district, lived just above Madison Avenue on 23rd Street. Nils C. Flygare, who was a contractor, resided in the district on 24th Street just above Monroe Boulevard.

To supply the aforementioned builders and other early settlers in constructing their homes, several industries were established. Ogden’s first Mayor, Lorin Farr, was instructed by Brigham Young to build a sawmill and gristmill, which were established as early as 1851 to aid the Ogden pioneers. Ogden Canyon was the early settler’s favorite location to collect timber for construction of their homes. A sawmill was later placed in the canyon, and other mills were also placed elsewhere throughout the city. Adobe supplemented lumber in Ogden’s early years. A large adobe “hole,” where adobe was made, could be found lying east of the cemetery and just across from the northern boundary of the Central Bench District; undoubtedly this is the location where several of the early home’s material in the district were made. Other industries related to building during the 1850s-1880s were also established, such as stone quarries, limekilns, brick kilns, carpentry, plumbing, painting, and tinsmithing. The materials needed for home building was made possible for early builders, by the early Ogden settlers, and everything could be found within the city; and by the late-1880s materials became even more available due to the advent of the railroad in Ogden City.

Subdivisions

Another new development in the 1880s in Ogden was that of subdivisions. As will be seen the proliferation of subdivisions occurred greatly in the very late-1880s, however, Ogden’s first subdivision-Kershaw’s, was platted in 1881 by A.J. Kershaw. Kershaw Avenue was eventually changed to Eccles Avenue in the 1910s, after the development of the Eccles Subdivision, which lies one block south of Kershaw’s.

It is clear that by 1887 the Central Bench had started to establish itself as the dominant residential sector in Ogden. Located on the bench, it was a place where families could move to escape the more bustling and busy area of town west of the district. The bench area slowly became a destination for a wide variety of people, including railroad employees, merchants, laborers, and businessmen. As was noted in a publication of the University of Utah Graduate School of Architecture, “After becoming a railroad hub in the 1870s and 1880s, Ogden slowly developed something of a split personality. A schism emerged between the residential and commercial area running east from Washington Boulevard, and the western industrial district, located near the rail yard.” And of the Central Bench they concluded that it was an attractive sector of the city with tree-lined, middle-class neighborhoods and represented stability, refinement, and peacefulness. Indeed, this sentiment of a need for a stable and peaceful neighborhood only grew as Ogden was approaching a new, more rapidly changing turn to greater growth and development.

A good percentage of the homes that were built pre-1887 in the neighborhood have been razed, with most demolished by the end of the 1920s to make room for more modern houses. Also, during the early days of the Central Bench, most families initially settled on large parcels of land and built smaller adobe and wood frame houses, usually with a stable and/or a barn in the rear of the property. As many of these Ogden pioneering families grew in size by the turn of the century, so would the need to increase the size of the home. So, many demolished their original dwelling and constructed a new home on the site or kept the old dwelling for a while and built new structures on their surrounding property, sometimes building homes for their children. William G. Biddle and family, of 2447 Monroe Boulevard, is a good example of this process.

The Biddles, Mormon pioneers, trekked to Utah in the early 1860s and by 1870 had settled on an acre of land in Ogden, located on the 2400 block of Monroe Boulevard (Green Street). They built a small rectangular shaped wood frame home on the north end of the lot. Two decades later the Biddies demolished this home and built a more modern Victorian Queen Anne style dwelling at 2447 Monroe on the south half of the lot; after demolishing the old home and building the new, the Biddies then sold the north half of their lot. Many other residents would simply build their home in the rear of the lot and years down the road build a modern home closer to the street front.

Another factor that changed the older face of the district during the building and population boom that was to come during 1888-1892, was that many families started to subdivide lots to help provide land and make profit during the boom, and their old property was systematically absorbed by Ogden’s expansion. Replacement homes were very common in the district, old homes being demolished and replaced by newer homes on the original home’s site. The years prior to 1888 were a time of settlement and growth for the district and helped set up what was to become one of the largest 5-year spans of growth in the district and city’s history.

Growth, Prosperity, and the Changing Face of the District, 1888-1899

Social History

The district is important in that it portrays the development of civic life during the late-1800s, serving as the main residential neighborhood in the entire county. This could be seen during that era as people, ranging from blue collar workers to businessmen, flocked to the area.

Ogden’s “Boom” and Sudden Popularity

In the early months of 1888 the Ogden Semi-Weekly Standard started to pay particular attention to a rather peculiar demand for rental housing in the city. In the past, several houses in the city had been built for the sole purpose of renting. The homes were constructed in numbers to more than meet the demand of renters coming to Ogden, and were offered at a reasonable price. However, by early-1888, homes that were easily procured at the renters own price in 1887, could hardly be attained now at any figure. As one gentleman residing in Ogden remarked, “There had probably never been so great a demand for rentable houses as there is at the present.” It was mentioned that the “Junction City” was starting to enjoy a season of prosperity that was causing the citizens to enjoy the highest satisfaction, and to look forward to the future with a renewed energy. Although Ogden had seen considerable growth since the railroad’s arrival in 1869, no one was likely prepared for the boom that lay directly ahead.

It was suggested that investors with the means start to put money into building well-appointed tenement houses. Soon, talk of construction for the upcoming summer months was underway. In addition to the many public institutions that were projected, the building of residences was highly discussed, particularly in the Central Bench District. It was in the hope that the new homes would provide for the many who were moving to Ogden to work for railroad related businesses, create jobs for the unemployed, and add to the appearance of the city which had started to be more recognized. Realizing the possibility of a real estate boom, investors started to take notice of the city. In February a timely article in the Ogden Standard was published forewarning Ogden citizens of the upcoming real estate boom. It was emphasized that individuals who had a homestead or owned a tract of land not feel entitled to sell it. It was also suggested that people not get caught up in buying land for speculative purposes in order to not drive away those interested in Ogden, and so those who wanted to buy land to build on could do so affordably.

