Tags

Avenues, Historic Buildings, Historic Districts, Historic Homes, Historic Markers, NRHP, Salt Lake City, Salt Lake County, utah

Avenues Historic District

The Avenues in Salt Lake City are full of historic buildings and homes. I had pages created for Historic Homes in Salt Lake and Historic Buildings in Salt Lake but there were enough in the Avenues I wanted to separate them out.

The Avenues Historic District was added to the National Historic Register (#80003915) on August 27, 1980.

Slowly trying to document every property in The Avenues, choose a page below to see properties along that street or avenue:

| First Avenue | A Street |

| Second Avenue | B Street |

| Third Avenue | C Street |

| Fourth Avenue | D Street |

| Fifth Avenue | E Street |

| Sixth Avenue | F Street |

| Seventh Avenue | G Street |

| Eighth Avenue | H Street |

| Ninth Avenue | I Street |

| Tenth Avenue | J Street |

| Eleventh Avenue | K Street |

| Twelfth Avenue | L Street |

| Thirteenth Avenue | M Street |

| Fourteenth Avenue | N Street |

| Fifteenth Avenue | O Street |

| Sixteenth Avenue | P Street |

| Seventeenth Avenue | Q Street |

| Eighteenth Avenue | R Street |

| S Street | |

| T Street | |

| U Street | |

| Virginia Street |

From the National Register’s nomination form (1980):

