Hole-in-the-Rock Trail

The Hole-in-the-Rock Trail is significant because of its importance in the Mormon exploration and settlement of Utah and the San Juan country of the southwest. The trail reflects the commitment and courage of a people who were convinced they were a part of a divinely inspired and directed mission. The Hole-in-the-Rock Trail is an important symbol of the Mormon colonization effort in the intermountain west during the last half of the nineteenth century. Although the settlement ..cane at a relatively late date in this history, the descent through the Hole-in-the-Rock and the persistence in constructing a road through one of the most rugged and isolated sections of the United States illustrates the fortitude of the American pioneer and serves as a vivid lesson to other generations of the importance of commitment and cooperation in meeting the challenges of their day.

Hole-in-the-Rock Trail is in Garfield, Kane and San Juan Counties in Utah and was added to the National Historic Register (#82004792) on August 9, 1982.

The Hole-in-the-Rock Trail is significant as one of the last remaining and best preserved pioneer trails in Utah and the United States. While almost all routes used by pioneers in Utah have evolved into major highways, the Hole-in-the-Rock Trail, except for a few sections, has not. Because of the lack of development along the trail, it has, in many places, remained unchanged. Original cribbing, cuts blasted out by the road builders, stumps of trees cut to allow passage through the cedar forests, traces across the mesas and along the valley floors, important natural landmarks and Indian ruins remain unchanged since they were described by the travelers. In a few places, parts of original wagons are found along the trail.

The construction techniques and engineering of the pioneer road which are still visible illustrate the needs and limitations of a different form of transportation than we know today.

The Hole-in-the-Rock Trail is also unique in that it was not used very much after it was constructed. Most trails and roads are significant because of the heavy use they received and the role they playsd in the history of transportation. The Hole-in-the-Rock Trail, in contrast, is important primarily for its construction.

The settlement of the San Juan region by Mormons in 1880 was a continuation of the practice initiated with the arrival of the first Mormon pioneers in Utah in 1847 and which lasted more than fifty years into the twentieth century. The colonizing effort by Mormons in the intermountain west led to the establishment of nearly four hundred communities found as far north as Canada and into Mexico on the south. While each of these settlement efforts required, in some measure, the sacrifice, commitment and pioneering ability of Utah’s first Mormon settlers, the efforts of those men and women who built and crossed the Hole-in-the-Rock Trail, loom, in retrospect, larger than any other pioneering endeavor in Utah and perhaps the entire west. As the historian of the Hole-in-the-Rock expedition, David E. Miller, noted it was truly “An Epic in the Colonization of the Great American West.”