Several factors, over and above being the railroad hub of the intermountain West, played into the attention Ogden starting receiving in 1888. Mr. Alfred H. Nelson, proprietor of the Weber County abstracts and an old time realtor of Seattle during its boom days, who came to Ogden in 1883 because of the potential he seen of it becoming a robust city, was quoted as saying, “The only wonder is that the attention of Ogden has been so long delayed, as no other city in the West equals it as a railway and commercial center.” Moreover he claimed, “The attractions of Ogden are manifold, and no one article could do it justice.” He went on to discuss Ogden’s importance as a commercial and manufacturing center, the high quality of land and easiness to obtain the lands as land titles in Ogden were the most accurate he had ever seen, Ogden’s geographical location in terms of its proximity to the Great Salt Lake and beautiful Wasatch Mountains, and best of all its climate. His explanation for Ogden being overlooked in the past was the fact that Salt Lake City had been synonymous to Utah, and consequently the only place people came to stay or visit.

Mr. Nelson did have faith in the city, as can be seen by the several residences he built here, particularly in the Central Bench District. A good example is the Victorian style central block with bays home he had built at 506 23rd Street, which was used throughout most of its history as a rental unit. Many others had respectable views of the city. A visitor of the city remarked, “There is no place but Ogden for me, I like the broad progressive liberal-mindedness of her citizens, I adore the sociability which is to found within her borders, and the activity which characterizes her.

In light of the increasing “buzz” about Ogden, builders and contractors were looking forward to the largest building season they had experienced in years. This perception was no understatement. Numerous homes were constructed during 1888. The availability and ability to obtain products such as lumber and brick were made possible through the railroad, and labor was readily at hand as many moved to the city to work. By April of 1888 the largest brick factory west of St. Louis was located in Ogden , within the Central Bench District between Madison and Jefferson Avenues and 28th and 29th Streets (demolished). Doubtless, a good percentage of the homes that are still standing in the district from this boom era were constructed using the brick of the plant. By the end of 1888, the foundation had been laid in order to bring in another prosperous year and the outlook in the beginning 1889 was that it was to be the best year Ogden had ever had in terms of business, growth, and building.

One of the interesting developments in 1889 was the increasing attention the city was receiving by people who lived outside of Utah. The Denver and Rio Grande Western, along with the Union Pacific, started taking investors, developers, etc. from Denver to Ogden in March of 1889. The excursions were advertised in newspapers in nearby places such as Colorado, and articles were published in the Ogden Standard to make citizens aware and urged the community to take their part in welcoming the visitors and making sure their stay was a pleasant one-to showcase Ogden in the best possible light. In fact, many Ogdenites took this to heart. When one Ogdenite was asked by an excursionist from back east what he thought of Ogden, the citizen replied, “I think it is the best city in the this part of the country and if I had $50,000 to invest, I would invest it all in this city.” Needless to say, this type of response was common and made the city even more enticing.

To boost the city even more, in conjunction with Salt Lake City, the Chambers of Commerce gathered the lilacs that bloomed during the spring in Ogden and loaded them into a Denver and Rio Grande Western railcar; as the train headed eastward to Colorado a number of boosters handling the lilacs made them into small bunches suitable for boutonnieres and bouquets. Colorado responded, at every station where the train stopped there was a crowd of people asking, “Which is the lilac car?” Colorado was not the only state moved by the boom that was occurring in Ogden. People, such as C.D. Hammond all the way from New York, made their way to Ogden to invest in Ogden property. By now, the boom was now well underway. For instance, in a single day in April over $180,000 changed hands over property. Several individuals from places such as Denver, Boulder and Fort Collins, Colorado; Paola, Kansas; and Syracuse, New York, all were shown making investments on OQ that one day. Real estate investors alone were not the only people coming to Ogden. Builders, architects, and contractors were moving to the city in large numbers. The same was true for businessmen and others looking to put themselves in a better position. The people who came to Ogden quickly saw the bench area was the place of choice to settle, as the division line that had started to separate the residential district from the rest of the town before 1888 took form during the boom years.

Most of the newcomers who made their way to Ogden during 1889 made their new homes in the Central Bench District. Architects John Collins (home and office located at 2670 Jackson Avenue), Francis C. Woods (he built the Catholic Church at 506 24th Street and Madison School at 2418 Madison Avenue), George A. d’Hemcourt (resided at 874 23rd Street), and Charles J. Humphris (he designed the homes at 2605 Jackson Avenue) all made the Central Bench their home.

Businessmen and entrepreneurs were also attracted to the Central Bench. The hope of becoming wealthy lured them to Ogden, and the peacefulness of the highly expanding bench neighborhood led them to build a home and reside there. Fred Morgan Nye is a good example. He was born and raised in Eureka, Kansas, and received his higher education at Beloit College in Wisconsin, and at Knox College in Illinois. He resided at 2546 Jefferson Avenue. After completing school and hearing the news of Ogden’s boom, he moved to the city to open up a clothing store. Other notable businessmen moving to the district included O.A. Parmley (730 25th Street), S.H. Hendershot (1165 25th Street), James G. Paine (2103 Adams Avenue), and John T. Hurst (2535 Adams Avenue). The individuals aforementioned were not the exception to the rule in 1889, the story was repeated over and over again as Ogden and the Central Bench District expanded. In fact, the increase of total real estate sales in Ogden jumped up from just over 1.2 million in 1888, to over 5.6 million in 1889.

Change and Continued Growth

Liberal politics in Ogden, as opposed to the earlier predominately Mormon operated and run city, were transpiring as well. In 1889 the Liberal party of Ogden reached its pinnacle when every party candidate running for office defeated their rival Mormon People’s party candidates, with Fred J. Kiesel elected to the office of mayor. The following day the Utah Daily Union summed up the election on their headline, “Ogden Americanized.” Several of the party members lived in the bench neighborhood, including Mayor Kiesel, who resided on the corner of 25th and Adams (demolished), and City Recorder John W. McNutt, who resided in an attractive Eastlake Victorian dwelling at 614 24th Street. One of the most noticeable changes the Liberal Party brought about while in office was the changing of the street names in the city. Several of the original names were named after Mormon figures, such as Smith and Young; they were then replaced with the names of the United States Presidents. Not only were the Liberal party members involved in politics, they were also involved in business and most importantly real estate. For instance, in 1888 and 1889, when the city offered lots for sale in Plat C of the city (which approximately makes up the eastern quarter of the Central Bench District), four-fifths of the lots were bought up by Liberal Party members. By 1889, the Mormons and “Gentiles” (as non-Mormons were known locally) clearly started to mesh.