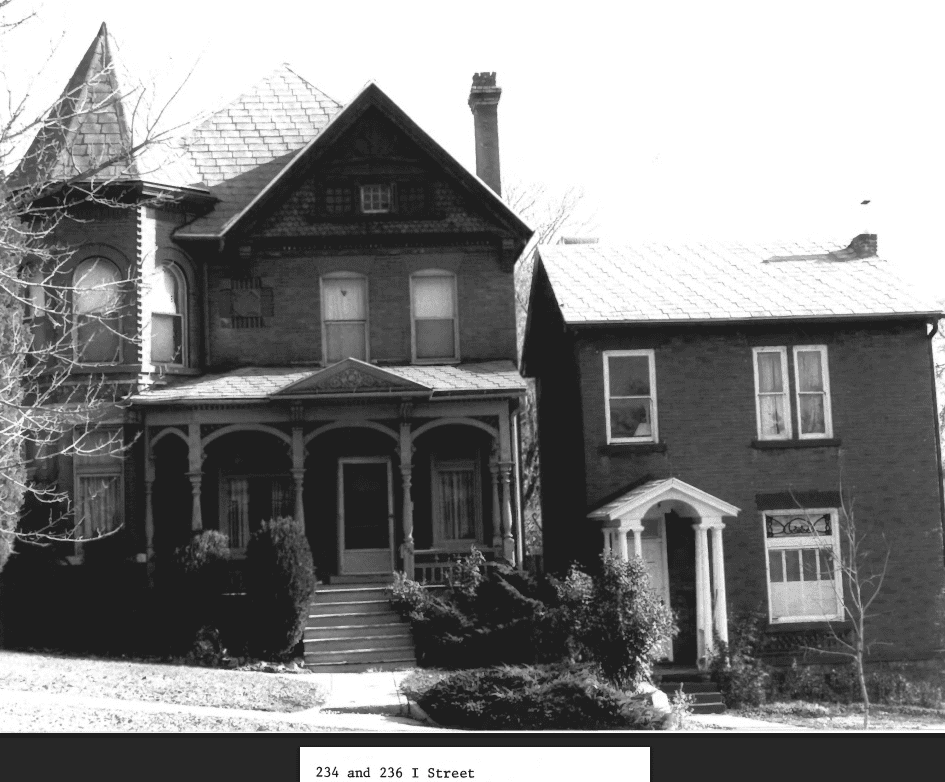

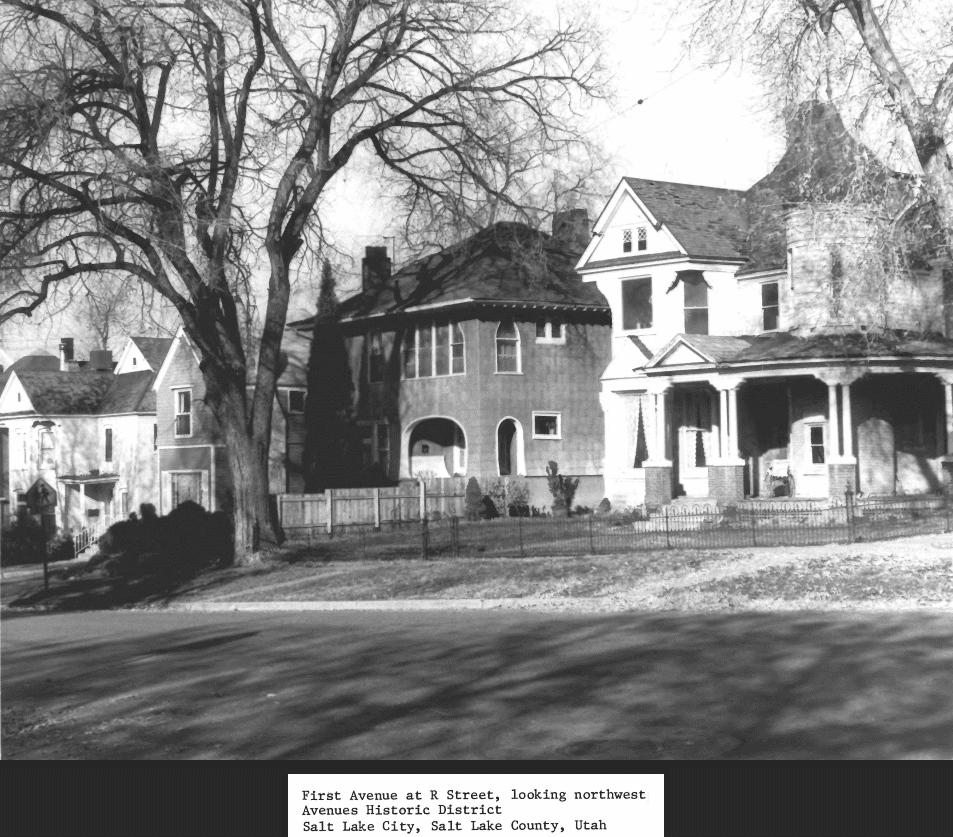

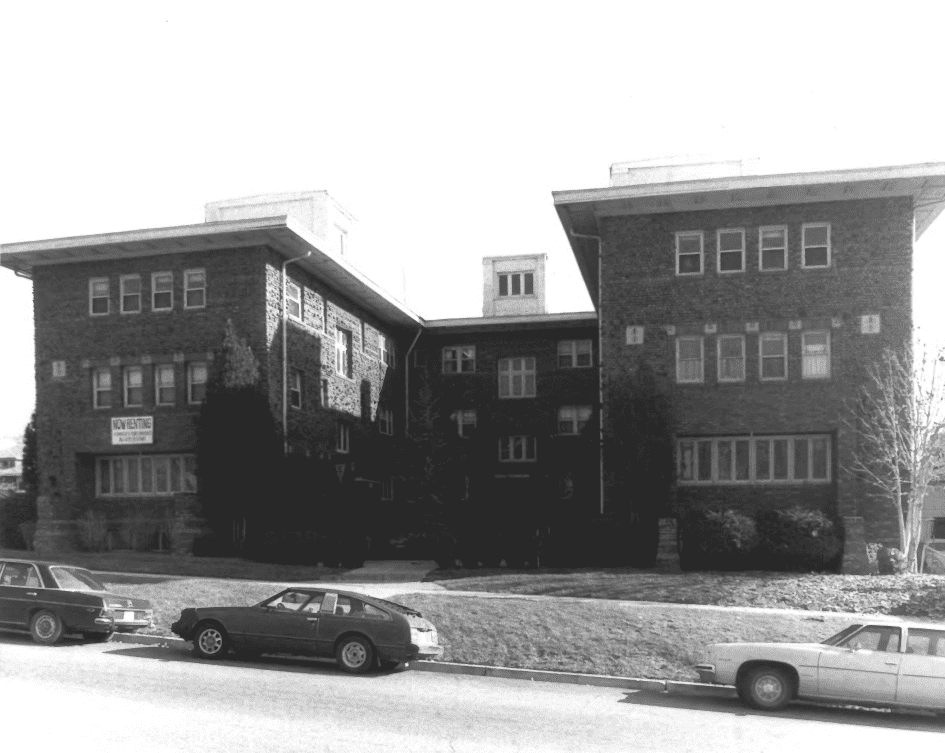

The Avenues is a large historic district of almost 100 square blocks of late 19th and early 20th century domestic architecture. Most of the structures are 1 1/2 to 2 1/2 stories. Beginning around the turn of the century a number of apartment buildings in various revival styles were built in the southwest corner of the district.

Over one hundred architect-designed homes have been identified in the district, in styles from Queen Anne to the Prairie Style. These structures are a significant element of the visual character of the district, which is unusual in its integration of architectural styles. The diversity of styles is a result of the subdivision of the original blocks, originally laid out with four lots to the block. As the neighborhood changed, more and more of the original lots were subdivided by the original owners, producing a diversity which is one of the important characteristics of the district. Several significant public and commercial buildings remain in the district, including Rowland Hall-St. Marks School (National Register), the Danish Evangelical Lutheran Church, and the Twentieth and Twenty-seventh LDS Wards.

There are a total of about 2,238 sites within the district. One hundred forty-three of these are significant and categorized as follows: 48 significant for both architecture and history; 57 significant for architecture, and 29 for history.

There are 116 intrusions which make up less than six per cent of the buildings in the district, and are primarily recently constructed apartment buildings, with a few large, new commercial structures. Brigham Young’s Grave, 140 First Ave, has been included in the district as a significant site, both because of Brigham Young’s importance as a Mormon and political leader and pioneer, as well as the general feeling of the grave as an integral part of the Avenues. In addition, this is the only “family plot” cemetery in the Avenues, and this portion of the area was owned by Young, close to his residence on South Temple.

