Tags

The Mountain Meadows Massacre

In early September 1857, about 140 people camped in this valley. Most of them were families from northwest Arkansas. Led by Captains John T. Baker and Alexander Fancher, they were headed to new opportunities in California. Their worldly possessions included about 35 wagons, several hundred cattle, and many mules, horses and oxen.

Beginning on September 7, the camp was attacked by a group of Mormon militiamen and the Paiute Indians they had recruited. In a five-day siege fueled by complex hostilities, the attackers killed at leave 10 men who fought valiantly to defend family and friends.

The emigrants fought off their attackers until September 11, when Mormon militiamen entered the encampment under a white flag of truce. The militiamen deceived their victims into surrendering weapons and property in exchange for protection and safety.

The militiamen separated the emigrants into three groups and marched them from the camp. The wounded and some small children rode in wagons, followed by women and older girls on foot with other children. Men and older boys walked some distance behind, each escorted by a Mormon militiaman.

At a prearranged signal, militiamen shot the men, older boys, and some of the wounded. Mormons and Paiutes surged from their hiding places and, in a matter of minutes, massacred most of the remaining emigrants, including the courageous women who were attempting to protect the children and flee. The victims’ voices fell silent, except for the sobbing of 17 small surviving children. The dead were stripped of their clothing and left without decent burial. Their wagons, livestock, and other property were plundered.

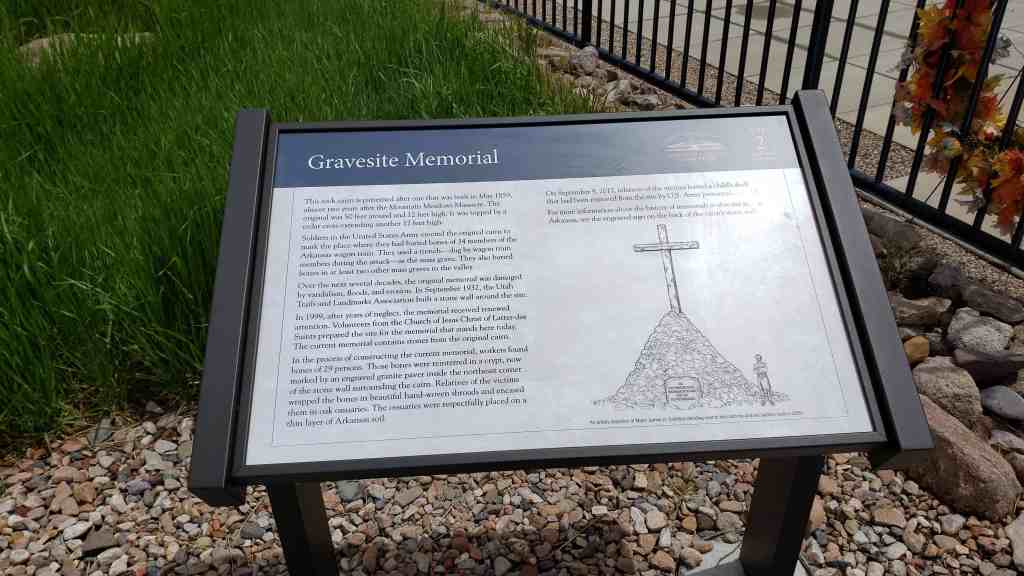

In 1859, soldiers in the United States Army buried the victims’ scattered, scavenged remains.

Seventeen years after the massacre, a federal grand jury indicted nine Mormon militiamen for crimes related to the siege and massacre. About 50 other militiamen were involved, along with an unknown number of Paiutes. Only one, John D. Lee, was brought to trail and convicted. He was executed near the massacre site on March 23, 1877.