As the bench community’s expansion continued in 1889, the area was not free of problems. In addition to the sanitation and public health issues, in Ogden the question of how to build and how to divide lots and blocks became a key issue. The concern of dividing blocks and lots stemmed from the way the blocks were carved into lots from the original Mormon town plan. Each consecutive block was reversed in the laying out of the lots. For example in one-half of the blocks the lots were twenty rods north and south by eight rods east and west, with the other blocks just the opposite. Narrowing the, streets was also a popular topic of discussion. Many residents thought the streets to be a nuisance and that the cow-pasture and hay-wagon period had passed, thus the large streets were no longer needed. By narrowing the streets, property owners would have more land for their lots, and then sidewalks and roads could be paved with more ease. The construction of the era started to see new styles and better methods used in building. No longer were the shoddy building styles of the past acceptable, and builders were shied away from doing so, and according to a local newspaper, “They should be absolutely prohibited.” Indeed, the new buildings were constructed using better materials and craftsmanship never before seen in the city, and the hundreds of well-built Victorian homes remaining today in the district are testament of it.

More of the same continued throughout the end of 1889. Ogden was forging ahead and construction was vigorously underway by the early months of 1890. The population in Ogden was growing immensely, thus creating a pressing need for more housing. At one time the need for housing became so severe a group of men got together and formed a company that set out to import prefabricated homes from St. Paul, Minnesota. The homes were known as “famous” Totman houses, and were to be 1 1/2 stories tall with six bedrooms, costing $1000. At least one of these homes was constructed in the district in July of 1890, just east of Liberty Park.

Architects, builders, and realtors continued to flock to the city in record numbers. In fact, prior to 1888 real estate dealers in the city were very scarce, but by 1891 over 100 dealers could be found within the city. One of the most famous events held in Ogden during its boom days occurred in July of 1890, when Ogden realtor William Hope “Coin” Harvey, along with his fellow boosters the Order of Monte Cristo, tried to promote an economic Mardi Gras in Ogden, calling it the Rocky Mountain Carnival. Through the carnival, although it was not the success Mr. Harvey had hoped, Ogden received national attention and sold its position even more as a significant railroad and manufacturing center in the western United States. The city continued to grow, as did the bench neighborhood, and by 1890 the population in Ogden was up to 12,000. William H. Harvey left Ogden in 1893 to pursue his ambitions in the fight for the coinage of silver and in 1932 ran for the President of the United States under an independent party. While living in Ogden Mr. Harvey, who came to the city in 1888 from West Virginia, resided at 2671 Jefferson Avenue. It was in the atmosphere of the boom in 1890 that several of the residences on Jefferson Avenue were built. The line of homes, particularly between 25th Street and 27th Street, were referred to as “banker’s row,” as many of the people who lived in the area were bank personnel or others involved with the financial affairs of Ogden. The Jefferson Avenue District has previously been placed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Indeed, 1890 marked another record year for Ogden. Ogden more than doubled total sales of real estate from just 5.6 million dollars in 1889 to over 12.1 million dollars in 1890; and in 1891 building and sales increased by an even greater percentage. In that year alone over 50 dwellings were constructed in the district. And in 1892 the district continued to grow. By the end of the boom years, which lasted from 1888-1892, Ogden had grown and prospered quickly; the city went from a more rural community with a thriving industry, to a full urban commercial and manufacturing center with an attractive residential neighborhood. There had been steady and continuous growth in commerce, manufacturing, agriculture, mining, railroading, building, and in all sorts of other industries, most doubling to quadrupling in size. The Central Bench neighborhood’s foundation was quickly formed by the rapid development and creation of subdivisions, leaving the street and block pattern primarily how it is found today.

One-half of the district’s twenty-six subdivisions were developed over these five years. Bichsel’s, Capitol Block, Chamberlin’s, Corey’s, Dankowske’s, Dundee Place, Maguire’s, Moffit’s, Park Place, Rider’s, and Rushton Subdivision were all developed during the boom years. Realtors and investors of Ogden City developed many, and several were created by out-of-townsmen. Investors outside of Utah included, among many others, Hiram C. Rider (Rider’s Subdivision) from Denver, William F. Thompson and James C. Scott (Rushton Addition) also from Denver, arid Ronnie and Rose Moffit (Moffit’s Subdivision) from Wyoming.

The phenomenon of non-Ogden investors in the city may have started during this era, but it continued on throughout the later development of city. For instance in 1915, 1600 people from outside of Utah were listed as owners of Ogden real estate, with 400 of those residents from Colorado. Maguire’s Addition was developed by Don Maguire, a Vermont native who was highly educated, a writer, geologist, businessman, builder, and scientist, developed a subdivision then attempted to sell his individual lots to people from out of state. One advertisement placed in the newspaper states, “Attention Excursionists, we will sell for five days only, two or more lots in Maguire’s addition for $150.00 per pair.” People from other cities besides Ogden, in Utah invested in Ogden property as well. Reed Smoot, a one-time prominent banker, LDS Church leader, and United States Senator who lived in Salt Lake City and Provo, was a good example. Although Mr. Smoot never developed a subdivision in Ogden, his property holdings in the city were numerous, particularly in the Central Bench District.

The largest of all the subdivisions developed in the district, and one of the largest in the entire city, was the Rushton Addition, which encompassed an area of four blocks in the northeast corner of the district. Though many subdivisions were platted, many were not developed for several decades. The subdivided land planned for use as Ogden’s population grew, particularly on the eastern quarter of the district, never reached full capacity and thus did not require development at the time. Ogden had rapidly descended into an economic , depression. For as the boom was a reflection of a large increase in population, development, and building, and many profited from it, the growth was just that a boom. And as quickly as it came it disappeared even more quickly.

Economic Depression

By 1893 Ogden had sunken into a major economic depression. The Panic of 1893 that had hit the rest of the nation also took its toll on Utah, and especially Ogden. During the Cleveland Depression an unprecedented 15,200 American businesses went into receivership, 18 percent of the national work force did not have a job, and those who remained employed saw their wages cut on an average of 10 percent. Utah was facing a severe winter in January and February, which put a hold on the building in Ogden. Due to this and the economic and financial problems facing the nation, the city never quite regained its strength. Many people lost their homes, and those who moved to the city in hopes of building a home and starting their lives in the city put those plans on hold. A good indicator of the troubling times occurred with a newly built Ogden Hospital (demolished), located on 28th Street between Madison and Monroe Avenues. In 1892 the hospital was constructed at a cost of $25,000, and the following year the hospital had to shut its doors because of a lack of funds. The hospital eventually reopened in 1897, and was the primary Ogden hospital until 1910, when the Dee Memorial Hospital opened.