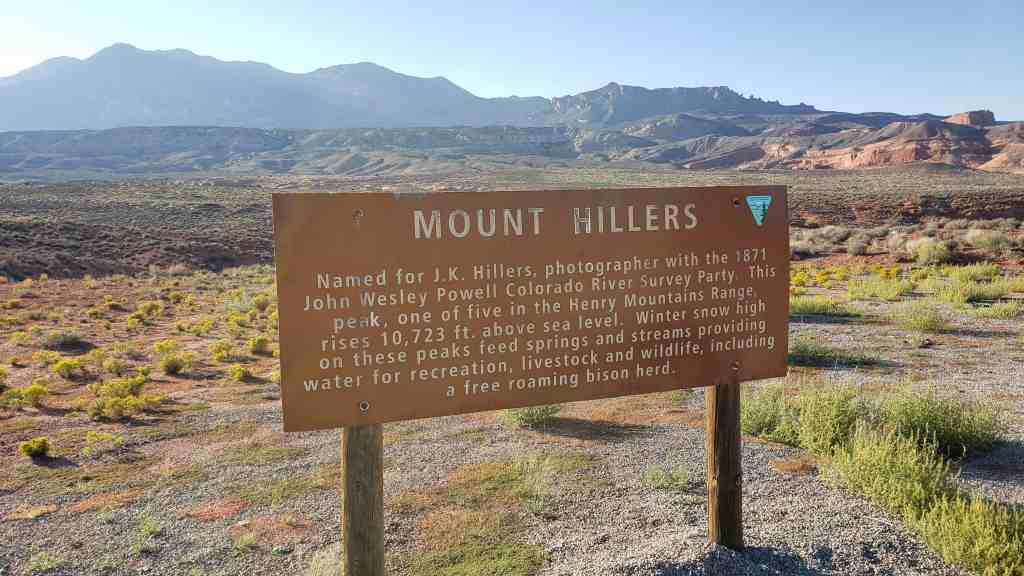

The San Juan region was, and is still, one of the most isolated parts of the United States. The country is extremely rough and broken. The canyons of the Colorado River and San Juan River and their tributaries are usually characterized by sheer walled cliffs several hundred feet high, while the surrounding mesas, hills and washes with their bone jarring slick rock, cedar forests and sand presented their own obstacles to transportation. In addition, by 1880 the San Juan Region was the last area in Utah of occupation by a large number of Indians as the San Juan River was something of a natural meeting area for Navajos, Utes and Paiutes who occupied the region.

Given the isolation from other Mormon settlements, the closest was Escalante about two hundred miles away, the ruggedness of the country, the questionable agricultural potential of the region, the availability of more assessible virgin agricultural land in other areas, and the threat of Indian hostilities, it is understandable why the settlement of the San Juan area came in the twilight of the Mormon settlement effort. That the settlement was not delayed longer than 1880 was due to the need to cultivate better relations with the Indians, to insure Mormon control of the area thereby increasing the security of Mormon settlements to the west and providing a springboard for future Mormon settlements to the east, south and north.

Despite an avowed Church policy to feed rather than fight the Indians, as Mormon settlements pushed into southern Utah and Northern Arizona, the roving bands of Navajos and Paiutes found the flocks and herds of the Mormon settlers an easily available and irresistible booty. As David E. Miller notes:

Being well acquainted with all possible crossings of the Colorado, small parties of Indians often raided the outlying settlements, drove off stock and disappeared into secret hideouts southeast of the river, beyond the reach of their pursuers. At times this plundering assumed rather important proportions. One writer states that in 1867 a herd of soma twelve hundred stolen animals was pushed across the Colorado at the Crossing of the Fathers and that in one year more than a million dollars’ worth of horses, cattle and sheep was looted from the impoverished Utah frontier…

By the mid-1870s the San Juan area of southeastern Utah had for some time been known as a refuge for lawless men, white as well as red; it was literally an outlaw hideout, as the settlers would soon learn. A colony there would act as a buffer to absorb any possible hostilities far short of the rest of settled Utah. (Miller, Hole-in-the-Rock pp. 7-8).

Also of great concern to Church leaders was the occupation of all usable farm and grazing land, especially as non-Mormons threatened to acquire the land. The San Juan Region was also felt to provide a more satisfactory home for converts from the Southern states who found the winters too cold yet, according to church leaders, needed the pioneer experience to get “… a good foundation temporally and spiritually.” (John Morgan to Erastus Snow, May 9, 1978, quoted in Miller, Hole-in-the-Rock p. 6.).

Finally members of the Hole-in-the-Rock expedition were convinced that they were carrying out the work of the Lord. As one member of the expedition wrote in later years:

My purpose in this humble effort in writing about it (the Hole-in-the-Rock trek) is to convince my children and my descendants of the fact that this San Juan Mission was planned, and has been carried on thus far, by prophets of the Lord, and that the people engaged in it have been blessed and preserved by the power of the Lord according to their faith and obedience to the counsels of their leaders. No plainer case of the truth of this manifestation of the power of the lord has ever been shown in ancient or in modern times. (Kumen Jones quoted in Miller, Hole-in-the-Rock p.13)

Plans for a colonizing mission to San Juan were announced at the quarterly conference of the Parowan Stake held December 28 and 29, 1878. Although the specific location of the settlement had not been selected, people were issued calls to participate in the endeavor. For many this meant giving up comfortable homes in the older settlements of Parowan, Cedar City, Paragonah, Panguitch, and other communities. While those called were not compelled to go, many firmly believed that the call was divinely inspired and wherever church authorities directed, they would go.