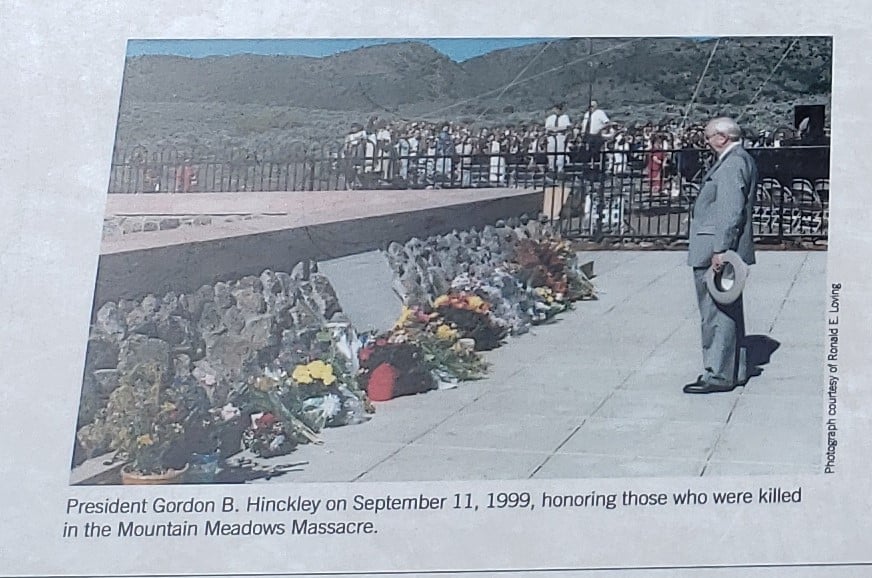

The Mountain Meadows Historic Site was added to the National Register of Historic Places (#75001833) on August 28, 1975.

The Mountain Meadows Massacre Site has 4 memorials:

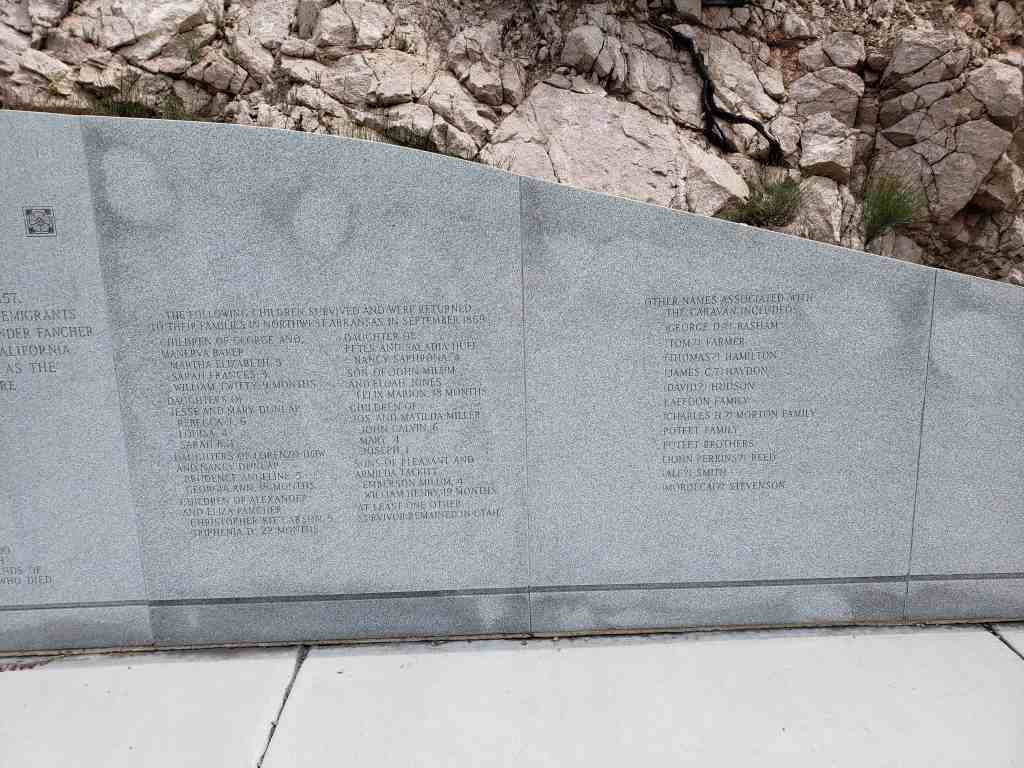

- The Overlook Memorial where a trail leads to a memorial wall at the top of a small hill. Etched in the granite wall are names of victims in the Mountain Meadows Massacre.

- The Gravesite Memorial, where a rock cairn marks the resting place of at least 30 victims in the massacre. Another monument nearby honors some of the emigrants who were killed in the initial siege.

- The Memorial to the Men and Older Boys, a monument honors the men and older boys of the wagon train who were killed in the massacre.