By mid-1893, builders in Ogden became disillusioned with the city as no effort was being made to keep these industries in town. In frustration one Ogden man explained, “Ogden can’t raise $50,000 to maker her own doors, but she can raise $150,000 every year to buy the doors and sashes made elsewhere; Ogden ought to adopt her motto, ‘Millions for foreign industries, but not a cent for home manufacturers’.” The Ballantyne family recalls the turbulent years of the early-1890s, “It was truly an era of booms and bust, bread lines and soup kitchens sprang up to take care of the unemployed…the Ballantyne Brothers Lumber Company was swallowed up in the national crisis, its receivables became worthless pledges and its inventory values had shrunk to only a fraction of the original cost, and sales dropped so low that the firm could no longer meet its obligations.” By the time the depression was over Richard Ballantyne had lost both of his homes and his company.

It is apparent that building did not altogether stop in the city during the time of depression and discouragement. Some of the leading financial men of the city had first rate residences constructed, taking a stand that they believed the future was bright and they wanted to be a part of that future in Ogden, bringing some sign of hope to the despaired community. A good example of the homes built in the district during this time was the Vernacular-Victorian Eclectic style home constructed for George C. Bent, the manager of the Ogden Paint, Oil, and Gas Company. Subsequently, the house, which lies at 2071 Madison Avenue, would later become the home of one-time Weber Stake Academy President and LDS Church President David O. McKay. Despite this and other examples, the boom by all accounts was over. Building throughout the mid-1890s would be much slower than the earlier years of the decade.

Education

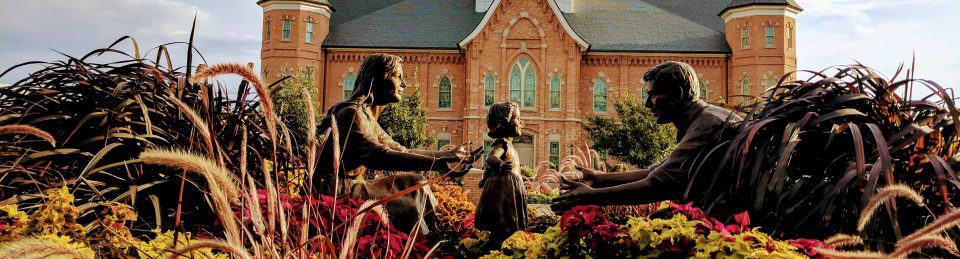

The district is significant in that it was home to one of the largest educational campuses north of Salt Lake City, the Weber Stake Academy (now Weber State University), run by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Its development changed the face of the Central Bench District.

In 1888 the Weber Stake Board of Education was formed, and soon thereafter a small building was designated to be rented for classrooms, and supplies were ordered in order to open up a school. By January of 1889, the school had appointed its principal, Louis F. Moench (who resided in the district at 26th and Jefferson), and classes had begun. Ninety-eight students attended the first semester, and at the beginning of second semester in March enrollment climbed to 137. The first year’s enrollment at the school far exceeded expectations, so during the fall of that year the church secured the Weber Stake Tabernacle in order to make room for the students who wished to attend. In 1890 the school moved its classroom again, to the Fifth Ward Institute building. And finally, in 1892 the school moved to its new and long-time home on Jefferson Avenue between 24th and 25th Street. The academy was officially recognized as a high school in 1895, and in 1916 it was officially recognized as a normal school and raised its rank to a junior college.

In addition to Louis F. Moench, several other presidents of the school resided in the district. Aaron W. Tracy of 2332 Jefferson Avenue, and David O. McKay (later he became President of the LDS Church) of 2071 Madison Avenue are two of the most noted to do so. Several teachers and students also resided in the district. For those students and teachers who did not live in the vicinity, the Ogden Rapid Transit Company offered good rates for round trip fares. Dormitories were also located in the district to help suit students. The most noted dormitory was the Bertha Eccles home located at 2580 Jefferson Avenue, which was used as a women’s residence hall during the 1940s. From its precarious beginnings in the late 1880s the school had its up and downs, but its importance and influence in the district was extraordinary. During the depression years the school made the transition from a church school to a state-run institution, and by the early 1950s due continued growth the school moved from its location in the bench district to its current home on Harrison Boulevard. A good remnant of the school today is the neoclassical style gymnasium, c. 1925, located at 550 25th Street.

As the district developed into the residential hub of the city, several other schools were constructed to meet demand. The most impressive remaining structure of this is the Madison School, located at 2418 Madison Avenue. The emergence of public “free schools” was a long process in Utah and by 1889 the issue heated up in Ogden. After Utah enacted the free school law in 1890, the public school system took off in the city. For instance in 1890-1891, 1600 students attended public schools and by the following year 2853 were listed on the rolls of the schools, and the next year, in 1892-1893, 4,000 were attending public schools in the city. New schools were needed, particularly in the bench neighborhood. During the spring of 1892, plans were displayed for the Madison School, by Francis C. Woods. The large building Was done in the impressive Richardsonian Romanesque style. The school was built on a site that had been the location for an earlier school, known as the Fifth Ward School, the Fifth Ward School was typical of the earlier schools in the bench district in that it was built in the late-1870s and was a small, one or two classroorn, adobe or wood frame building. In addition to the Madison School and Weber Academy other schools built in the district during this boom era include the Sacred Heart Academy and the Quincy School (both demolished). The Madison School building has since been adapted into apartment use.

Architecture

The architecture of the boom years was quintessential Victorian. The popular styles during the Victorian era, the era in America during the closing decades of the nineteenth century, epitomized the self-confident optimism of that time period. The dwellings were a physical embodiment of prosperity. The Central Bench District is home to various Victorian era styles, hundreds of which remain from the boom years between 1888 and 1892. Two of the best-known styles of the period include the Eastlake and Queen Anne. A good example of the Eastlake influence can be found at the J.W. McNutt House, located at 614 24th Street. The home is highly decorated with various shapes of wood shingles covering the house, ornate lathe-turned columns, spindles in porch friezes, and carved panels. The Queen Anne style is common in the district. Notable examples include the Samuel T. Whitaker home at 874 23rd Street and the Andrew J. Warner home at 726 25th Street. Mr. Whitaker was an architect who came to Ogden in 1890, and soon after had this large two-story wood shiplap home with a round turret constructed. Mr. Warner was a realtor who came to Ogden during the boom era and had this classic Queen Anne style home built. It has a sandstone foundation, stain-glassed windows, decorative veranda, onion dome turret, and decorative wall and shingle patterns. Other Victorian styles found in the district include the Richardsonian Romanesque style such as the Madison School at 2418 Madison Avenue; Victorian Gothic style house at 2332 Adams Avenue; and the Shingle style at the Wright home at 566 24th Street.