The Avenues neighborhood of Salt Lake City is the northern-most section of the crescent formed by the Wasatch Mountains on the eastern boundary of the Salt Lake Valley. Unlike the long eastern section of the crescent which flattens out partway up the slope to form the “East Bench,” the Avenues is relatively steep all the way to the crest of the foothills. The difficulty of getting water to this slope delayed the settlement of the greater part of the area until almost the end of the nineteenth century.

The Avenues, laid out in the early 1850’s as Plat D of Salt Lake City, was the first section of the city to deviate from the original city plan of ten acre blocks. Probably a consequence of the steep slopes and the lack of water on the “Dry Bench,” the smaller streets and blocks of the Avenues resulted in a streetscape considerably different from the rest of the city. The differences became even more pronounced when the quarter-block lots were subdivided by their original owners, sometimes with houses so close together that blocks assumed almost the appearance of row houses.

The variation from the original city plat is also reflected in the street names. Originally the north-south streets were named for trees, and the four east-west avenues were named Fruit, Garden, Bluff and Wall Streets. By 1885, the east-west streets had become First, Second, Third and Fourth Streets; and the north-south streets had been lettered, from A to U Streets (V Street became Virginia).

The few remaining maps make it difficult to determine the pattern of house and street development in the Avenues. The history of Darlington Place, in the area of about First to Third Avenues between P and S Streets, is one documented example. Beginning in about 1890, Elmer Darling and Frank McGurrin began selling lots and building homes. By 1892, Darling reported in the New Year’s Day issue of the Tribune that “fifty residences adorn our Darlington Place which were not there in 1890.” Recognizing the developers’ success, streetcar companies extended lines on First and Third Avenues through the new development.

Improved transit, along with the expanded water supply on the Avenues after 1900, accelerated the construction of homes on streets that had been platted (but not settled) since the mid-1880’s. As a result, architectural styles tend to reflect the pattern of development. Most of the two and a half story Victorian era homes are found below Fourth Avenue; above Seventh Avenue the majority of homes are one and a half story bungalows of various stylistic variations.

