Hurricane Canal

The following History and Statement of Significance for the Hurricane Canal was prepared by Allan Comp, Project Historian for the Historic American Engineering Record work in Utah in 1971-1972.

The construction of the Hurricane Canal is one of early Utah’s proudest stories of pioneer determination. Built completely by hand, the 7.5 mile canal clings to the sheer walls of the Virgin River Canyon before leaving to follow the Hurricane Fault and then encircle the flat farmlands of the Hurricane Bench. The canal took eleven years and $60,000 to build, most of the capital being represented by the labor of men who paid for their shares in the canal company by working on the canal during the winter months. The completed canal brought water to 2000 acres of parched bench land and created the now successful village of Hurricane, Utah.

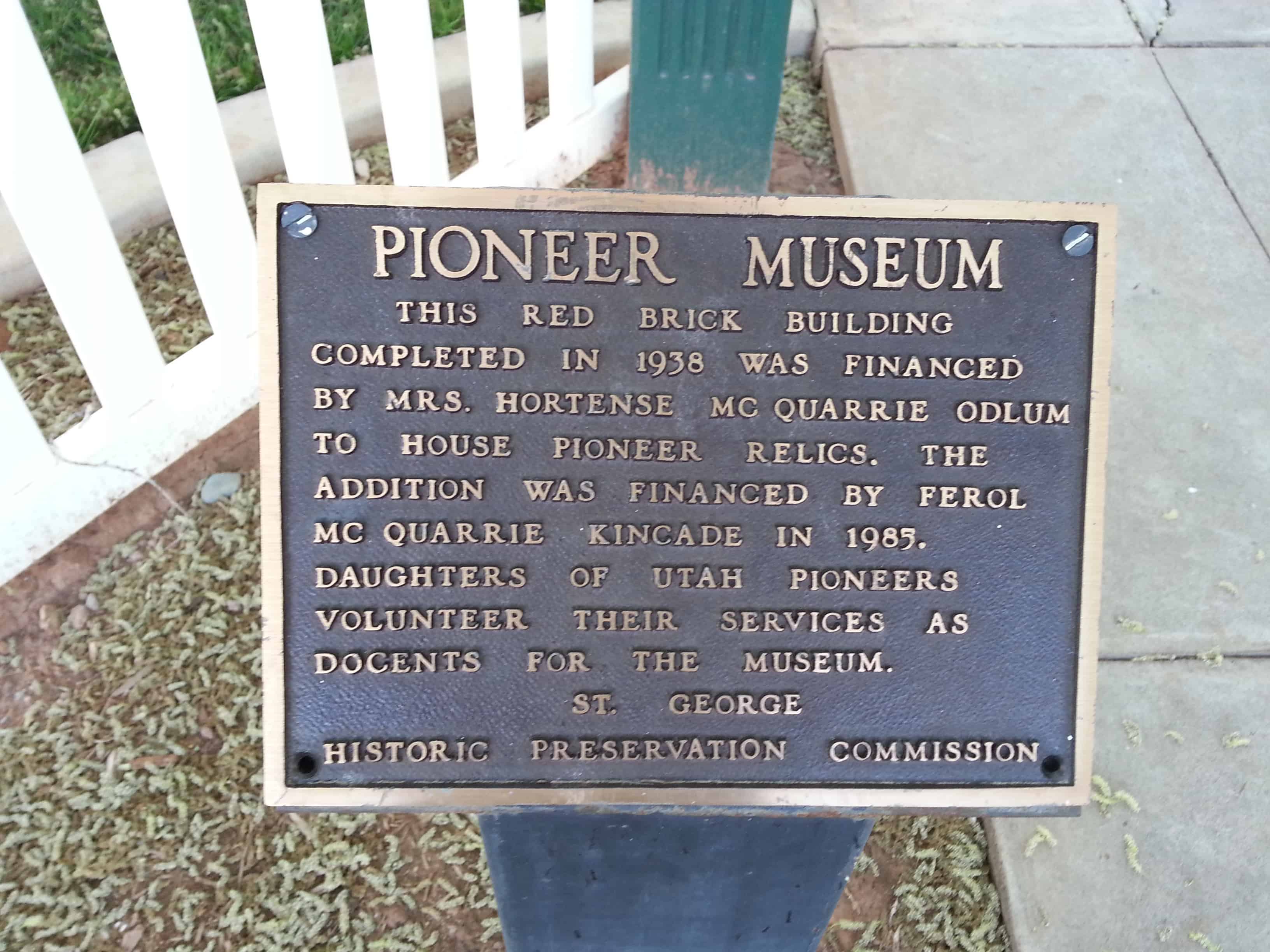

The Hurricane Canal in Hurricane, Utah was added to the National Register of Historic Places (#77001324) on August 29, 1977. The text on this page other than this paragraph and the list of post links below is from the nomination form for the historic register.