By far the most popular style during the era was the Victorian Eclectic, a catchall category for buildings that exhibit features from various Victorian styles as well as Classical and even Picturesque styles. During the late 1880s and 1890s the Victorian Eclectic home became popular in all urban settings in Utah, and builders in the Central Bench welcomed the style as it allowed builders and architects great freedom in selecting decorative motifs to achieve a high degree of picturesque intricacy and enhancement of the irregular massing of their design. As numerous Victorian styles were popular, so were various house plans and types. The central block with projecting bays was a particular favorite in the neighborhood, as was the side-passage/entry hall, and also the cross-wing form. As the homes are a beautiful remnant of that era today, the homes were highly regarded during that era as well. As one gentleman who was publishing the city directory of 1890 remarked, “I have never seen a city in which so many men with small incomes own their own houses and have them neatly furnished,” and went on to talk about the magnificence of the residential neighborhood Ogden had established.

The Neighborhood Reaffirmed: 1900-1920

Social History

Rebirth of the City and District

Although times were tough for residents living in the Central Bench during the mid-1890s, by the turn-of-the- century the neighborhood started to regain vitality. Business had been steadily improving during the late-1890s, albeit times would not be as they were during the era that made Ogden a “modern” city (1888-1892). Ogden had reaffirmed itself as the railroading, manufacturing and industrial center of the Intermountain West, and construction of new structures was on the rise. Many looked to Ogden as the place to live in 1900. Turn-of- the-century Ogden was becoming the center for sheep and cattlemen who had been prosperous throughout the United States, to build their homes. The railroad, with its distribution possibilities, made it possible to bring them here permanently. For example in 1902 one of the successful sheep raisers, P.M. Mattson, sought to create a subdivision and have several cottages constructed within the Central Bench District. The land to be platted was to lie between 28th and 29th Streets and Jefferson and Madison Avenues. Although the plans never actualized, serious talk of platting land was being discussed for the first time since the boom days of 1890.

Another factor drawing residents to the city was the fact that homes had deflated in price over the past decade, giving prospective buyers the opportunity to buy a nice home without the sacrifice over former prices. Even though people were continuing to move into the affordable homes over a short amount of time in Ogden, there were not enough homes to house them, either for rent or for purchase. Demand had been steady over the years just preceding 1900, and as many of the construction businesses failed during the depression in the mid-1890s, the supply could not be met. However, after 1900, the tide started to change and many residences started to be constructed and real estate prices subsequently elevated.

Neighborhood Demographics

By 1920 the district started to become a good representation of the city as a whole, and could start to be seen as what Clix Swaner, a long-time Ogden citizen, considers the area, “A history of the families of Ogden.” By now the community had a broad make-up, people of all classes lived in the district. The elite of Ogden had established themselves in the magnificent homes of the Eccles Subdivision and surrounding area; the middle- class found a large number of attractive homes and oftentimes moved into the homes of the people who moved to the Eccles subdivision used to live in, such as those on Jefferson Avenue; and the lower class and working people started to fill in the rest of the neighborhood opting to live in the now more affordable, yet well-built bungalows that had begun to be built. Many Ogden pioneers and early-comers still lived in the district in their original homes, dating back to as early as the 1860s; however, the old homes were soon demolished to make way for the new homes of 1920s. People of non-European descent, however, rarely resided in the district until the early 1900s. During the early years of the district, the line that separated the Central Bench District from the commercial and industrial sector of town also divided people by race.

People of color almost always lived within a matter of blocks near the Union Station, with only two non-white individuals living in the district in 1900. According to the 1900 Census the make-up of the district was as follows: approximately one-third of the district’s homeowners were born in Utah; one-third were born outside of Utah, but from another state in America; and one-third were born outside of the United States, generally from European countries. However, by the 1910s this started to change as more and more Japanese, Chinese, Mexicans, and others moved to the city in larger numbers because of the railroad, and soon started to spread out into the bench area. A case in point is that of a Japanese Hospital that was located in the district, on the corner of 22nd Street and Quincy Avenue. Physician Silgaji Suzuki had immigrated to the United States in 1904, and by 1915 had made his way to Ogden, along with his family, and opened up the hospital at 2204 Quincy. In addition to running the hospital, the Suzukis lived in the home with three other Japanese men until 1925, when they apparently moved out of the city. Prior to this, almost Japanese people had lived on 25th Street near Kiesel Avenue, remembered by many as “J-town.” There they had shops and restaurants catering to Ogden’s Japanese community. The Japanese hospital/house at 2204 Quincy was replaced by a duplex, c. 1945.

The role of women and the impact they had within the district cannot be overlooked. One of the better-kept homes in the district was the one-time home of two of Ogden’s leading businesswomen, Maude and Mary Wykes. The home is a two-and-a-half-story rectangular block shaped wood Victorian era building, located at 1068 23rd Street. The Wykes sisters were natives of Salt Lake City. Their parents had migrated to Utah, from New York City with a Mormon party during the 1860s, although they were not LDS. The Wykes then moved to Ogden in the early 1900s and opened up the M.M. Wykes Company, specializing in ladies furnishings. They stayed in operation until retiring in 1939. In addition to running the store, they were also involved with organizations such as the Women of the Woodcraft and Women’s Relief Corps. The sisters were members of the Congregational Church, and often times associated themselves with the Japanese Church in Ogden.

By the early-1900s an interesting development started to take place with Dutch immigrants. In the late-1800s the LDS Church had started to send a large number of missionaries to Holland. Consequently, the Dutch that had converted to the LDS Church more often than not found their way to large population centers in Utah, primarily Ogden. After making their way to Ogden many of the immigrants slowly started to migrate to the area of 21st Street and Gramercy Avenue. By the early-1900s the majority of Dutch families living in Ogden resided in that vicinity. Well over one-dozen families lived within approximately five blocks of one another, likely the largest cluster of LDS Dutch immigrants in the country at the time. Many of the original homes still exist in the area, an important remnant of LDS Dutch history. As time passed on, however, the Dutch started to live largely throughout the entire city and in other places such as Salt Lake City.