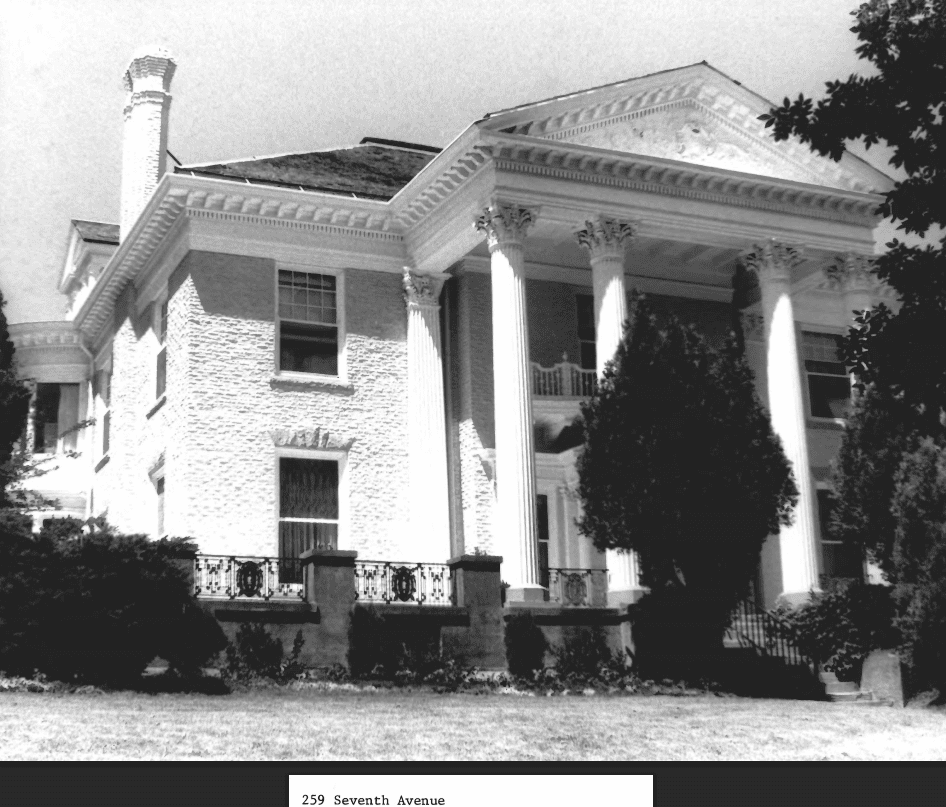

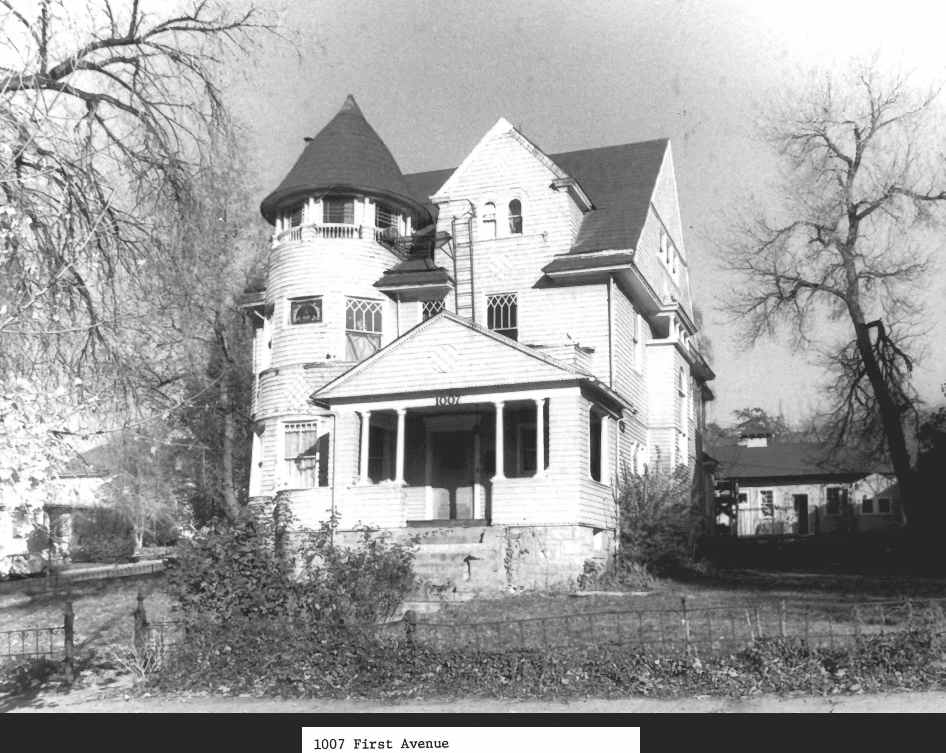

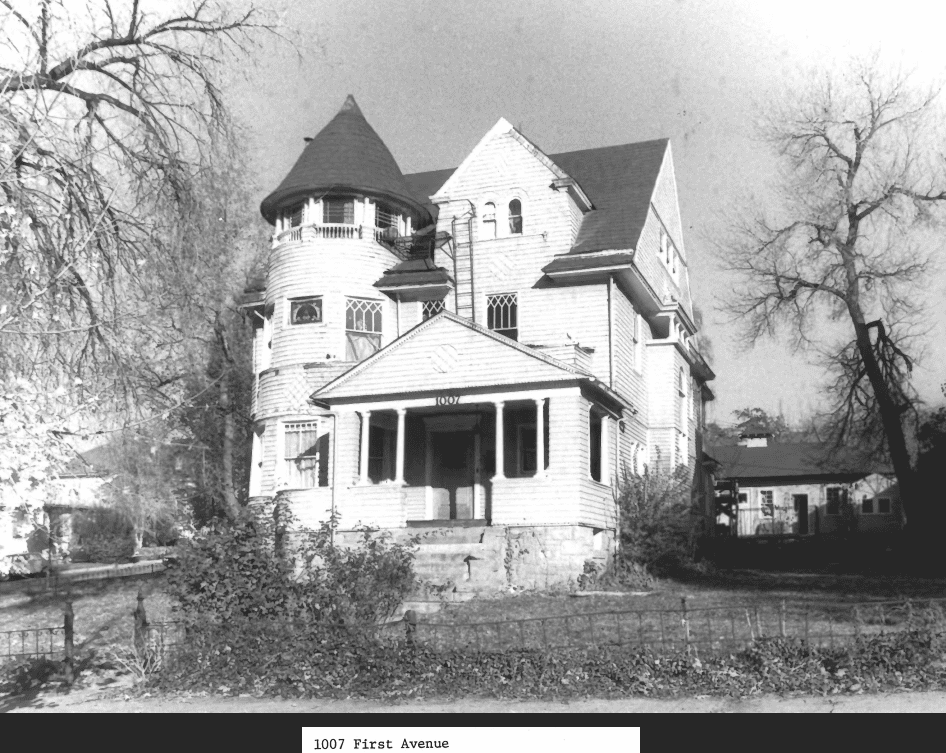

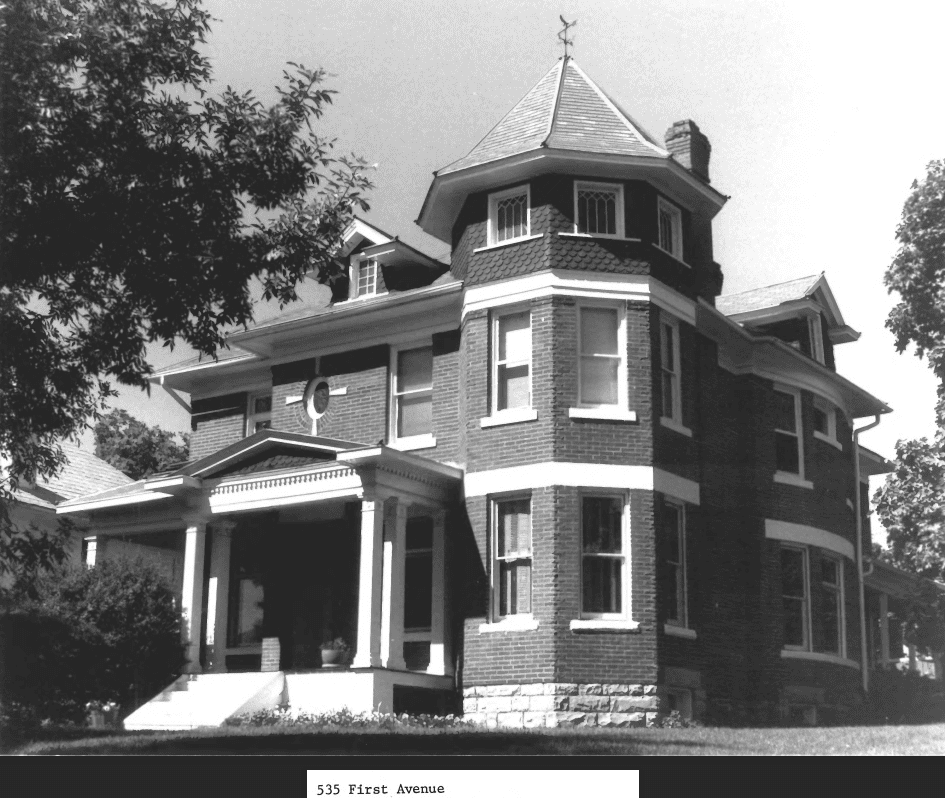

While they account for less than one percent of all residences, the very large, often architect-designed homes in the Eastlake, Queen Anne and Shingle styles, and later the Prairie and Craftsman styles greatly influence the visual character of the Avenues. Some of the state’s best examples of residential architectural styles were built there, including the William Barton house, 231 B Street, (vernacular/Gothic); the Jeremiah Beattie house, 30 J Street, (Eastlake); the David Murdock house, 73 G Street, (Queen Anne); the E.G. Coffin house, 1037 First Avenue, (Queen Anne); the N.H. Beeman house, 1007 First Avenue, (Shingle style); the Vto. Mclntyre house, 257 Seventh Avenue, (Classical Revival); the James Sharp house, 157 D Street, (Craftsman); and the W.E. Ware house, 1184 First Avenue, (Colonial Revival).