In the spring of 1879 an exploring party consisting of 26 men, two women and eight children under the leader ship of Silas S. Smith, left to explore the trail to the San Juan River and select a permanent settlement location. Traveling southeast into Arizona they crossed the Colorado River at Lee’s Ferry and continued on to Moenkopi where they turned northeast and traveling through Navajo country recrossed the Utah-Arizona border and made their way to Montezuma on the San Juan River. Here they spent two and one half months exploring the area, building a dam, digging irrigation ditches and building a few houses before returning to the settlements for their families and equipment.

The trail from Moencopi to the San Juan River had proven very dry, and severe Indian threats led to the abandonment of this route as a practical way to the San Juan Region from the Southern Utah settlements. The exploring party returned to their homes by traveling north past the future site of Monticello and to the Old Spanish Trail at the south end of the LaSal Mountains. They followed the Old Spanish Tail west to the crossing of the Colorado River at present-day Moab, the Green River at present-day Green River, through Castle Valley, and down Salina Canyon to the Sevier Valley then south back to Parowan. In retrospect this northern route along the Spanish Trail would have been the most practical. However the circuitous route covered a distance of more than five hundred miles whereas a direct route would be less than half the distance.

To those called to settle the San Juan region, the report that a direct route from Escalante to the San Juan River had been found must have been taken as evidence of God’s help in the endeavor. During the summer of 1879 Andrew P. Schow and Reuben Collett of Escalante, in response to a request by Silas S. Smith the leader of the San Juan mission, explored east from Escalante with a two wheeled cart carrying a wagon box boat to the Colorado River. After crossing the river they returned to Parowan with a favorable report of the trail. Silas Smith, who was good friends with the men, was anxious to avoid both the southern and northern routes of the exploring expedition and on the strength of the Schow-Collett report, announced in September 1879 that the Expedition would proceed to the San Juan via the Escalante route.

Shortly after the announcement, members of the expedition began their journey to Escalante then on to Forty-Mile Spring which was the first major camp site and general point of rendezvous for the groups coming from different communities.

From Forty-Mile Spring exploring parties were sent out to reconoiter the trail east of the river. Despite negative reports of the feasibility of constructing a wagon road east of the river, Silas S. Smith was left with little choice but to push on ahead since the winter snows in the Escalante mountains blocked the return to their former homes. The decision to push on was welcomed in the camp and confident that the decision was divinely inspired a spirit of optimism and good will prevailed as the expedition began its push to the Colorado River and the descent through the Hole-in-the-Rock. This section of the trail was not without difficulty. Miller writes:

From a road builder’s point of view, the sixty-five mile region between the town of Escalante and the Colorado River at Hole-in-the-Rock grows progressively worse as one proceeds southward into the desert. The San Juan pioneers had experienced considerable difficulty on the first forty miles of the road, but the remaining fifteen miles they found several times more difficult. This country is very deceptive: What appears to be a fairly level plain, lying between the Straight Cliffs of Fifty-Mile Mountain and the Escalante River, is literally almost straight-walled gorges and canyons which head in the Kaiparowits and cut deeper and deeper as they extend eastward toward the Escalante River gorge….

From Forty-Mile Spring southward the washes, gulches, and canyons not only become progressively more numerous, but also much more difficult to cross. If the San Juan pioneers had merely succeeded in building a wagon road through that part of the country—to Fifty-Mile Spring—and then returned to the settlements, their achievement would have been outstanding. But this was really easy terrain to cross compared to what lay ahead. (Miller, Hole-in-the-Rock pp. 70-71).

By early December 1879 the expedition had arrived at the Hole-in-the-Rock where they would spend the next eight weeks on three major road building tasks: the notch itself; the road from the base of the cliffs to the Colorado River; and the dugway out of the river gorge to the east which had to be cut from the Solid Rock Wall.

Before work started down through the Hole-in-the-Rock, the cleft was nothing more than a very narrow crack—described as “…too narrow to allow passage for man or beast.” (Miller, Hole-in-the-Rock p. 101).