Nonetheless, by the end of World War I, the Central Bench in Ogden was unequivocally one of the most attractive residential neighborhoods in the state (more of the same continued after the war and throughout the 1920s as well). A newspaper article in the “Industrial Review” section of a 1917 edition of the Ogden Standard highlighted five of the homes found in the Central Bench District on its front page, proclaiming, “Ogden an Ideal Home City-Many Beautiful Structures.” By time the 1920s arrived, many in Ogden, particularly those living in the district were doing well and having much success. The district, with its numerous and large variety of homes, solidified itself as the place to live in the “Junction City.”

Architecture

The architecture seen during the very early 1900s was reminiscent of the design during the 1890s, particularly the Victorian element. Homes built now were generally more utilitarian. In contrast to the homes built of wood a decade prior, homes in the early 1900s were almost always made of brick. Although many homes were made of brick in the early 1890s, its use became more ubiquitous in the new century. A good example of the architecture in 1900 can be found at the James G. Paine House at 2103 Adams Avenue. It is a one-story brick Victorian cottage using very little decorative detail, and has a basic rectangular floor plan with a small bay on the north side.

Within a few years the outlook in Ogden, and particularly the bench area, looked even brighter in terms of building. In 1904, a time when new businesses and shops opened up in Ogden to cater to the railroad, several realtors gave their views of the upcoming building season. Some of the remarks were as follows, “The building of houses will increase until houses get to be more numerous, the contractors will have more work than they can handle.” “Real estate is increasing in value and I expect to see a prosperous year.” “Prospects for a great year in real estate never looked more promising.” And, “Ogden has a bright future in the view of real estate, I expect to see a very prosperous season.” This sentiment appeared to be true, as new homes in the bench area, for the Central Bench District continued to reign as the residential hot spot in the city, proceeded to be built.

A good pictorial representation of the era can be found in the book entitled Architecture of Ogden, 1906-1907, highlighting the works of Ogden architects Julius A. Smith and Leslie S. Hodgson. By 1906 it was clear a new wave of architectural type and style was on the city’s forefront. The Victorian element of the past, with its irregular floor plans and highly ornamental styles, started to be rejected and was replaced by the bungalow. It was a phenomenon that was occurring throughout the United States; Ogden was no exception. A good majority of the homes featured in the book are within the district’s boundaries. Some of the homes featured include the H.H. Rollapp House at 2520 Madison Avenue, the F.L. Wright House at 574 23rd Street, and the Ira L. Reynolds House at 2533 Adams Avenue, all three of which were built in the large two-story foursquare configuration. Some early Ogden bungalows Could also be seen, with the J.A. Smith House at 2177 Jefferson Avenue and the Mrs. W.H. Harris House at 873 25th Street. Other fascinating new styles of architecture could also be seen in the district, including the large two-story Dutch Colonial Revival influenced cottage located at 675 25th Street. The city and district was clearly on the verge of resurgence in building and a transformation of styles.

Several other notable homes were constructed in the district during the period. The John Browning House (John Browning being a son of famous gun inventor John Moses Browning) at 2720 Adams Avenue was built in 1905. The home is a bungalow with several dormers and has elements of the Victorian Eclectic style that was so popular in Ogden during the 1890s. To prove that the Victorian era in Ogden was not completely over, some Victorian rectangular block cottages were constructed in 1907, including the Jesse H. Brown House at 2215 Madison Avenue, the Mrs. Annie Andrae Burt House at 2053 Adams Avenue, and The Alma D. Chambers House at 887 23rd Street, which was one of several Chambers family homes on the block.

Another important movement in the Central Bench District starting in 1908 was the building of three-story apartment buildings that designed to help provide housing for the many new workers who had moved to the city. Housing was still not as available as many wished, thus rents rose, and finding a home to own was now difficult to do. Many of the workers who moved to Ogden were constantly on the move, never at one place for an extended amount of time. Thus in 1908, starting with the construction of the Avon Apartments located at 961 25th Street, large 3-story apartment buildings started to be built. The individuals involved in contracting for the apartments ranged from grocers and clerks to the city’s most prominent families, including several former or future mayors. Because of the scarcity of house rentals in Ogden prior to 1908, the contractors could speculate with very low risk. To this point, Ogden apartments were one and two-story vernacular buildings with only a small number of units in each. Thus, a concerted effort was made to provide first-rate housing for the major influx of workers who had come to Ogden. Overall twenty-one 3-story apartments were built in the city between 1908 and 1928, with 15 being located in the bench area. Most of the apartments were done in the basic block style, Prairie style, or Spanish Colonial Revival style of architecture, and were done in brick. Rentals in the district were not limited to the era between 1908 and 1928; they had been a phenomenon in the district for years. According to the 1900 census, over half of the homes in the district were rented out instead of owner/occupied. The trend of rentals would continue as the bungalow and period revival era of the district would come to light, as several duplexes and more multi-family residences would be constructed.

By 1909-1910, due to the strength of railroad and industries related to it, Ogden had once again become a “Queen City of the Rockies.” In fact, during the years 1909, 1910, and 1911, a subdivision was platted in each of those years. The most noted being the Eccles Subdivision, in 1909; the other two include the Manhattan and Hoff subdivisions. Due to its significance, the Eccles Avenue District was placed on the National Register in 1976. Leslie S. Hodgson and Eber Piers were the two architects credited with the design of the homes on Eccles Avenue. They also designed several other buildings in the district, including the LDS Church Branch for the Deaf located at 740 21st Street (designed by Hodgson), and the Albert Scowcroft home located at 2350 Adams Avenue (designed by Piers). The district is also known for the significant families who resided on Eccles Avenue, who were prominent in local, state, and national affairs.

As can be seen through the Eccles Subdivision, and the other subdivisions platted in the district during the era, architecture took on a new clear form in Ogden. The bungalow, synonymous with the Central Bench District, became a giant in the area. In addition to the Prairie style bungalow, which was common in the bench area, other early forms of this style took shape. Prior to 1910, small basic bungalows started to replace the Victorian cottage of the era before. The Arts and Crafts-style bungalow made its appearance, although it never had a huge influence in the district. A good example of this can be found at 2255 Madison Avenue, the home of architect Leslie Hodgson. He designed and built the home in 1913 and in 1934, in one of his most offbeat business dealings, traded this home with his business partner Myrl McClenehan. Other distinct forms of bungalows were also built, and by 1910, as the population in the city grew to over 25,000, the district filled in with these homes.