- The Memorial to the Women, Children, and Wounded. A monument honors the women, children and wounded of the wagon train who were killed in the massacre.

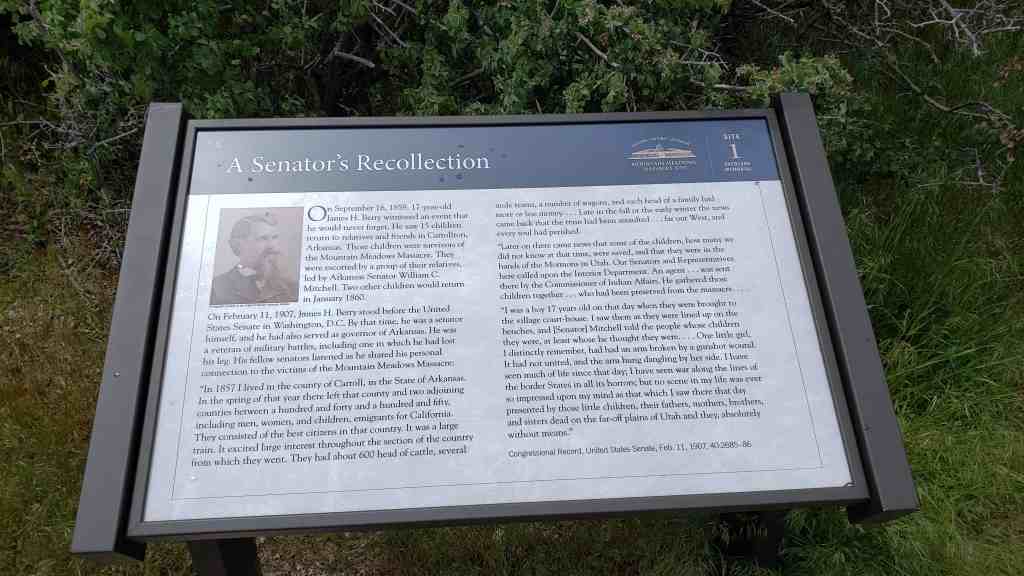

A Senator’s Recollection

On September 16, 1859, 17-year-old James H. Berry witnessed an event that he would never forget. He saw 15 children return to relatives and friends in Carrollton, Arkansas. Those children were survivors of the Mountain Meadows Massacre. They were escorted by a group of their relatives, led by Arkansas Senator William C. Mitchell. Two other children would return in January 1860.

On February 11, 1907, James H. Berry stood before the United States Senate in Washington, D.C. By that time, he was a senator himself, and he had also served as governor of Arkansas. He was a veteran of military battles, including one in which he had lost his leg. His fellow senators listened as he shared his personal connection to the victims of the Mountain Meadows Massacre:

“In 1857 I lived in the county of Carroll, in the State of Arkansas. In the spring of that year there left that county and two adjoining counties between a hundred and forty and a hundred and fifty, including men, women, and children, emigrants for California. They consisted of the best citizens in that country. It was a large train. It excited large interest throughout the section of the country from which they went. They had about 600 head of cattle, several mule teams, a number of wagons, and each head of a family had more or less money…. Late in the fall or the early winter the news came back that the train had been assaulted… far out West, and every soul had perished.

“Later on there came news that some of the children, how many we did not know at the time, were saved, and that they were in the hands of the Mormons in Utah. Our Senators and Representatives here called upon the Interior Department. An agent… was sent there by the Commissioner of Indian Affairs. He gathered those children together… who had been preserved from the massacre….

“I was a boy 17 years old on that day when they were brought to the village court-house. I saw them as they were lined up on the benches, and [Senator] Mitchell told the people whose children they were, at least whose he thought they were…. One little girl, I distinctly remember, had had an arm broken by a gunshot wound. It had not united and the arm hung dangling by her side. I have seen much of life since that day; I have seen war along the lines of the border States in all its horrors; but no scene in my life was ever so impressed upon my mind as that which I saw there that day presented by those little children, their fathers, mothers, brothers and sisters dead on the far-off plains of Utah and they, absolutely without means.”