Related Posts:

ORGANIZATION

Early residents of the area settled on the small bottom lands of the upper Virgin River Valley and elsewhere, but the erratic floods of the river diminished the available land while expanding families increased the need for more farmland. As some families began to move out of the area in search of new lands, others turned their eyes to the Hurricane Bench. If farms could be established here families could remain together and lands would be freed from the threat of flood. But water was essential to this expansion, and few thought a canal was possible. In the 1860’s, Erastus Snow and pioneer surveyor John M. MacFarlane explored the area and decided a canal was not a feasible undertaking. Brigham Young’s son John came to the valley in 1874 with the idea of a canal to take water out on the bench, but after a quick survey decided it was impracticable and went home. The little towns of Virgin, Mountain Dell, Duncan’s Retreat, Rockville, Grafton, Springdale, and Toquerville, prodded by their need for new land, continued to wish for some way of getting water to the bench despite the seeming impossibility of the task.

Finally, two men from the area, James Jepson and John Steele, decided in 1893 that a dam and canal could be built and began to interest others in the project. By the end of June a committee of six had been formed and, after investigating the canyon, returned a favorable report. The Hurricane Canal Company was soon created and the first meeting held in Toquerville Hall on July 11, 1893. August 25 brought another stockholders meeting, this time to hear the preliminary report of County Surveyor Isaac MacFarlane. He reported that the canal could be constructed, that it would have to be about 7.5 miles in length, would require a dam fifteen feet high, and would irrigate about 2000 acres. Although MacFarlane did not estimate costs, his report was accepted. The meeting then moved that the company incorporate the begin construction. J. T. Willis was appointed superintendent of construction on November 15, 1891.

CONSTRUCTION

Every reporter and historian who has visited the canyon of the Virgin River and the canal site comments on the impossibility of appreciating the difficulty of the undertaking. The steep canyon walls are chiefly lime rock and conglomerate which would often slide down the sides of the canyon after excavation was begun, burying the canal route under additional tons of cover. In other places fills had to be made with loose rock or a flume on trestle-work built across the opening or gap. There was no road into the canyon during the first year so all materials for canal and dam construction, as well as tools, bedding and food had to be carried in by hand.

Most of the work was done between November and May when farm chores were less demanding. Workers camped at the construction site and transients were often put to work for their board. Construction tools were quite simple. Except for a short distance near the dam, it was not possible to use horse teams with plows and scrapers so most of the work had to be done by hand. Wheelbarrows, picks, shovels, crowbars, and hand-driven drills were the basic tools used in the construction of the 12-foot grade or bed for the canal which was 8 feet wide and 4 feet deep.

Canal company shareholders built the canal by the contract or piecework method. The working survey marked off the route in 4-rod lengths, then carefully estimated the cost of construction for each length. These lengths or stations were taken up by stockholders working out their stock payments at $2.00 per day. The survey estimates allowed 15 cents per cubic yard for earth excavation, 75 cents per loose rock and gravel, and $1.25 for solid rock. When workers could demonstrate that the estimates were incorrect, adjustments were made.

Building the dam turned out to be much more difficult than originally anticipated. Specifications called for a structure seventy-five feet in thickness up and down the river, and five feet higher than the bottom of the canal. The river is about forty feet wide at the place called the Narrows where the dam was built. The sides and bottom of the river are solid rock, the north side was a solid limestone cliff over 100 feet high and on the south was a rock that rose nine feet to a shelf above the river. The site was ideal for a dam, but inexperience with construction and the raging floods of the Virgin led to several disappointments.

The plan was to use the shelf on the south side for a spillway and during the winter of 1893-1894 huge rocks were blasted from the sides of the canyon and dropped into place as an anchor. Smaller rocks were then used to fill in and complete the dam. The finished structure looked sturdy enough and the canal company paid the Isom Company $1150.00 for its work. About a year later flood water came surging out of the Narrows, picked up the dam and left the huge boulders strung along the river below the dam site.