Because of the shortage of blasting powder and tools and the limited working space at the top of the Hole, the men were divided into three crews and work proceeded simultaneously on all three projects. Those working at the top of the Hole had to be lowered over the cliff with ropes until a suitable grade had been cut. Jens Nielson, Benjamin Perk ins and Hyrum Perk ins were in charge of the blasting. THe Perkins brothers became proficient in the use of blasting powder in the coal mines of Wales before emigrating to the United States.

The descent by wagon through the Hole required rough-locking the wheels and attaching long ropes to the wagon so that a dozen or more men could hang on and help slow the descent of the wagon. Women and children walked down through the Hole and were forced to slide down the forty feet at the top because it was so steep they could not walk. Writing to her parents Elizabeth Morris Decker gave this contemporary account of the descent to the river:

It is about a mile from the top down to the river and it is almost straight down, the cliffs on each side are five hundred ft. high and there is just room enough for a wagon to go down. It nearly scared me to death. The first wagon I saw go down they put the brake on and rough locked the hind wheels and had a big rope fastened to the wagon and about ten men holding back on it and then they went down like they would smash everything. I’ll never forget that day. When we was walking down Willie looked back and cried and asked me how we would ever get home, (quoted in Miller, Hole-in-the-Rock p. 116).

Despite the dangerous descent there was no major tragedy—no animals were killed and no wagons were tipped over or seriously damaged.

While the road was being cut through the Hole-in-the-Rock, four scouts were sent ahead to explore the rest of the trail to Montezuma. Setting out on December 17th the scouts readied the present site of Bluff December 28th. Despite an extremely difficult trek, marked by snowy cold weather and no food for the last four days, the scouts did locate the trail at the San Juan River and returned to the Expedition at the Hole-in-the-Rock with their report on January 14, 1880.

Although the descent through the Hole-in-the-Rock would symbolize the courage and commitment of the San Juan pioneers once across the Colorado River they would be tested at several other locations including Cottonwood Hill, The Chute, Clay Hill Pass, and San Juan Hill. This journey of 125 miles took over two months with much of the time spent in road construction.

The last great test was only a few miles from their final destination at San Juan Hill. Because of the sheer cliffs on Comb Ridge, the expedition was forced to follow Comb Wash to its junction with the San Juan River. With no choice but to go up onto Comb Ridge the pioneers spent several days building a road up the steep slope of San Juan Hill. The ascent up San Juan Hill seemed, in many ways, more difficult than the descent through the Hole-in-the-Rock. Charles Redd, whose father L.H. Redd was a member of the original expedition, wrote the following account of the climb up San Juan Hill:

Aside from the Hole-in-the-Rack, itself, this was the steepest crossing on the journey. Here again seven span of horses were used, so that when some of the horses were on their knees, fighting to get up to find a foothold, the still-erect horses could plunge upward against the sharp grade. On the worst slopes the men were forced to beat their jaded animals into giving all they had. After several pulls, rests, and pulls, many of the horses took to spasms and near convulsions, so exhausted were they. By the tine irost of the outfits were across, the worst stretches could easily be identified by the dried blood and matted hair from the forelegs of the struggling teams. My father (L.H. Redd, Jr) was a strong man, and reluctant to display emotion; but whenever in later years the full pathos of San Juan Hill was recalled either by himself or by someone else, the memory of such bitter struggles was too much for him and he wept. (Miller, Hole-in-the-Rock pp. 139-140).

Once on top of Comb Ridge the road, with the exception of constructing dugways into and out of Butler Wash, was relatively easy on to the San Juan River. However, the expedition stopped eighteen miles short of the intended destination of Montezuma and named the site of their new settlement Bluff.

Although he Hole-in-the-Rock Trail did not become a major highway, it was used on occasion until the Hall’s Crossing route was opened several years later. However, much of the trail, with the exception of the difficult stretch from Lake Canyon to the Hole-in-the-Rock, was used as part of the Hall’s Crossing route. Jeep expeditions and hikers still follow the trail and major commemoration activities are planned for the Centennial Anniversary of the Hole-in-the-Rock Expedition in 1980.