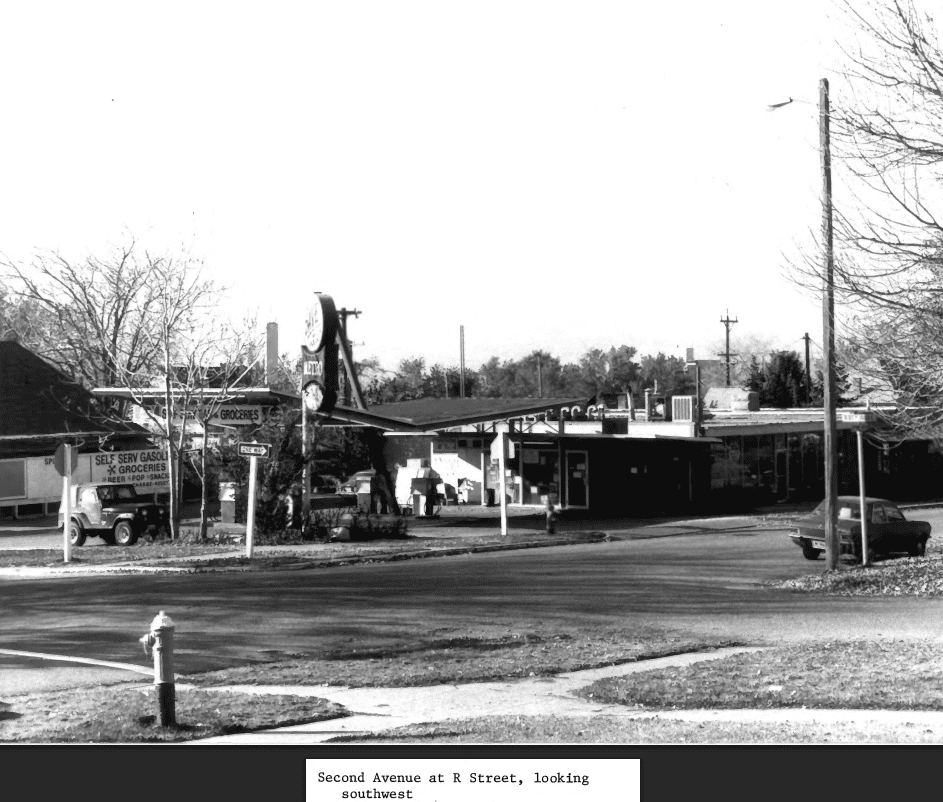

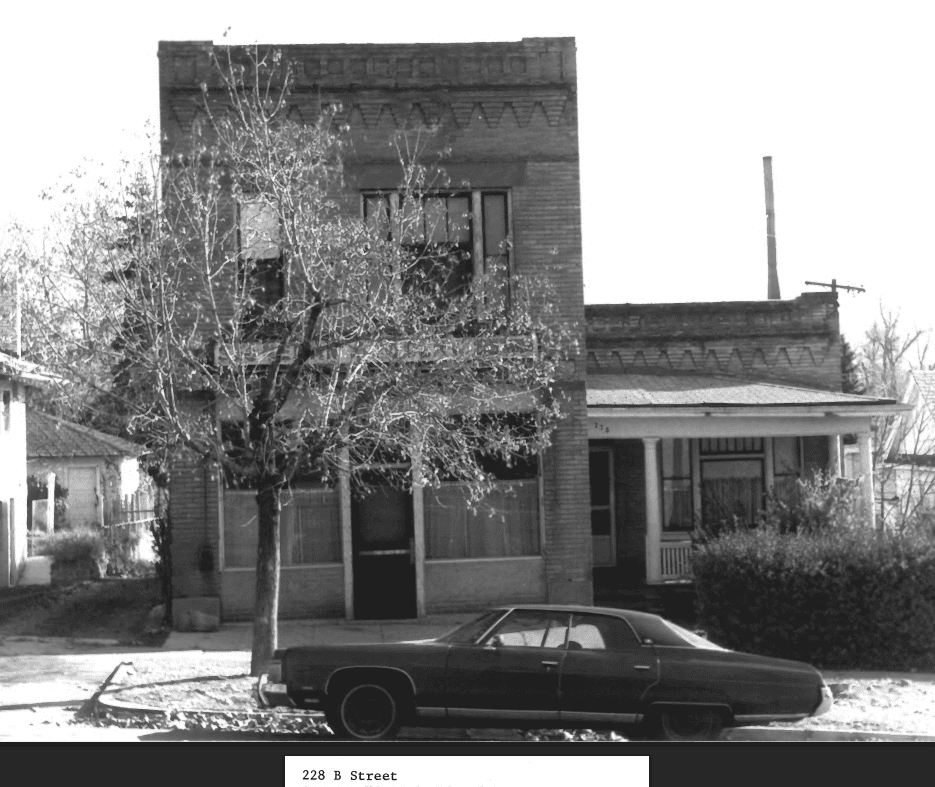

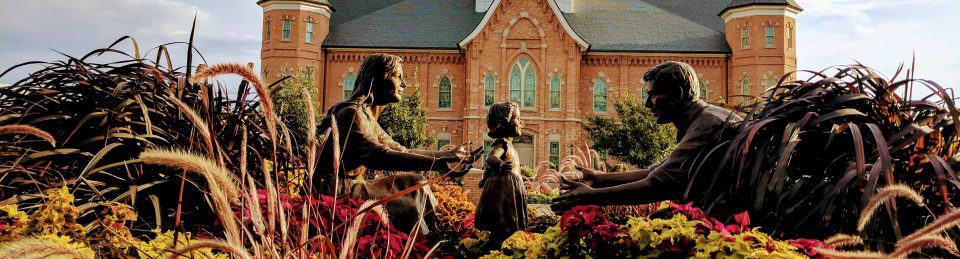

Several significant public and commercial buildings remain on the Avenues. Three churches are important landmarks: the Danish Evangelical Lutheran Church (387 First Avenue), the Twenty-seventh Ward (185 P Street) , and the Twentieth Ward (107 G Street) . The early buildings of Rowland Hall-St. Marks school are the only remaining historic school buildings in the district. There are also a few remaining examples of neighborhood commercial structures.

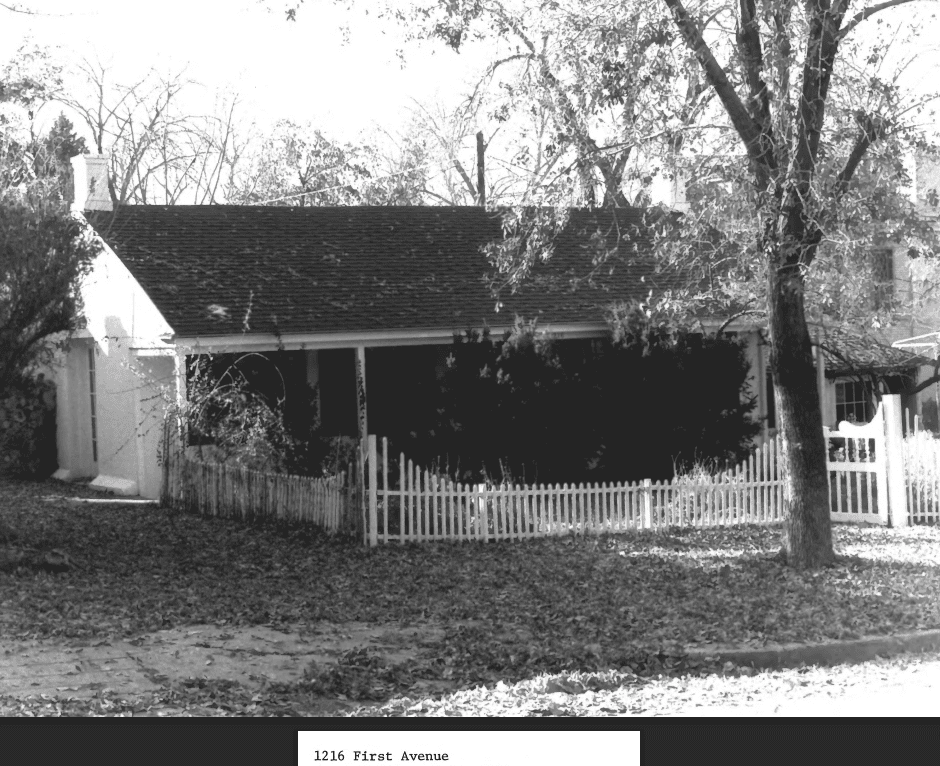

Most of the homes built before 1900, about one third of all the residences, were much plainer than the examples of high style architecture. While incorporating a few elements of various styles – for example, the irregular plans and massing of the Queen Anne style – most Avenues homes lack the elaborate detailing and decorative trim of even the more plain pattern book designs of the period. These houses might more accurately be called “Victorian Builders’ Eclectic. ” While such a phrase lacks the defined characteristic s of traditional stylistic categories of the period, it indicates the casual and general approach to house design reflected in most Avenues homes. While not landmarks themselves, these eclectic designs form a consistent background for the more elaborate examples of pattern book and architect-designed homes.

After about 1900, fashionable neighborhoods were developed to the east and south of the Avenues, around the new campus of the University of Utah (Federal Heights, Gilmer Park, the “Ivy League” streets). The number of very large residences built on the Avenues declined. Some subdivision of larger lots continued, and a number of moderately large, pattern-book bungalows in various styles (especially Prairie Style and Craftsman bungalows) were built. Although the streets on the middle and upper Avenues had been opened for development by the expanded water system, most of the elaborate examples of early twentieth century architecture were built below Seventh Avenue or along the western edge of the Avenues overlooking City Creek Canyon. More modest bungalows filled in the blocks between Fourth and Seventh Avenues, and dominate the area between Seventh and Eleventh Avenues. These early twentieth century homes comprise about one fourth of all the homes in the Avenues. While the styles and floor plans had changed, these homes, like the “Builders’ Eclectic ” before the tum of the century, represented the filtering down of current architectural ideas to local contractors, carpenters and developers.

In the southwest comer of the Avenues, which touches the edge of City Creek Canyon and the central business district, a number of larger apartments, mostly three or four stories, was built. These apartments, built with elements of various early 20th century styles (Mediterranean, Spanish Colonial Revival, Tudor, Art Moderne), comprise almost all of the buildings higher than 2 1/2 stories . They document the twentieth century trend in the Avenues toward rental properties, both the conversion of single family houses and the construction of new apartment buildings.