For its second attempt the company secured a big pine log from the Kolob Mountains north of Virgin and laid it across the river by setting one end into a hole in the limestone cliff and the other into a slot cut into the south shelf. Juniper posts were then laid with their butts on the log and their tops upstream in the river and the whole mass weighted down with rocks. This dam held for about a year until another flood lifted the log and its load of juniper posts and rock out of its mountings and carried the timber downstream. The third time proved the charm. The pine log was recovered and put back in its slots and junipers again placed with their tops upstream. This time two layers of rocks were placed on the juniper logs and then the whole mass was woven together with heavy galvanized wire. The dam held. It had taken about six years and three attempts, but there was now water available for the canal to carry.

anal to carry. If the dam was difficult, the canal was only more so. Carving a twelve foot bed out of solid limestone or loose conglomerate was hard and dangerous work. Time dragged on and work progressed slowly. Landslides wiped out months and even years of work, tunnels had to be blasted through solid rock, flumes on trestlework were built to span open spaces like Chinatown Wash. Winter after winter passed and still the canal remained uncompleted. Discouragement began to overtake the workers until by 1901 only seven or eight men were still working on the canal. As progress came to a standstill, the canal board realized it must find the cash necessary to supply construction needs or work would stop altogether.

Stockholders had considered asking the L.D.S. Church for help as early as 1898, but four more years of effort passed before the canal company decided the assistance was essential. Finally, in 1902 James Jepson, one of the originators of the canal, went to Salt Lake City for an audience with Church President Joseph F. Smith. After a brief but determined exchange between Jepson and Smith, Jepson returned home with the $5,000 cash the canal company needed.

The stimulus of Mormon Church support and the $5,000 cash were sufficient to renew the spirit and the treasury of the company and work again went ahead. On August 6, 1904, eleven years after the canal was begun, water flowed over the dam spillway, through the canal and onto the Hurricane Bench.

SETTLEMENT

When the company formed in 1893 each share of stock entitled the owner to one acre of farm land with primary water right and an equity in a town lot. Both fields and town lots were distributed by drawing, a sort of pioneer land lottery. Individuals were restricted to a twenty acre maximum because the company wanted to keep the size of stockholdings down to a size men could afford to carry (numerous assessments were levied on the stock to help defray canal construction expenses) and also to make it possible for all men, young and old, to get farms and homes rather than just a few wealthier men owning all. The only exception to the twenty acre maximum was made for men with grown sons who were each allowed twenty acres.

With water on the bench, the 11-year-old company stock could finally deliver what it had long promised and farming on the new lands began almost immediately. Some grain was raised in 1905 (some fields producing fifty bushels of wheat per acre) and in 1906 Mr. and Mrs. Thomas P. Hinton moved into a wooden granary to become the first residents of Hurricane. Other stockholders farmed their lands by camping during the week and then returning home for the weekend. Ten families established homes in Hurricane in 1906 and although there was still trouble with the new ditch breaking, a rather common event until the structure settled, the new lands of the Hurricane Bench proved themselves well worth the struggle to bring in irrigation water.

CONCLUSION

If the Hurricane Canal is considered within the secular framework of technological history, a somewhat analytical perspective becomes possible. As an engineering accomplishment, the Hurricane Canal can hardly be compared favorably with earlier canals, be they Egyptian, Roman, Medieval, or even early American. The Hurricane Canal is perhaps best seen as the recognition of necessity. New lands and the water to irrigate them were essential if families were to stay intact. To bring water to those lands a canal had to be constructed, Once that necessity was recognized, the rest followed as a matter of course. While one may marvel at men willing to accomplish their goals by using rather primitive hand tools in the midst of a rapidly industrializing society, it is their determination and not their engineering prowess which should be most admired.

DESCRIPTION

The Hurricane Canal begins at a diversion dam constructed on the Virgin River at a place known as the Narrows. The dam is a combination of existing river boulders and infill boulders that were placed without mortar. The dam was washed out twice before successfully withstanding floods and high waters. Later concrete was poured to help stabilize the dam.

The canal follows along the south side of the Virgin River in a westerly direction running along the face of the Virgin River Canyon walls for a distance of approximately three and one-half miles. It then leaves the canyon and turns south along the west slope of the Hurricane cliffs for a distance of approximately three miles where it leaves the cliffs turning west to provide water for the fields located on the Hurricane Bench.

The pioneers blasted a total of twelve tunnels and constructed six wooden flumes, most of which have been replaced by metal flumes. The canal is laid out on a twelve foot wide shelf of conglomerate and lime rock, and in one place gypsum. The inside dimensions of the canal are eight feet wide and four feet deep. Frequent floods and landslides have washed out portions of the canal, but it is kept in good repair. A rider makes regular trips along the canal to inspect for breaks and carry out maintenance work.

As the canal flowed past the town along the Hurricane cliffs it provided water for part of the community as ten cisterns were located along the canal to collect and hold water. With the completion of a more modern water system, the ten cisterns were abandoned.

The canal still follows the same course as when first completed in 1904. Located high above the Virgin River the canal can be followed on foot only with difficulty and the exercise of extreme caution. The narrow trail and sheer drops to the canyon bottom limits access to the canal.