Architects/Builders

Other architects began to make their names in the Central Bench District during the 1910s. Arthur Shreeve is a prime example. He was born in Ogden in 1885, a son of Thomas and Emma Shreeve. His father owned a grocery store for several years in the district at 2546 Madison Avenue, it had an apartment attached where the family resided. Arthur Shreeve was educated in Ogden city schools and attended the Weber Academy, from there he attended the International Correspondence Schools in Pennsylvania, and later studied in San Francisco under J.W. Foresight and then in Chicago at the Armour Institute of Technology. In 1910 he then returned to Ogden and established an office with fellow Armour graduate D. Leo Madsen. Shreeve, along with Madsen, built several homes in the district, including several on the 2500 block of Van Buren Avenue. After Art Shreeve’s marriage to Inez Farr in 1911, they built several homes in sequence in the district, living in each one until they built a new home and sold the old one. This cycle continued until they built a home on the eastern boundary of the district, at 2415 Harrison Boulevard, in the early 1920s.

In the late-1910s, Mr. Shreeve also teamed up with Fred Froerer, president of the Ogden Home Builders Company, in building several homes in the district. Mr. Froerer was a well-known builder and realtor in Ogden for several years. Subsequently, Art Shreeve’s brother Leland later became the accountant for the firm and their sister Myra Shreeve later married Mr. Froerer. During the 1910s, Mr. Shreeve designed several types of bungalows in the district; some examples lie on the north side of the 1100 block of 24th Street. A good representation of a Prairie style home he designed is found at 884 24th Street. After 1920 he began to design several attractive period revival style homes in Ogden, as well as other places throughout the western United States.

The Wheelwright and Ballantyne families are worth noting as being active builders in the district during this era. Mathew Bristow Wheelwright, the family patriarch, made his way to Ogden in 1855. He was active in the coal and kindling wood business for many years in the city. Shortly after moving to the city, Mr. Wheelwright and his family moved to the vicinity of 25th and Quincy Avenue, starting the family’s legacy in the area which still survives today, as the Wheelwright Lumber Company is located on west side of the 2400 block of Quincy Avenue. Mr. Wheelwright had several children and many of them chose to build and live in area of 23rd to 26th Street and Quincy Avenue in the early 1900s. M.B. Wheelwright’s children opened up a small mercantile store in the 1890s, and in the early 1900s organized the Wheelwright Construction Company. In 1912 the Wheelwright Lumber Company was created and several of their children started to build homes in the district. A few examples of the several homes they built in the district include the Thomas B. Wheelwright House at 2532 Quincy Avenue, and the James L. Wheelwright House at 2562 Quincy Avenue, Hyrum B. Wheelwright House at 2425 Jackson-located just one block directly east of the Wheelwright Lumber Company, and the Wilford Wheelwright house at 2431 Jackson Avenue. Some of the homes they built were unique in the fact that they were vernacular throwbacks to the Victorian era in Ogden. For example, the home at 2562 Quincy Avenue, similar to a shotgun type house with Victorian elements, was built in the mid-1910s. The family continued to be instrumental in the building and remodeling of homes in the district throughout the twentieth century. It has also been noted that Joseph F. Wheelwright, eldest son of M.B. Wheelwright, constructed the first brick house (located somewhere on 26th Street) in Ogden, in approximately 1870.

The Ballantyne family is another notable family. Richard and Caroline Ballantyne came to Ogden in the late 1860s and later resided on 24th Street just east of Adams Avenue, where they raised several children. The Ballantyne family then became very involved in various types of building in the district by the turn-of-the- century, at first with public utilities such as bridge building and street grading. They organized a lumber company (previously mentioned), a real estate office, and a plumbing company. By 1910, Thomas H. Ballantyne, as son of Richard and Caroline, became a well-known contractor and worked as one until as death in 1923. A good example of his work sits at 762 27th Street, a bungalow that he built for his sons Leroy and Thomas C. Ballantyne in 1909. At one time a portion of what is now Gramercy Avenue, between Monroe Boulevard and Quincy Avenue, was known as Ballantyne Avenue due to the building and homes owned by the family in the vicinity.

Community Development and Planning

Public Services in the District

Important to the development of the district, especially during this era, was public utilities. By 1914 the water system of Ogden was fully operational in the district. The city exploited the underground waters of Ogden, as opposed to the rivers and streams flowing from the mountains to the east, as artesian wells were used for the first time within in Ogden, within the district. Ogden’s electric light system was inaugurated through the lighting of an electric light tower in the center of the city in the early 1880s. The steel tower was located on the western boundary of the district, on 24th and Adams Avenue. Following that a hydroelectric plant was established near Ogden Canyon. By the early 1900s these facilities were taken over by the Utah Power and Light Company, a major Utah power utility that served Ogden for many years. The telegraph and telephone also played an important role in the early history of utilities in the district, and natural gas would also become a major factor in many homes in the following decade.

Equally important to the developments previously mentioned, is that of the streetcar system. As the district had grown throughout the late 1800s and into the 1900s, transportation to the commercial and industrial sector of town became an important issue. Street railroads started in 1883 with a mule-powered rail line, and by the turn- of-the-century prominent businessmen Thomas Dee and David Eccles created the Ogden Electric Railway Company, which continued to grow and expand over the next couple decades making an impact in the district and influencing development. Rail lines served the Central Bench District until the early-1930s, when they started to be replaced by gasoline buses. The last tracks of the old rail lines were taken out in the early-1940s.

Commercial Development

Due to the growing development in the bench neighborhood, and as people started to live more and more in the eastern part of the district farther away from town, local grocers and meat markets started to rise up in the area to cater the community. Several started to be built in the 1910s, including the Sawyer Bros. Grocery at 1012 22nd Street, c. 1912; Farnsworth Grocery at 2162 Monroe Boulevard, c. 1914; and the Mollerup Grocer at 2669 Jackson Avenue, c. 1915. Some precursors were the Kasius Grocery at 743 23rd Street, c. 1905; and the Poulter Grocery and Dry Goods Store at 2570 Gramercy Avenue, c. 1893. The Kasius Store was built in 1905, a small commercial block constructed in front of Andrew Kasius’s home. Mr. Kasius, a Holland native, moved to Ogden, with his family, during the boom years to run an umbrella market on Washington Boulevard. In the early 1900s he then moved to the Central Bench District, where he then opened up the grocery store. Mr. Kasius is a good example of a common story in Ogden and the Central Bench District. As many newcomers made their way to Ogden they usually stayed in the industrial/commercial sector of town west of the district. As they continued to live in Ogden, they often worked their way up to the more stable and peaceful community that was the bench.

The Poulter Grocery and Dry Goods store was one of the very first markets east of the commercial/industrial sector of town. The matriarch of the family, Elizabeth Poulter, opened it in 1893 in the Poulter family home. The Poulter’s were Mormon pioneers, coming to Ogden in 1855, and settling in the bench neighborhood as early as 1870. They built several homes in the vicinity of 25th Street and Gramercy Avenue, as is the case with the home and grocery at 2570 Gramercy. While George Poulter went to England for a couple years to serve a mission for the LDS Church, Mrs. Poulter opened up the market to create some revenue for her family at home and to help support and pay for her husband’s church mission in England. The store was a mainstay in the district for seventeen years, until several others were built in its vicinity.

Churches

Most of Ogden’s historic churches are found in the Central Bench Historic District, almost all of which were built by the year 1920. Several of the churches were noted in the Ogden Chamber of Commerce’s 1930 Ogden: the Gateway to the Intermountain West. In fact, all five churches featured in the pamphlet were located in the district. Including the magnificent St. Joseph’s Church at northwest the corner of 24th and Adams Avenue; the Presbyterian Church at the southwest corner of 24th and Adams Avenue (now heavily altered); First Baptist Church of Ogden at southwest corner of 25th and Jefferson Avenue; First Church of Christ, Scientist, at 780 24th Street; Methodist Church at 2604 Jefferson Avenue (part of church was originally J. Pingree’s home built in 1908, then the church purchased the property in the 1920s); and several LDS meetinghouses. Another interesting religious facility was the LDS 4th Ward Theater located at 2323 Monroe Boulevard, which was used as an amusement hall until 1900, when it was then sold and converted into a home.

The District’s Fruition: The 1920s

Community Development and Planning

New Growth

By the time the 1920s rolled around Ogden was doing comfortably well in terms of industry and business, and the Central Bench District was witness to more development than it had seen in years. As many enjoyed good times throughout the rest of the United States, those in Ogden were no different. And in terms of house construction in the bench area, the 1920s were very important, as the district started to fill up and fill in with a “bonanza” of bungalows and period revival homes, for which the district is well known. It was the decade that really focused on the district, as it was the time in which the area became a new home to many. It was also the era just before the city expanded every direction surrounding the Central Bench. As the economy was burgeoning because of the impact felt by the railroad and related businesses, the working class in Ogden welcomed the comfortable and affordable appeal of the bungalow. The bungalow found its way into the American mainstream in the early 1900s, and from 1905 to 1925 it became by far the most popular house type in Utah. Ogden was no different, and many builders, architects, contractors, and construction companies began to surface in the city during this era to provide this highly popular housing style, especially in the early 1920s. The Taylor Building Company, and the work they produced, is a perfect example of the building craze that hit the district in the 1920s.

The Taylor Building Company had made its way to Ogden, from Salt Lake City in late 1921 responding to Ogden’s housing needs. By 1921, Ogden realtors and homebuilders had joined together to find ways in which housing could be obtained by those who needed it; to them good affordable housing was essential. Thus came the Taylor Building Company, which was headed by Harold Bowerman Taylor, who had moved to Salt Lake City in the early 1900s from South Dakota. By the spring of 1922 the company had started building several homes in Ogden, targeting the Central Bench District. Throughout the 1920s the company continued to develop numerous undeveloped subdivisions in the district, constructing over a total of one hundred homes within the area. They specialized in bungalows, but also a built a number of period revival homes. The houses were touted as being well built, affordable, modern, convenient, and attractive. Most the homes were complete with oak floors throughout, tile bathroom floors, enamel finishes, modern lighting and bath fixtures, full basements, and furnace heats. Indeed, the homes were well built and received praise from the Ogden City Building Inspectors.

The homes attracted a wide range of people, including Ogden mayors, businessmen, and a wide range of working and middle class families. The company did as much as they could to sell their homes, such as creating the Taylor Sales Company, a financial division that took care of most mortgages for prospective buyers. The company represented a change in the district; homes in the district were previously built generally for individuals in the location of their desire and liking. Now various homes were built in large quantities in hopes that demand would meet the supply. The company was a mainstay in the city until 1930, when, as was the case with many builders, it went out of business as a result of the Great Depression.

Large building companies were not the only ones to take part in the building action of the 1920s. Local citizens that previously had no real estate or building experience became involved, as was the case with Henry Skinner and his son-in-law Albert Erickson. At the time the two were involved in Ogden with entertainment and performing arts, Mr. Skinner was the manager of the popular Colonial Theater at 2465 Washington, and Mr. Erickson was a musician and music teacher. Their building endeavors started in 1923, when they collaborated with the Taylor Building Company and had a home built at 2710 Brinker Avenue. They owned the home and occupied it for a year and then sold it for a profit to Leo Peck. Then in 1926 the two contacted the Taylor Building Company again and had seven homes built in a small subdivision between 22nd and 23rd Streets, just below Harrison Boulevard. The area was called Rue Anne Court, named after Mr. Skinner and Mr. Erickson’s daughters. After selling the homes in Rue Anne Court, the Skinners and Ericksons moved to Hollywood, California.

Several other builders from Ogden took part in developing the district during the 1920s. Wilford Bramwell is a good example. Wilford Bramwell was born in Plain City, just west of Ogden, in 1881, a son of George and Isabelle Bramwell and was the brother of one-time Ogden mayor Kent Bramwell. He attended Ogden schools and graduated from Weber College in 1898. During the early 1900s, before becoming involved in building, Mr. Bramwell had owned and operated Bramwell’s Books and Stationary Company, and as a hobby raised pedigree chickens for exhibition throughout the country. Drawn by the opportunity of the building industry in the 1920s, he became a contractor. One of his earliest and largest undertakings occurred in 1926, when he designed and started construction of the Bramwell Court, located between Monroe Boulevard and Quincy Avenues and 26th and 27th Streets, the land surrounding his family home. Bramwell’s Court was a bungalow court, a type of development that was popular in the United States but rare in Utah.