The Surviving Children

In 1859, Major James H. Carleton interviewed Mrs. Rachel Hamblin, who lived a few miles north of the massacre field. Major Carleton carefully recorded her account of the surviving children, who were brought to her home on September 11, 1857, after witnessing the murder of their parents:

“At length between sundown and dark of the last day, I heard a firing greater than before, and more distinct. This is the time when the last of them were killed…. In about an hour, a wagon drove up to our house containing seventeen children in it, the most of them crying; one, a girl about a year old [Sarah E. Dunlap], had been shot through the arm; and another girl, about four years old [Sarah Frances Baker], had been wounded in the ear; their clothes were bloody…. The little girl who was shot through the arm could not well be moved. She had two sisters, Rebecca and Louisa, one seven and the other five [records show they were ages six and four], who seemed to be greatly attached to her. I persuaded [John D.] Lee not to separate them, but to let me have all three of them. This he finally agreed to, and the children stayed with me, and I nursed the wounded child…, though [she] has lost forever the use of [her] arm. The next day…, Lee and the rest started up the road with all the rest of the children in a wagon; and the Indians scattered off.”

Leaders of the Arkansas Wagon Train

Accounts of the Arkansas wagon train list two leaders: John T. Baker (1805-1857) and Alexander Fancher (1812-1857).

John T. Baker was a farmer and cattleman, described as a shrewd trader, a warm friend, and a bitter enemy. He and his family lived along Crooked Creek, near the southern border of present-day Harrison, Arkansas.

In 1857, Baker led a group of relatives, acquaintances, and others in a wagon caravan headed to California, where he and his son John H. Baker had previously spent some time. He took 138 head of “fine stock cattle,” nine yoke of oxen, two mules, one mare, one large ox wagon, guns, saddles, bridles, camp equipment, and provisions for himself and five workhands. Three of his adult children went with him. His wife, Mary, and the other children remained in Arkansas, planning to go west later.

Before Baker left Arkansas, he wrote his will. He acknowledged that he knew “the uncertainty of life and the certainty of death” but not the time of his “dissolution.” He said, “First, I will at my death my body a decent burial in the bosom of its mother Earth and my spirit to the God who gave it.”

Alexander Fancher was a farmer and cattleman and a veteran of the Black Hawk War in Illinois. In the 1840s he and his wife, Eliza, moved with their children to Carroll County, Arkansas, and so did his brother John and his family. In 1850 the two brothers and their families moved to southern California. Soon after that, Alexander and his family returned to Arkansas. He obtained a land patent on Piney Creek in Carroll County in 1854 and settled in southern Benton County, where he acquired more land and became a justice of the peace.

Tradition suggests that Alexander, like John T. Baker, recruited family members, neighbors, and perhaps others to go to California in 1857. He and Eliza and their nine children set out on the adventure together. They took six toke of oxen, eight mules, three horses, four wagons, and as many as 200 head of cattle.

All these emigrants crossed the plains and went through the Rocky Mountains. They journeyed together from the Salt Lake City area, southward through Utah Territory.

In September 1857, the massacre at Mountain Meadow cur their journey tragically short and denied John T. Baker’s request for a decent burial. Baker was brutally murdered, along with his three children who were with him, one grandchild, a son-in-law, and a daughter-in-law. Alexander and Eliza Fancher were also murdered, as were seven of their children. Three Baker grandchildren and two Fancher children survived. Two years later, they and twelve other surviving children were returned to the care of relatives in Arkansas.

Mountain Meadows Massacre Site has been designated a National Historic Landmark. This site possesses National significance in commemorating the history of the United States of America.

Execution at the Scene of the Crimes

In September 1874, a federal grand jury indicted nine Mormon militiamen for crimes related to the siege and massacre. Some of those men immediately went into hiding as fugitives from justice. About 50 other militiamen were involved in the massacre, along with an unknown number of Paiute Indians. Only one, John D. Lee, was brought to trail and convicted.

On March 23, 1877, almost 20 years after the massacre, federal officials took Lee to the scene of the crimes. Not far from this very spot, he was executed by firing squad. He was buried about 120 miles from here.

Pingback: Fort Harmony | JacobBarlow.com

It appears lots of flowery rhetoric was liberally used in this write up. It would interesting to know what “really” happened and why some religious Mormons all the sudden turned into bloodthirsty murderers.

Yeah, sadly, as with all history we can only go by what was recorded and documented and there’s no way to know if that was the truth or not but we go with it because it’s better than nothing.