Tags

Central Overland Stage, historic, Historic Markers, Overland Trail, Pony Express, SUP, UPTLA, utah

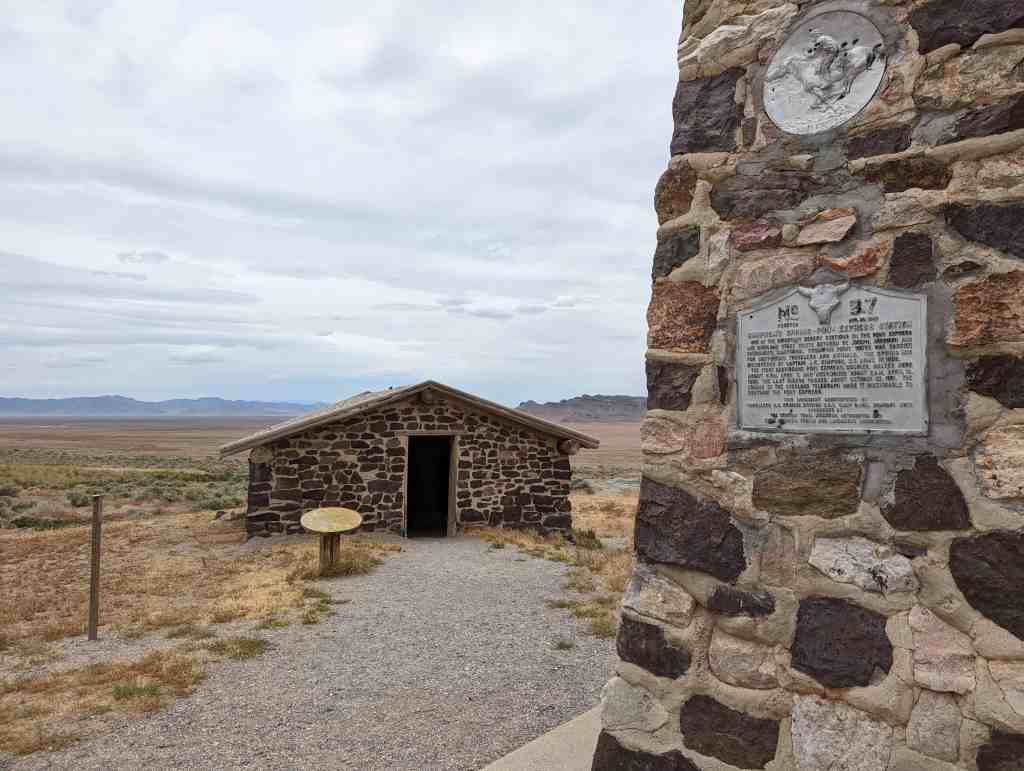

Rush Valley Station

Pony Express – 1860-61

St. Joseph, Missouri – Sacramento, California

Also Overland Stage & Freight Route 1858-1868

Note: The above is a replica of the marker placed c. 1947. However, no records prior to 1862 show a station here. This includes the 1861 Pony Express schedule. In 1862, this new station was built by the Central Overland Stage & Freight and used by others.

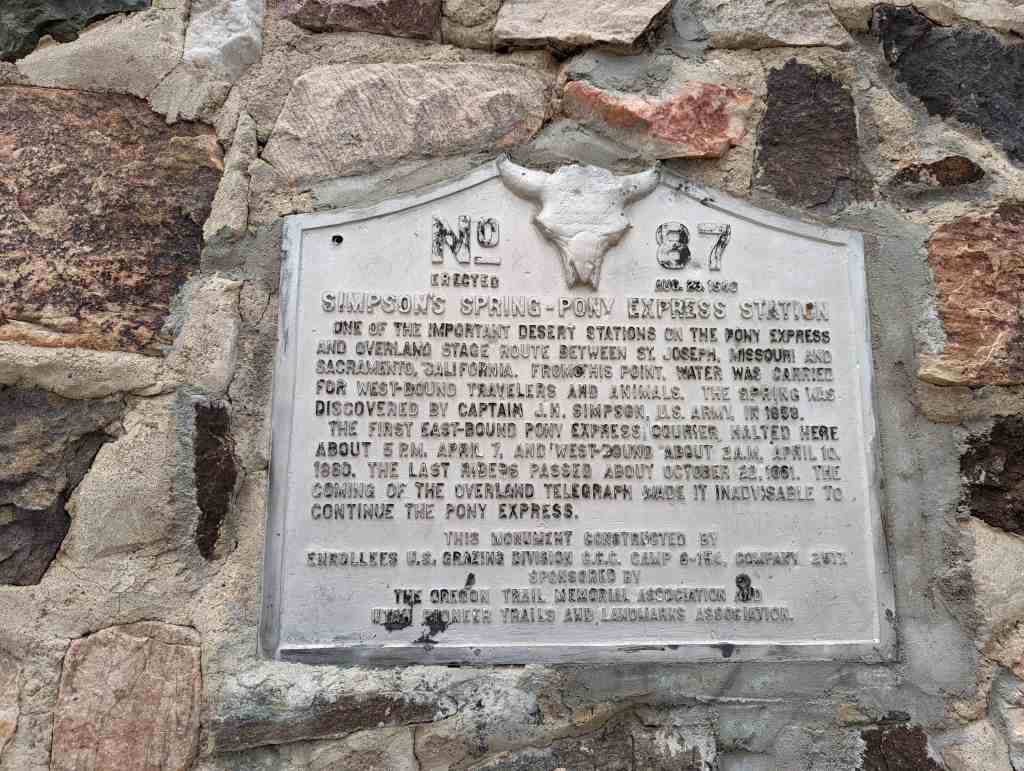

This monument was constructed by enrollees, U. S. Grazing Division, C. C. C. Camp G-154, Company 2517 in 1941 and sponsored by the Utah Pioneer Trails and Landmarks Association (#98 of their monuments) it was later adopted by the Sons of Utah Pioneers (#240 of their monuments) and rededicated in 2017.

Related: