Tags

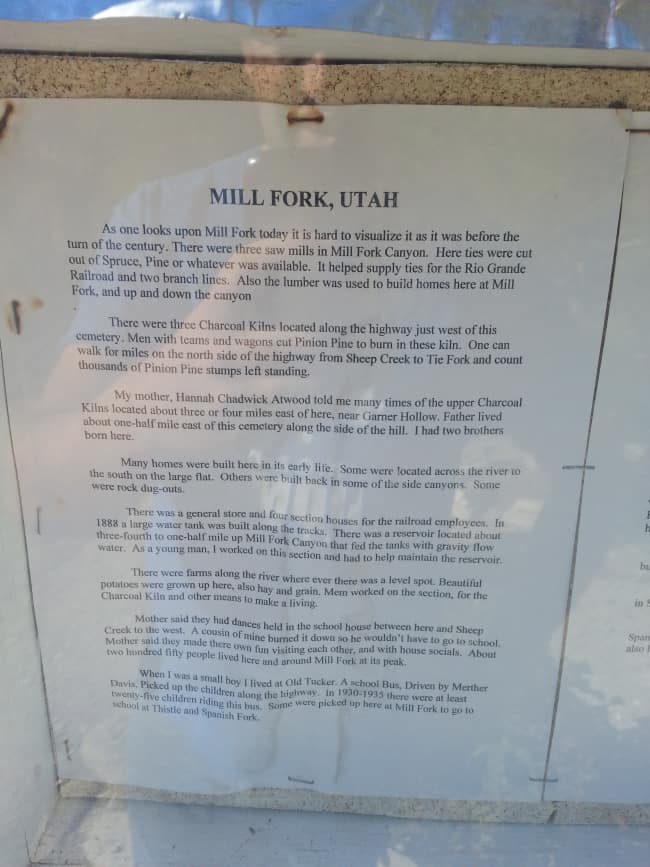

As one looks upon Mill Fork today it is hard to visualize it as it was before the turn of the century. There were three saw mills in Mill Fork Canyon. Here ties were cut out of Spruce, Pine or whatever was available. It helped supply ties for the Rio Grande Railroad and two branch lines. Also the lumber was used to build homes here at Mill Fork and up and down the canyon.

There were three Charcoal Kilns located along the highway just west of this cemetery. Men with teams and wagons cut Pinion Pine to burn in these kiln. One can walk for miles on the north side of the highway from Sheep Creek to Tie Fork and count thousands of Pinion Pine stumps left standing.

Hannah Chadwick Atwood told of many times of the upper Charcoal Kilns located about three or four miles east of here, near Garner Hollow. Her husband lived about a half mile east of the cemetery along the side of the hill and had two sons born there.

Many homes were built here in its early life. Some were located across the river to the south on the large flat. Others were built back in some of the side canyons. Some were rock dug-outs.

There was a general store and four section houses for the railroad employees. In 1888 a large water tank was built along the tracks. There was a reservoir located about three-fourth to one-half mile up Mill Fork Canyon that fed the tank with gravity flow water.

There were farms along the river where ever there was a level spot. Beautiful potatoes were grown up here, also hay and grain. Men worked on the section, for the Charcoal Kiln and other means to make a living.

They had dances held in the school house between here and Sheep Creek to the west. One boy burned it down so he wouldn’t have to go to school. About 250 people lived here at its peak.

The placid outward demeanor of the cemetery belies the fact that nearly half, and possibly more, of its 16 known residents died tragically. The earliest three inhabitants of the cemetery died doleful deaths in June 1893.

Doug and Christie Atwood and others familiar with the Mill Fork Cemetery knew there were unmarked graves in its west section. They did not know until the summer of 2005, however, the names of any of the dead buried there.

The Atwoods recently received a letter from Marcella Martineau Rowe, a resident of Redding, California. Marcella told them three young daughters of Theodore Finch, roundhouse foreman for the D&RGW Railroad at Clear Creek (Tucker) died in mid June 1893 and were transported to the Mill Fork Cemetery for burial. A transcription of an unnamed, undated, historic newspaper article told the following lamentable tale.

The people of Clear Creek considered their children to be reasonably immune from most contagious childhood diseases because of the community’s relatively isolated location in Spanish Fork Canyon. Unfortunately, a young woman from Grand Junction and her child altered Clear Creek’s way of thinking.

The young mother had fled the Colorado city in hopes of making her child safe from an epidemic of scarlet fever that was raging through their community. The two stayed in Clear Creek 10 days. The child played with the children of the small railroad community without warning their parents of the danger to which their young ones were being exposed.

The three Finch children contracted scarlet fever, and their home was quickly placed under quarantine. This prompt action saved the other children in the town, but it could do nothing for the Finch sisters. Four-year-old Georgia Geraldine and three-year-old Effie died on June 14, and their one-year-old sister Edna Vivian succumbed the next day.

General Superintendent Welby of the D&RGW offered a train to transport the three little coffins to the Mill Fork Cemetery free of charge. The newspaper reported that the mourning parents and half of the residents of Clear Creek made the short, somber trip to the graveyard and back.

According to Allen Williams, misfortune struck the Elliott family in May 1905 as Ray Elliott unloaded 100 pound sacks of grain from a wagon on his father’s ranch. His 9-year-old sister Myrtle quietly walked up behind him. Ray, who was hard of hearing, was unaware of her presence.

When he turned from the wagon with a sack of grain in his arms, he tripped over the girl and dropped the heavy bag on top of her. She died from her injuries on May 21 and was buried in the Elliott plot on the lonely knoll.

Myrtle’s father, Edson William Elliott, died a dreadful death in 1908. He and his wife left the ranch at Mill Creek after the children were grown. Edson found a job doing outside carpentry for the Castle Gate Mine, and the Elliotts moved to that community. The new employee temporarily worked as a carpenter inside the mine while he waited for the outside job to open.

Ironically, the former railroad section foreman, who worked for years keeping a stretch of track safe for travel, was struck down and run over on Oct. 6, 1908, by a string of empty coal cars running down the narrow rails inside the mine.

The first car struck Edson and knocked his hat off his head. It flew backward into the open train car. Six more mine cars ran over the hapless man before the eighth car in the train derailed when it struck him. This stopped the string of unloaded conveyances.

Mine workers found Edson’s mangled body, his railroad pocket watch embedded in his cheek. Even though its crystal had not broken, the watch had stopped at the time of its owner’s death.

Price’s newspaper, the Eastern Utah Advocate, simply stated that Edson “was killed while coming out of the mine on an empty trip.” His body, the Advocate said, was taken to Mill Fork for burial.

The poignant tale of Paris and Viola Chadwick Ballard arguably ranks as the most sensational story surfacing from the depths of the old Mill Fork Graveyard. Paris and Viola were raised in Spanish Fork Canyon. The two met, fell in love and married. Years later during the summer of 1919, Paris, who had worked around cattle most of his life, found a job as a range rider for John Dooly on Antelope Island. H.A. Hill, Viola’s first cousin who worked in Salt Lake City for the Oregon Short Line Railroad, found an apartment for the Ballards. On June 28, the childless couple moved into the back half of a cottage owned by Salt Lake City Police Chief J. Parley White.

Viola’s sister, Carrie LaDam, had separated from her husband and needed a place to live. She and her two young children, ages three and five, shared the Ballard’s apartment, which was located on 56 N. 200 West near the Salt Lake Temple.

Mrs. George Dickey and her daughter Marie occupied the front half of the house. Mrs. Dickey considered the Ballards good neighbors, although she did hear them quarreling once.

Mrs. Ballard was sitting on the porch when Marie Dickey, who peered from her window, noticed Mr. Ballard appear at his door. She heard him command his wife to come into the house. When Mrs. Ballard refused to comply, Mr. Ballard walked onto the porch, grabbed her and dragged her inside. The Dickeys could not hear what the Ballards were saying, but they could tell from the angry tone of their voices that they were quarreling.

Carrie LaDam later revealed that jealousy stood at the root of most of the couple’s disagreements. Mistrust festered in Paris’s mind. He felt jealous if Viola even spoke to acquaintances on the street. The fact that Paris’s job on Antelope Island took him away from home for extended lengths of time definitely exacerbated the situation. Carrie claimed Paris even threatened to take his wife’s life on various occasions.

The latest object of Paris’s suspicion and jealousy became H.A. Hill. He ate supper with the sisters almost every night that Paris was absent, and the jealous husband suspected Hill of satisfying more than one type of appetite while at the house.

During the second week of September, the 38-year-old husband returned from Antelope Island and spent several days in the city. The couple argued and Paris threatened to kill his comely wife. Panic stricken, Viola set out for the police station, accompanied by Hill.

Viola explained her situation to the desk sergeant who sent her to the county attorney’s office where she could get a restraining order against her husband. The attorney expounded his opinion that a scare from an officer would frighten her husband from his purpose.

Deputy Sheriff Arthur Waller accompanied Viola home. When they arrived, Paris was not there, and the deputy left. Paris had taken his clothes with him, making it appear as though he had gone back to Antelope Island — he had not.

About ten o’clock that morning, Paris bought a .38 caliber revolver and some ammunition. He also purchased a pint of whisky and downed about half of the liquid courage before returning to his apartment shortly after noon on Friday, Sept. 12. Mrs. Dickey stood in the front yard when Paris walked to the porch, climbed the stairs and entered the house. He found Viola alone. Mrs. Dickey later talked to reporters from the Deseret News and the Salt Lake Tribune. She told them that immediately after the irate husband entered his apartment she heard him threaten his wife by saying, “I’m going to shot you!”

Viola screamed, “Oh, don’t, don’t, for God’s sake, don’t!” Then she made a final appeal to the jealousy-crazed man, “Oh, please forgive me.” Two quick shots followed and Viola screamed. Seconds later, two more shots rang out. Then there was silence.

When officers arrived, they found two bodies in the bedroom. Paris lay on the bed, breathing almost imperceptibly. He had apparently shot himself in the left side of his chest first, and then put a slug through his head. He died in the hospital eight hours later.

Viola lay on the floor between Paris’s feet. The Tribune deduced that her position indicated she had fallen on her knees in front of her husband before receiving a shot to the head and another to the body. She appeared to have died instantly.

This murder/suicide was not justifiable, of course, but was Paris’s jealousy unfounded? Viola’s sister Carrie told the Tribune, “Jealousy alone, and without cause, was solely responsible for the murder.” However, Viola’s last words, “Oh, please forgive me,” and her apparent position of supplication at the time of her death seem to indicate there may have been some justification for Paris’s suspicion.

Doug Atwood recently said the feelings of the two families regarding the question of Viola’s fidelity were divided in 1919, and they remain so today. Regardless of this division of opinion, the families decided to bury Paris and Viola side by side on the secluded hummock in Spanish Fork Canyon.

In 1926, the little cemetery at Mill Fork received its last permanent resident, Aaron Chadwick. Since that time, the sacred ground shrouding so much tragedy has remained a lonely one, but it is certainly not unloved. Due to the dedication of the Atwood, Chadwick and Elliott families, the cemetery, like the people buried within its sheltering fence, has undergone a resurrection.(*)

Pingback: Spanish Fork Canyon Kilns | JacobBarlow.com