ASPECTS OF THE DISTRICT’S CHARACTER:

Architectural Styles

Within the Avenues, there are a great number of architectural styles. Often a wide range of styles may be found along one block. These diverse styles are, however, drawn into cohesive patterns because of a similarity of roof pitch, siting, and setback. Diversity is not always the rule. Scattered throughout the district are many pattern book houses. In some instances, these pattern book houses were built side by side by the same builder. This produces a number of duplicates or mirror image variations of the same house.

Density

There is a dense pattern of building in the district. Side yards are usually very small and in some cases almost non-existent. An almost townhouse-like feeling is created on many streets as a result of this dense building pattern and the maintenance of a uniform setback. The tradition of placing the narrow side of the building facing the street reinforces this prevailing pattern.

Setback

Although the construction date of Avenues buildings varies considerably, a fairly uniform setback line was established at an early date in the district. The infill process since that time has tended to hold to that setback line. This helps to establish a definite wall of continuity throughout the district.

Walls of Continuity

Definite walls of continuity are formed along many streets. A number of factors are responsible for creating this aspect of the district: similar setbacks, styles, roof pitches, front porches, retaining walls, fences, landscaping and duplication of the same house type along one street.

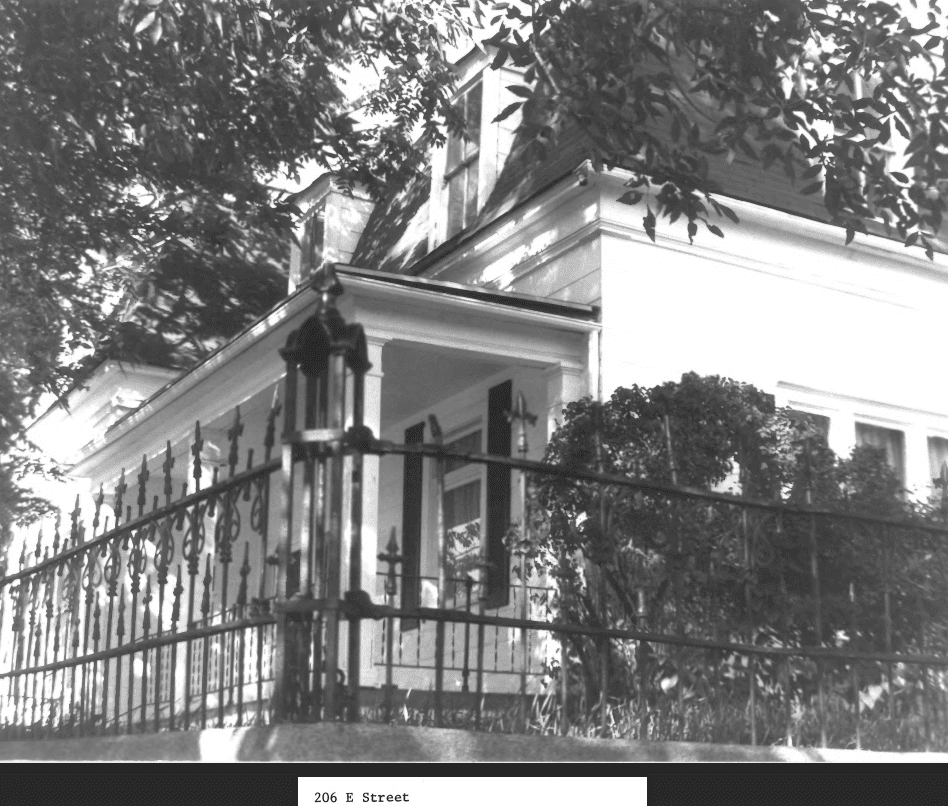

Retaining Walls

On the north, west, and east sides of the streets in the district, retaining walls or terraced yards are often used to create a flat building site. These retaining walls were frequently topped with cast iron fences. The remaining retaining walls serve to place a building on a platform above the street level and delineate the property line.

Front Porches

The front porch is an important aspect of most of the architectural styles to be found in the Avenues district . It is on the front porch that the most decorative and ornate detailing is to be found. The front porch also provides a visual and physical separation from the semi-public space of the front yard. A sense of human scale is created with the single story front porch and a sense of visual relief is imparted through the deep shadow line cast by the front porch. To strip a front porch off an Avenues house or even to remodel the front porch is to destroy much of what imparts character and visual interest to the district.

Fences

At one time, fences at the property line was mandatory in Salt Lake City and the continued presence of original fences or sympathetic replacements is an important part of the Avenues district . Good examples of intact wrought iron fences include 1006 Third Avenue and 1037 First Avenue. Remaining stone walls are now less common; 975 and 983 Third Avenue are examples of red and gray sandstone. Two of the best cobblestone walls are found at 203 Fourth Avenue and 307 M Street.

Landscaping

The district contains a wide variety of mature shade trees. These trees are most frequently found in the planting strip and are maintained by the city. Street trees soften the transition from the paved streets to the semi-public front yards and are important in terms of establishing a wall of continuity through the district.

Unfortunately, the spacing of the street trees in the district is not nearly as close today as in the earlier periods. The density of tree planting and retaining walls helped to establish the character of the district; but some new construction and sparser planting alter s the traditional feeling of the neighborhood.

Most of the street trees now in the Avenues are the result of city tree planting programs. A City ordinance in 1923 authorized specific varieties; maple and plane trees were the most common. In 1932 an ordinance assigned a specific species to each street on the Avenues, with maple and plane again the most frequently used varieties. A few unusual tree species have been identified on the Avenues, including a native big tooth mountain maple at 637 Third Avenue, believe transplanted well before 1900. A European linden brought from England for W.C. Staines before 1869 is located on what are now the grounds of the 20th Ward Chapel on Second Avenue.

Statement of Significance

The area functioned primarily as a middle-class suburb for the downtown commercial district. In its development L.D.S. Church officials, artisans, merchants, mining entrepreneurs, local governmental officials, educators, physicians, attorneys, and laborers all combined to make the Avenues a diverse residential section of Salt Lake City. The Avenues also contained a variety of service-related enterprises. As a whole, the Avenues became an increasingly mixed area, reflecting a general trend. In 1890 about two-thirds of the residents were Mormons, whereas by 1917 it approached 50 percent. By the late nineteenth century, a variety of occupations were represented in the district. These included the following:

- physicians

Dr. Panagestes Kassinikos, 903 1st Ave.

Dr. Alice E. Houghton, 911 3rd Ave.

Dr. Ellis R. Shipp, 711 2nd Ave.

Dr. Samuel H. Allen , 206 8th Ave. - lawyers and judges

William M. McCarty, 1053 3rd Ave. - architects

Walter E. Ware, 1184 1st Ave. - L.D.S. Church Officials

Brigham H. Roberts, 77-79 C St.

Heber J. Grant, Church President from 1918-1945, 201 8th Ave. - educators and politicians

Noble Warrum, 1153 2nd Ave.

Dr. Christian N. Jensen, 1202 4th Ave.

Orson F. Whitney, 764 4th Ave.

Lydia D. Alder, 320 1st Ave.

Heber M. Wells, Governor of Utah, 1896-1904, 182 G St.

George H. Dern, Utah Governor, 1925-1933, and U.S. Secretary of War, 1936-1940, 36 H. St. - musicians, artists, photographers

Anton Pedersen, 509 3rd Ave.

James J. McClellan, 688 1st Ave.

Joseph J. Daynes, 38 D St.

Henry Culmer, 33 C St.

Charles R. Savage, 80 D. St. - merchants

Castleton Brothers, 740 2nd Ave.

J.C. Penney, 371 7th Ave. - clerks and laborers

Orrin Morris, 19 G St.

David A. Coombs, 1216 1st Ave.

Oscar H. Cools, 83 Q. St.

William H. McIntyre, a prominent mining magnate, purchased a mansion at 259 7th Avenue, deviating from the traditional pattern of mining entrepreneurial families locating on Salt Lake’s palatial South Temple Street.

The neighborhood exhibited in the early decades of the twentieth century a trend toward the increase of rental property. This factor, combined with the growth of absentee ownership, led to a gradual deterioration of the area. In recent years the Avenues has experienced a neighborhood revitalization which has led the way for such activity in other Salt Lake City neighborhoods.

HISTORY

Salt Lake City was founded by the Mormons in July, 1847. The main motivations in founding the new city were religious; thus, the city was a clearly defined and well executed planned settlement, patterned after Joseph Smith’s plat for the City of Zion. This “Mormon village” was designed so farmers could live in town and drive to their fields each day for work.

By the 1850s industry began to develop in Salt Lake City, with the crafts and trades predominating. The next two decades saw a rapid growth in industry and manufacturing. With these trends Salt Lake was changing from a village to a city. It was during this critical transitional change that the Avenues district of Salt Lake City developed. The Avenues were established primarily for artisans, tradesmen, common laborers and others who desired to live in proximity to the city. In addition, “the Avenues district is unique in Salt Lake City for having a small grid iron plan platted on rather steep slopes. This plan, which affords comfortable regularity wit h residential scale, was set by the initial survey work on Plat D done in the early 1850s. This survey employed 2-1/2 acre blocks and 82-1/2′ wide streets and was the first platted area of the city to deviate from the original city plan of 10 acre blocks and 132′ wide streets, based on the ‘Plat of the City of Zion.’

“The blocks contained within Plat D were surrounded by a wall of mud and vegetation which Brigham Young had built around three sides of the city. The wall, which was built in 1853 and 1854, was 8.5 miles long and has been called the longest and most ambitious undertaking of any of America’s walled cities.” In the Avenues area the wall ran along Fourth Avenue, then south on “N” Street. By 1860 it was reported that the wall was crumbling away, having not been maintained.

Avenues street names also deviated from the numbered streets in Salt Lake City. Initially, the names were as follows: Fruit St (First Avenue); Garden Street (Second Avenue); Bluff Street (Third Avenue); and Wall Street (Fourth Avenue). The north-south streets were named Walnut (A Street) , Chestnut (B), Pine (C), Spruce (D), Fir (E), Oak (F), Elm (G), Maple (H), Locust (l) Ash (J) Beech (K), Cherry (L), Cedar (M), and Birch (N, the eastern boundary of the City Wall). However, by 1885 the “Avenues” were referred to as First, Second, Third and Fourth Streets, and the north-south streets were lettered, from A Street to V (later Virginia ) Street. This is the only use of lettered streets in Utah. I n 1907, perhaps to avoid confusion with the street names below South Temple (First South, Second South, etc.), the City Commission voted to change the numbered streets to avenues.

“The Avenues district was once called the ‘dry bench’ due to the lack of water. Because of this paucity, the district developed fairly slowly.” Both residential and commercial development in the area followed the availability of water. “Until the 1880s, when a pipeline was run along Summit Street (Sixth Avenue) from Sudbury Mill on City Creek, settlement was primarily limited to the areas below Wall Street (Fourth Avenue). Individual buildings were constructed during this period in the areas above Wall Street but water sources were limited to wells or hauling by pack animals or residents.” In 1860 the Salt Lake City slaughter yards were moved to the area east and south of the City Cemetery (including the southeast corner of the district) to utilize the water from Dry Canyon and Red Butte Canyon, east of the Avenues. This area became known as “Butcherville ” since workers from the slaughter yards settled there to be near their jobs. During the 1880s this section was also used for brickmaking, again, because of the availability of water from Dry Canyon (the same water supply used for the operation of the City Cemetery).

“In 1911, an 18 inch main was built from City Creek to 13th Avenue and “J ” Street. This temporarily solved the water problem for the upper Avenues and allowed rapid development of the area. However, by the mid-1920s, the limit to which water could be pumped wit h existing equipment was reached and construction of residences higher on the slope was postponed awaiting new sources of water supply.”

“Concurrent wit h the development of water supplies for the district was the establishment of a rail system in the district. By the 1890s trolley lines existed on 1st, 3rd, and 6th Avenues; thus, these streets are wider and flatter than the other Avenue streets. ” By 1921 the streetcar system ran along 3rd, 6th, and 9th Avenues.

The residential and occupational patterns of the Avenues illustrate s the evolution of the area. The western portion of the area is located near the L.D.S. Temple. Mormon ecclesiastical leaders, as well as temple workers, have lived in this section of the neighborhood. Various “family patterns” of Avenue home and land ownership have been identified. Important Utah families, such as the Lyons, Romneys, Hansens, Claytons, Brains, Grants, Glades, and Wells maintained strong ties in the Avenues, wit h properties remaining i n family possession. For the most part , these families dealt in real estate.

Ownership records indicate that Avenue homes were built by both men and women. The westeen portion of the district contained various “polygamous houses;” that is , houses built by one man for his several wives. For example, the homes for Henrietta Woolley Simmons and Rachel Emma Simmons, both built in about 1874, are located at 379 and 385 5th Avenue. Both women were wives of Joseph M. Simmons. Widows built homes both for personal use and as rental properties to serve as a source of income. This trend toward rental property would become a prominent one in the Avenues in the twentieth century. Development companies also contributed largely to Avenues growth, especially after 1900. Pattern book houses became much more common. Important among such companies were Salt Lake Security and Trust Company, Modem Home Building Company, and the National Real Estate and Investment Company. In addition, the Heber J. Grant Company, and Taylor, Romney, and Armstrong families built numerous dwellings in the 1910s and 1920s.

The mixed character of Avenues population in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries reflected the changing character of Salt Lake City. With the increased influence of the mining industry in Utah and improved rail transportation, as well as general rising industrial activity, the socio-economic environment shifted away from the city’s earlier agricultural emphasis. In addition, while Avenues residents may not have controlled religious or economic affairs, as may have been the case for residents of South Temple, many were the key functionaries in the businesses whose influences were felt throughout the state.

Commercial activity in the form of service-related enterprises existed in the Avenues. Included were: small neighborhood grocery stores, dry good and sundry stores, barbershops, shoe shops, laundries, and drug stores, as well as the early slaughter yards and brick yards. In 1921 the Avenues rail system proceeded up “B” Street, then east along Sixth and Ninth Avenues and also up “E” Street, and along Third Avenue. This represented further growth on the upper Avenues.

Churches and schools were built in the area to meet the needs of residents. The L.D.S. Church maintained four wards, the Eighteenth (135 A Street, demolished), the Twentieth (107 G Street) , the Twenty-first (680 Second Avenue, demolished) and the Twenty-seventh (185 P Street) . A Danish Evangelical Lutheran Church was built at 387-389 First Avenue in about 1909. Catholic residents worshipped at the Cathedral of the Madeleine on B Street and South Temple. Avenue schools included: Longfellow School (Comer of J and First), Lowell School (E Street and Second Avenue), Rowland Hall-St. Marks (205 First Avenue, National Register), the Eighteenth Ward School (A Street and Second Avenue) and Ensign School (475 F Street). The Groves-L.D.S. Hospital (Eighth Avenue between C and D Streets) was built to serve the entire city, and many hospital personnel lived in the Avenues.

The historical character of the Avenues forms a tie for the district, but its architectural framework provides the necessary visual elements for an effective district. Setbacks, the spacing of buildings, heights, retaining walls, fences, walls of continuity formed along streets, landscaping, and a variety of architectural styles characterize the Avenues district.

In the early portion of the 20th century a trend began in the Avenues toward rental properties, and reached higher proportions in the depression years of the 1930s. Some accounts maintain that by 1963 two-thirds of all Avenues housing were rentals; whereas, the average for Salt Lake City as a whole was about fifty percent. Such a trend, with an increasingly transient population, combined with the move toward absentee ownership which by the 1960s helped to account for the deteriorating character of the area. It was to the advantage of the absentee landlord to allow rental property to deteriorate as property taxes are assessed according to improvements to the structure on the property.

Since the mid-1960s a neighborhood revival has occurred due to the increasing cost of new construction combined with a basic disenchantment with suburban living. New and old residents have joined to seek the revitalization of old residences and preserve the visual and architectural elements that characterize the area. Such a movement has also occurred in other neighborhoods. The Greater Avenues Community Council was organized as an advocacy group attempting to preserve the life style of one of Salt Lake City’s first residential area. The group has been instrumental in the preparation of the Avenues Master Plan and a number of down-zoning fights. Preservation efforts have met with a high degree of success.

Salt Lake City is experiencing a neighborhood revival wit h the Avenues district a principal mover in that direction. A historian who worked on the Avenues survey has written that the Avenues “… continues to be what it has been for nearly a century, an area where people from diverse backgrounds and a variety of income levels can live together.”

The Avenues Historic District contains the following boundary: from State Street and South Temple north to Canyon Road, east between Third and Fourth Avenue to the stairs on 4th Avenue, then north on both sides of A Street to Sixth Avenue, including the west side of A to 9th Avenue: east along the south side of 9th to B Street, then south to the Mclntyre House (259 7th Avenue). From that point the boundary proceeds east along both sides of 7th Avenue excluding a parking terrace next to 259, to N Street, dropping south to include both sides of 4th Avenue to Virginia Street. The district then includes the west side of Virginia south to the north end of 1st Avenue and then follows west between 1st Avenue and South Temple back to the beginning point (following South Temple property lines).

Although the Avenues neighborhood extends from A Street to Virginia Street and from 1st to 11th Avenues, this boundary was chosen based upon an extensive architectural and historical survey. This area was selected primarily because of it s concentration of significant sites , which have been divided into three categories: historical significance, architectural significance , and those significant because of both factors . This boundary has 134 of the 143 identified significant sites, 57 of the 65 architecturally significant sites, 29 of the 29 historically significant buildings, and 43 of those 48 sites significant for both. In addition, it also contains over 90 per cent of the two and two-and-a-half story dwellings, which represents an important visual feature of the character of the Avenues.

The boundary includes a condominium intrusion at Canyon Road and 2nd Avenue because this corner was considered an integral geographical part of the Avenues; and eliminating this intrusion but including two contributory houses on the northwest side would create a needless and complex irregularity in the boundary. Another factor in the determination of the boundary was the 1870 “Birds Eye View of Salt Lake City, ” by Augustus Koch, which clearly showed 7th Avenue as the uppermost point of Avenues settlement.

Avenues development closely followed the availability of water. Until the 1880s when a pipeline was run along Sixth Avenue, settlement was primarily limited to Fourth Avenue. In 1911 a water main was constructed along Thirteenth Avenue to J Street, which allowed development in the upper Avenues. This factor contributed to further expansion northward, especially evident in the creation of a new school. Ensign School (475 F Street ) in 1912, and a new LDS Ward, the Ensign Ward (Ninth Avenue and D Street), 1913, to serve the increasing population above Seventh Avenue. Together, these factors clearly illustrated the geographical development of the Avenues area. The northwest section of the historic district above Seventh Avenue was included because of the “family patterns” of ownership, especially evident in the block between A and B Streets and Eighth and Ninth Avenues and because of the existence in the vicinity of the palatial Mclntyre House.

a

Pingback: 985 1st Avenue | JacobBarlow.com

Pingback: Salt Lake by Address (north) | JacobBarlow.com

Pingback: Joseph L. Rawlins House | JacobBarlow.com

Pingback: 925 1st Avenue | JacobBarlow.com

Pingback: 935 3rd Avenue | JacobBarlow.com

Pingback: 1082 4th Avenue | JacobBarlow.com

Pingback: 117 C Street | JacobBarlow.com

Pingback: 224 A Street | JacobBarlow.com

Pingback: 212 E Fifth Avenue | JacobBarlow.com

Pingback: 1055 2nd Avenue | JacobBarlow.com

Pingback: 823 2nd Avenue | JacobBarlow.com

Pingback: 776 2nd Avenue | JacobBarlow.com

Pingback: Cathedral of the Madeleine | JacobBarlow.com

Pingback: Thomas Kearns Mansion and Carriage House | JacobBarlow.com